Snakes' mind-bending 'heat vision' inspires scientists to build a 4K imaging system that could one day fit into your smartphone

The human eye can only detect wavelengths in the visible light range, but a new imaging system will let us "see" infrared radiation using smartphones.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists in China have developed a first-of-its-kind artificial imaging system inspired by snakes that are able to "see" heat coming off their prey in total darkness. The sensor captures ultra-high-resolution infrared (IR) images in 4K resolution (3,840 × 2,160 pixels) — matching the image quality of the iPhone 17 Pro's camera.

Any object with a temperature above absolute zero (-460 degrees Fahrenheit or -273 degrees Celsius) emits some electromagnetic radiation. For normal body heat, this has a wavelength in the IR range. The human eye can only pick up shorter wavelengths that are in the visible light range.

Snakes can also see visible light — but some species, such as pit vipers (Crotalinae), also have a special heat-sensing organ just next to their nostrils that allows them to visualize longer wavelength IR radiation.

Article continues belowIt is called a "pit" organ as it comprises a hollow chamber with a thin membrane suspended across it. When IR waves heat specific areas of the membrane, a thermal "image" is sent to the brain via the attached nerves.

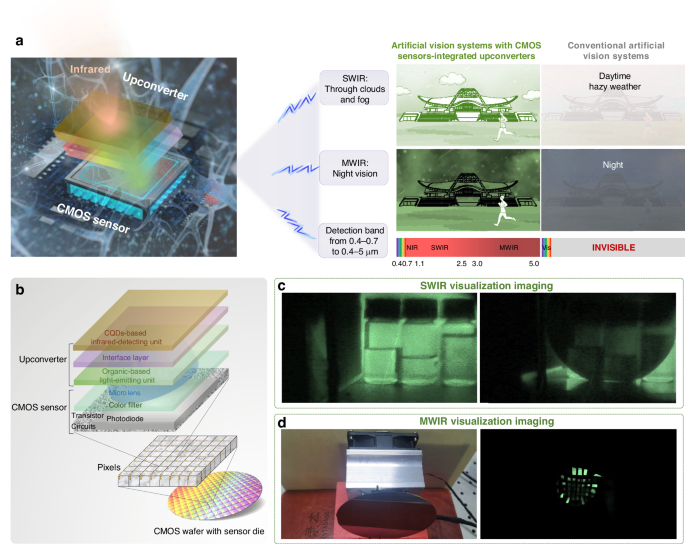

Scientists from the Beijing Institute of Technology used this concept to create their own IR detecting system. They stacked layers of different materials on an 8-inch disc, through which the radiation passes until it manifests as a high-quality image visible to the human eye. The system was outlined in a study published Aug. 20 in the Nature journal Light: Science & Applications.

The first layer of the imaging system is an IR sensing layer, formed of so-called "colloidal quantum dots" — tiny nanoparticles made from mercury and tellurium atoms that release electrical charges when they absorb IR radiation. The charges then travel through several noise-reducing layers to an organic light-emitting diode (LED) layer known as the "upconverter."

Here, the electrons meet "holes" (absences of electrons) and release energy, which phosphorescent molecules convert to green, visible light. Finally, the visible light meets the "complementary metal oxide semiconductor" (CMOS) layer and is converted into an image.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

IR vision in future smartphones and cameras

This is the first system that can turn short and mid-wave IR (wavelengths of 1.1 to 5 micrometers) into an ultra-high-resolution image at room temperature. Because the CMOS sensor is directly on top of the upconverter, weaker IR signals are captured before noise can drown them out. In other systems, where the CMOS and upconverter are separated, costly cryogenic cooling is required to prevent noise buildup as the signals travel between them.

Being able to see IR radiation effectively extends the range of wavelengths visible to humans by more than 14 times. A camera fitted with the sensor’s technology will be able to detect warm objects in conditions with low light, such as in fog, through smoke or at night.

"The extended artificial vision into infrared range could operate in all weather, whether day or night, regardless of extreme weather, and be of use in new fields such as industry inspection, food safety, gas sensing, agricultural science, and autonomous driving,” the researchers wrote in the study.

They added that tens of millions of pixels using their system "could be achieved at an extremely low cost," making the technology more feasible for consumer cameras and smartphones in the future.

Indeed, these devices already use standard silicon CMOS sensors upon which the layers could be attached.

Fiona Jackson is a freelance writer and editor primarily covering science and technology. She has worked as a reporter on the science desk at MailOnline, and also covered enterprise tech news for TechRepublic, eWEEK, and TechHQ.

Fiona cut her teeth writing human interest stories for global news outlets at the press agency SWNS. She has a Master's degree in Chemistry, an NCTJ Diploma and a cocker spaniel named Sully, who she lives with in Bristol, UK.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus