New brain implant can decode a person's 'inner monologue'

A new brain-computer interface can decode a person's inner speech, which could help people with paralysis communicate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

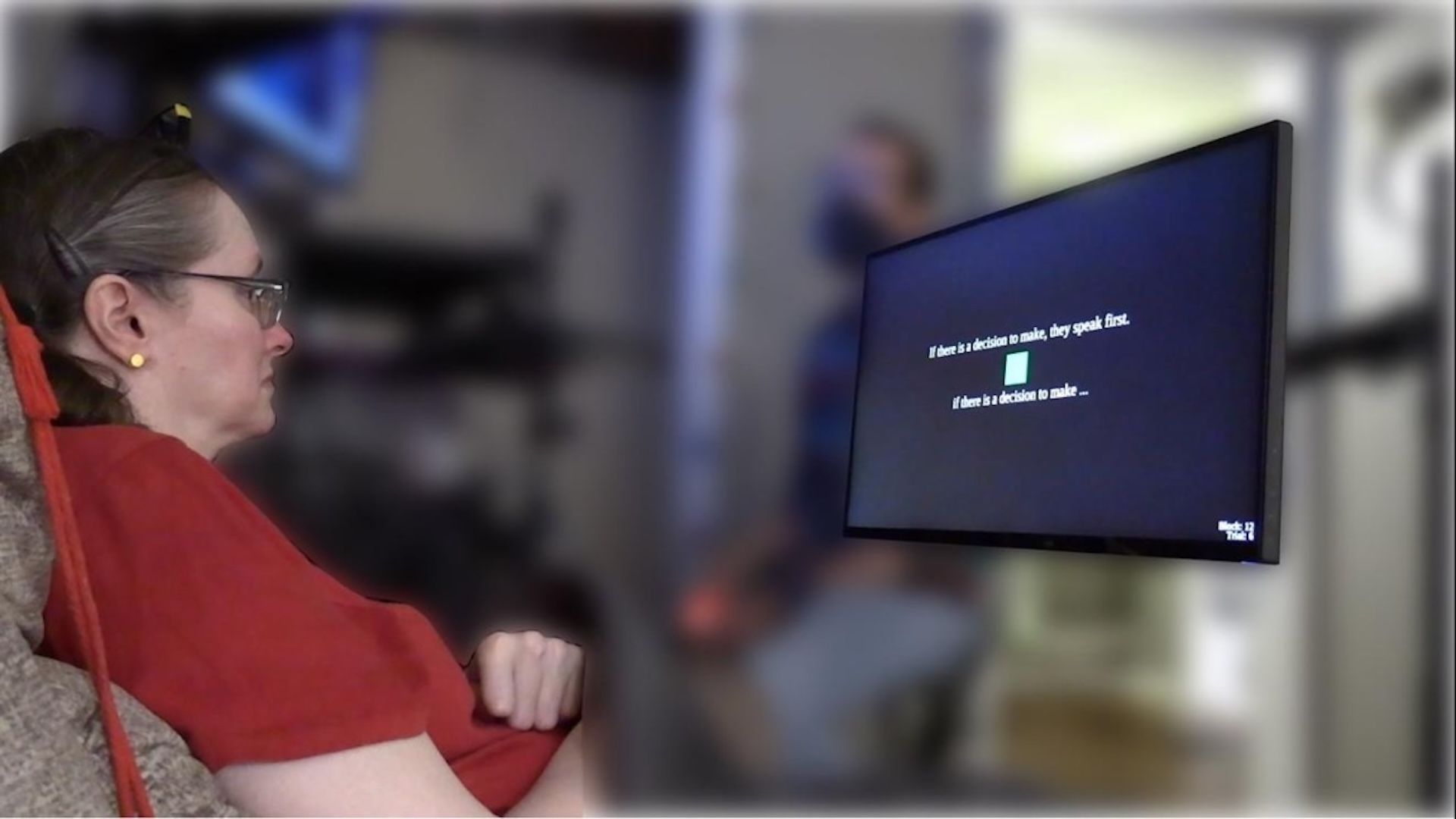

Scientists have developed a brain-computer interface that can capture and decode a person's inner monologue.

The results could help people who are unable to speak communicate more easily with others. Unlike some previous systems, the new brain-computer interface does not require people to attempt to physically speak. Instead, they just have to think what they want to say.

"This is the first time we've managed to understand what brain activity looks like when you just think about speaking," study co-author Erin Kunz, an electrical engineer at Stanford University, said in a statement. "For people with severe speech and motor impairments, [brain-computer interfaces] capable of decoding inner speech could help them communicate much more easily and more naturally."

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) allow people who are paralyzed to use their thoughts to control assistive devices, such as prosthetic hands, or to communicate with others. Some systems involve implanting electrodes in a person's brain, while others use MRI to observe brain activity and relate it to thoughts or actions.

But many BCIs that help people communicate require a person to physically attempt to speak in order to interpret what they want to say. This process can be tiring for people who have limited muscle control. Researchers in the new study wondered if they could instead decode inner speech.

In the new study, published Aug. 14 in the journal Cell, Kunz and her colleagues worked with four people who were paralyzed by either a stroke or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a degenerative disease that affects the nerve cells that help control muscles. The participants had electrodes implanted in their brains as part of a clinical trial for controlling assistive devices with thoughts. The researchers trained artificial intelligence models to decode inner speech and attempted speech from electrical signals picked up by the electrodes in the participants' brains.

The models decoded sentences that participants internally "spoke" in their minds with up to 74% accuracy, the team found. They also picked up on a person's natural inner speech during tasks that required it, such as remembering the order of a series of arrows pointing in different directions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Inner speech and attempted speech produced similar patterns of brain activity in the brain's motor cortex, which controls movement, but inner speech produced weaker activity overall.

One ethical dilemma with BCIs is that they could potentially decode people's private thoughts rather than what they intended to say aloud. The differences in brain signals between attempted and inner speech suggest that future brain-computer interfaces could be trained to ignore inner speech entirely, study co-author Frank Willett, an assistant professor of neurosurgery at Stanford, said in the statement.

As an additional safeguard against the current system unintentionally decoding a person's private inner speech, the team developed a password-protected BCI. Participants could use attempted speech to communicate at any time, but the interface started decoding inner speech only after they spoke the passphrase "chitty chitty bang bang" in their minds.

Though the BCI wasn't able to decode complete sentences when a person wasn't explicitly thinking in words, advanced devices may be able to do so in the future, the researchers wrote in the study.

"The future of BCIs is bright," Willett said in the statement. "This work gives real hope that speech BCIs can one day restore communication that is as fluent, natural, and comfortable as conversational speech."

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus