That was the week in science: Farewell comet 3I/ATLAS | Starlink tumbles from orbit | AI’s giant carbon footprint

Friday, Dec. 19, 2025: Your daily feed of the biggest discoveries and breakthroughs making headlines.

Here's the biggest science news you need to know.

- Comet 3I/ATLAS is zooming away from Earth after making its closest approach last night.

- A starlink satellite is tumbling from space after shattering in orbit.

- AI systems had a carbon footprint equal to New York City, and consumed similar quantities of water to the annual global consumption of bottled water, in 2025, new study claims.

Latest science news

Little Foot

Good morning, science fans! Thank you for your patience last week while we worked through some technical issues. I'm pleased to report that the science news blog is back!

We're kicking off this week's blog coverage with a story about human evolution. A team of researchers believes that the hominin fossil "Little Foot" is an unknown human ancestor, the Guardian reports.

Little Foot is a near-complete Australopithecus skeleton — the most complete ever discovered — from South Africa. Researchers first unveiled the small ancient human in 2017, but precisely where it sits on our family tree has been the subject of scientific debate.

Some have proposed that Little Foot is a previously unknown species and should be given the name Australopithecus prometheus. However, A. prometheus is a recycled name that was initially meant for another South African fossil discovered in 1948, but fell out of favour after researchers decided that the fossil was likely from the known species Australopithecus africanus. Another possibility was that Little Foot was also A. africanus.

The new claims derive from a study published last month in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology. Here, the research team argues that neither A. prometheus nor A. africanus is an appropriate classification for Little Foot.

The classification of human fossils is often contested, so I'm keen to see how other anthropologists react to the new study and will follow up with more information as it emerges.

Live Science weekend news roundup

Here are some of the best Live Science stories from the weekend:

- Scientists finally sequence the vampire squid's huge genome, revealing secrets of the 'living fossil'

- 2,000-year-old shipwreck may be Egyptian 'pleasure barge' from last dynasty of pharaohs

- Brutal lion attack 6,200 years ago severely injured teenager — but somehow he survived, skeleton found in Bulgaria reveals

Geminids peak

Did you catch any meteors this weekend? The Geminid meteor shower peaked on Saturday night and Sunday morning in a near-moonless sky, making it perfect conditions for capturing the spectacle on camera.

The Geminids represent the most prolific meteor shower of the year. While the shower has been ongoing since Dec. 4, the best time to see its meteors was supposed to be overnight on Saturday through Sunday.

I didn't see any because I was busy and unwilling to brave the cold. If like me you missed them too, we've still got a few more days to brave the elements — the Geminids will remain active until Dec. 20. I'll also pull together a little gallery of some of the best images from the Geminids' peak to mark the event.

If you want to learn more about the Geminids, check out our 2025 Geminids meteor shower guide by skywatching expert Jamie Carter.

Geminid meteor shower gallery

Here are some pretty pictures from the Geminids' weekend peak:

The Geminids above Yosemite National Park in California.

A meteor zooms across the night sky above Ulanqab, Inner Mongolia, in China.

Back to Yosemite National Park for another striking meteor snap.

The Geminids above Yamdrok Lake in Tibet, China.

Here, a meteor appears as a horizontal dash across the night sky. This is the third photo taken by Tayfun Coskun at Yosemite National Park.

All eyes on 3I/ATLAS

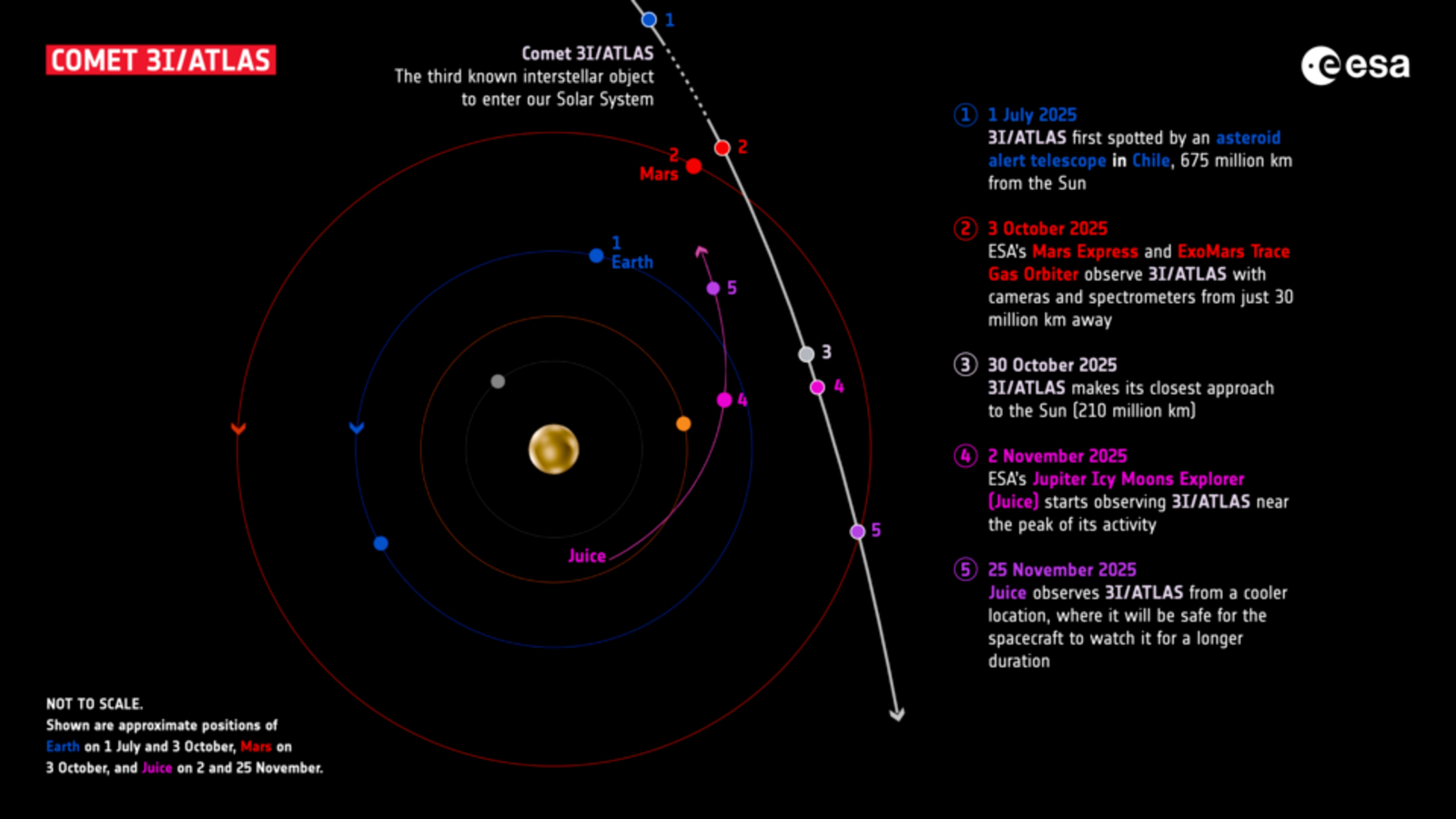

The interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS makes its closest approach to Earth this week, coming within around 167 million miles (270 million kilometers) of our planet on Friday (Dec. 19).

Astronomers worldwide are studying the comet, which is only the third interstellar object ever recorded in our solar system and potentially the oldest comet ever seen.

But it's not just space agencies getting in on the action. The United Nations' International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN) is about halfway through its 3I/ATLAS observing campaign, Live Science contributor Elizabeth Howell reports.

This is the first time that the IAWN network's observing campaigns have tracked an interstellar object.

To learn why, read the full story here.

3I/ATLAS Hulks out

Speaking of 3I/ATLAS, Brandon reported on Friday (while the blog was down) that the interstellar comet is changing hues as it approaches Earth.

Atop Hawaii's dormant Mauna Kea volcano, the Gemini North telescope confirmed that comet 3I/ATLAS has become greener and brighter since flying past the sun in late October.

Our home star heated up the interstellar object and, in doing so, made it much more active.

Find out what's driving the comet's greenish hue by reading the full story here.

Fancy a crossword?

Senior staff writer Harry Baker has just finished the latest Live Science crossword puzzle. Give it a go below if you're into that kind of thing.

Note: Our crosswords are currently best experienced on desktop.

New pumpkin toadlet is so smol!

A newfound species of pumpkin toadlet has caught our eye. Researchers announced the discovery in the journal PLOS One mid-last week, but we think it deserves a shout-out today.

The frog lives in the mountains of southern Brazil and belongs to a group of miniaturized diurnal (awake during the day) frogs called Brachycephalus, some of which are pumpkin colored — hence the name, "pumpkin toadlet."

The Brachycephalus genus boasts the smallest known vertebrate in the world: A species known as B. pulex, whose females average just 0.32 inch (8.15 millimeters) in length and whose males are even shorter, at 0.28 inch (7.1 mm), which is smaller than a human fingernail.

This latest addition to the pumpkin froglet clan is a bit bigger, with a body length of up to 0.53 inch (13.4 mm). The frog is bright orange, as you'd expect, but distinguishes itself from other pumpkin froglets with small amounts of green and brown at irregular points on its body.

The researchers who made the discovery want the frog's territory in the Serra do Quiriri area of Brazil to be protected to safeguard its future, as well as other unique species that live there.

You've got to imagine that the researchers wanted this pumpkin toadlet study out closer to Halloween. Ah, well, it's a winter treat.

Hopping off

Time for me to sign off with the rest of the U.K. team. As always, keep checking back for more science news from our U.S. colleagues.

I'll leave you with this joke from The Conservation Volunteers.

What goes dot-dot croak, dot-dash croak?

Morse Toad!

Enormous genetic study groups psychiatric disorders

Live Science contributor Clarissa Brincat just covered the largest genetic analysis of psychiatric disorders to date. The study, which included data from more than 1 million people, found shared genetic profiles that unite different psychiatric disorders. Across 14 disorders — including anorexia, OCD, schizophrenia and ADHD — the analysis revealed five distinct groups that share similar genetics.

Some of these shared genetics point to shared biological mechanisms that may underpin the disorders. For instance, depression, PTSD and anxiety fell into one group that included genes associated with glia, the brain's nonneuronal support cells. That may hint that glia play a key role in the manifestations of each of these disorders.

However, an expert told Live Science that it's important to remember that correlation does not equal causation; a gene variant being linked to a given disorder doesn't mean it's a cause of that disorder. The genetics of psychiatric conditions are very complex, in that they interact with a person's environment and their experiences. Additionally, the genes tied to disorders can also be tied to traits like creativity or intelligence — it's not as if there's a "depression gene" or "PTSD gene" that does only one thing.

Tanning beds uniquely harmful to skin

Tanning beds are especially harmful to skin, a new study in the journal Science Advances suggests.

The study analyzed the medical records of around 32,000 patients who had visited a dermatology clinic at Northwestern University. Of these, more than 7,000 reported using tanning beds.

The team looked at a subset of the tanners and compared them with folks who did not use tanning beds. After controlling for various factors, such as risk factors for the deadly skin cancer melanoma, the team found that using tanning beds multiplied the odds of developing melanoma by a factor of 2.85. There was also a subtle-sign of causality — a "dose-response" relationship whereby more tanning led to higher risk.

They also took biopsies from 11 of the tanning bed users in the study, who went to a "high risk" skin cancer clinic, as well as from six cadavers, who presumably had normal risk of skin cancer. They then looked for molecular signs of DNA damage in the skin. They compared those against data from a vast database of people, known as the U.K. biobank.

Tanning seemed to induce unique signatures of DNA damage that were somewhat different from those due to general sunlight exposure. And tanning beds exposed more of the skin to UV light, as well as exposing skin not typically exposed to high levels (presumably because people tan their whole body in such beds, versus wearing coverups or swimsuits outdoors).

Young people who tanned frequently also had more mutations in their skin than people who were twice their age, the study found.

"We found that tanning bed users in their 30s and 40s had even more mutations than people in the general population who were in their 70s and 80s," study co-author Bishal Tandukar, a postdoc of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a statement. "In other words, the skin of tanning bed users appeared decades older at the genetic level."

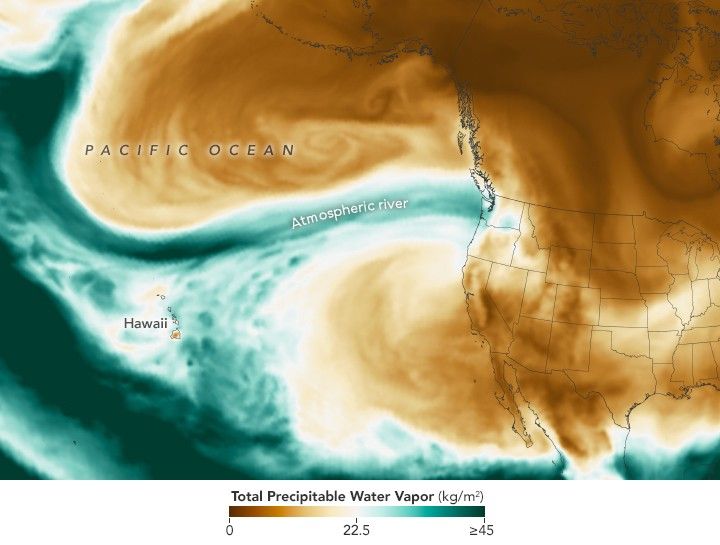

Levee fails near Seattle-Tacoma International Airport

A levee has been breached near Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, prompting the National Weather Service in Seattle to issue a flash flood warning for the populated area of about 46,000 people.

The Green River breach happened in the city of Tukwila, which is around 11 miles (17 kilometers) south of Seattle. The area also has one hospital and two schools.

"Leave immediately if you are in this area," Washington Governor Bob Ferguson stated, according to mynorthwest.com. "Conditions are dangerous and access routes may be lost at any time … Do not drive or walk through standing or moving water. Turn around, don't drown. Do not drive around barricades or road closures."

Atmospheric rivers have pummeled the areas around Seattle for the past week and into this one, stranding people on the roofs of their cars and houses. In the Pacific Northwest, atmospheric rivers "are long, narrow storm systems that cross the Pacific Ocean," KUOW environment reporter John Ryan reported. "They funnel moisture up from the subtropics, hence their local nickname the Pineapple Express, and they're perfectly normal this time of year and how the Northwest gets a lot of its winter precipitation. But the bigger atmospheric rivers, they do cause flooding."

While it's unclear if climate change is driving the current atmospheric rivers, studies have found that a "hotter climate will mean more frequent atmospheric rivers and rivers that last longer and deliver more rain," Ryan said. "And that's because, really simply, that warmer air can hold more water, and then it can unleash more of that water when it's time to rain, and that's expected to drive more flooding. And as the climate warms, we'll also be expecting more precipitation in our winters coming as rain instead of snow. And snow, of course, melts slowly over months, but rain can run off instantly and cause big flooding."

I'm from Seattle, so I've been keeping an eye on the horrific flooding that's been happening in the region. I've seen videos of a house being swept away in fast currents, the famous Snoqualmie Falls bursting at its seams, elk swimming across a flooded field by a middle school, and people kayaking along waterways that were once streets. It's heart wrenching to see, and I'm hoping everyone in the region is staying as safe as they can.

3I/ATLAS glows red in new X-ray image

The interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is cruising toward its closest approach to Earth this week (Dec. 19), and the planet's science agencies are observing it with everything they’ve got.

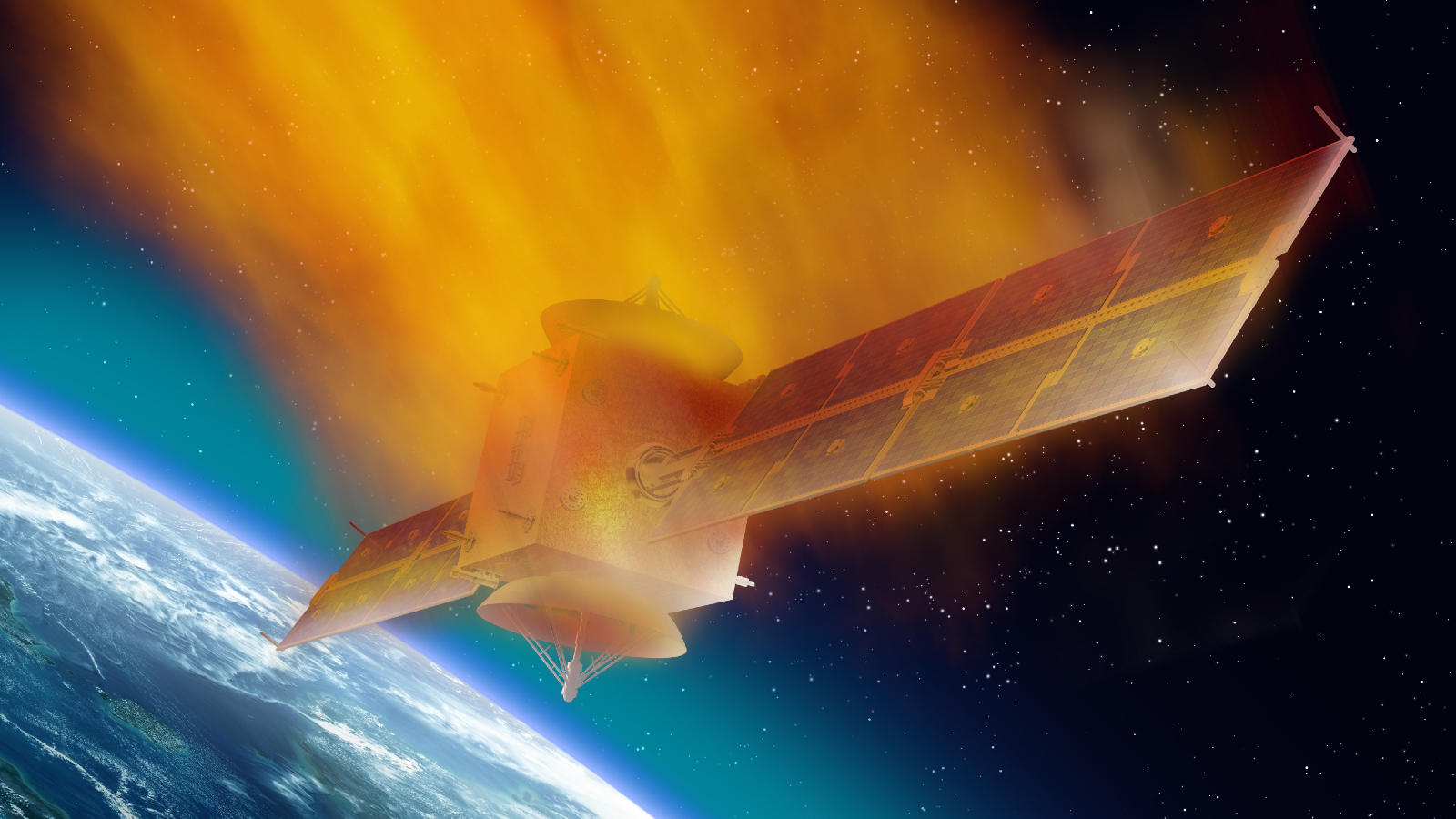

Images released last week by the Gemini North observatory in Hawaii show the comet taking on a brighter, greener hue after being warmed up by the sun, causing it to leak clouds of green-glowing diatomic carbon gas. Now, the latest 3I/ATLAS image from the European Space Agency (ESA) shows the familiar comet in a new light: red X-rays.

Taken with the XMM-Newton satellite, the images show high-energy X-ray emissions surrounding the comet, with darker blue regions of space behind it. These emissions are the result of charged solar radiation slamming into the comet's coma — the thin atmosphere of gas that surrounds the comet's main body and feeds its tail.

Studying these emissions should help scientists better understand what the comet is made of, with gases like hydrogen and nitrogen being especially easy to detect with X-ray telescopes, according to ESA.

The images were taken when the comet was roughly 175 million miles (282 million km) from the spacecraft, which is about as close as 3I/ATLAS will get to Earth this week. In addition to ESA and NASA, dozens of observatories around the world are watching the comet in cooperation with the U.N.'s International Asteroid Warning Network, which tracks transient near-Earth objects.

Stay tuned for more images this week.

30 models of the universe are wrong

Thirty different cosmological models have been ruled out thanks to years of data from Chile's Atacama Cosmology Telescope, which winked on in 2007 and shut down in 2022. The telescope’s final data release hints that theoretical physicists may need to go back to the drawing board to explain the Hubble tension, or the fact that the universe seems to be expanding at different rates depending on how you measure it, Live Science contributor and astrophysicist Paul Sutter reports.

To learn more about why the data is so powerful, and why so many models of the universe keep failing, read the full story here.

Thirty different cosmological models have been ruled out thanks to years of data from Chile's Atacama Cosmology Telescope, which winked on in 2007 and shut down in 2022. The telescope’s final data release hints that theoretical physicists may need to go back to the drawing board to explain the Hubble tension, or the fact that the universe seems to be expanding at different rates depending on how you measure it, Live Science contributor and astrophysicist Paul Sutter reports.

To learn more about why the data is so powerful, and why so many models of the universe keep failing, read the full story here.

Going out with a (big) bang

The U.S. team is signing off for the evening, but the U.K team will be back with new science tomorrow.

In honor of all those failed cosmological models, we'll leave you with this enlightening joke:

How many astronomers does it take to screw in a lightbulb?

Zero. They use standard candles!

I'll let myself out.

Wake up, new 3I/ATLAS preprint just dropped

Good morning, science fans! Patrick here to kick off the day's science news blog coverage. I want to start with new comet 3I/ATLAS research.

Astronomers have detected a "wobbling high-latitude jet" in everyone's favorite interstellar object, according to a preprint paper, which appeared on arXiv today.

This is the first time scientists have detected a spinning jet on an interstellar comet, and it may indicate that the comet's nucleus is rotating rapidly as it moves through space.

Researchers observed the comet from the Teide Observatory on the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands. Their letter, and findings, have been accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Comet 3I/ATLAS will make its closest approach to Earth on Friday, so stay tuned.

Bury Rex with his favorite dagger

Stone Age fishers buried a dog next to a dagger in a Swedish lake bed, staff writer Kristina reports.

Archaeologists are investigating the mysterious 5,000-year-old burial, which may represent a previously unknown ritual.

The burial was uncovered during a high-speed railway construction project about 22 miles (35 kilometers) southwest of Stockholm. Today, the lake is a swampy bog, but during the Stone Age, it was clear and filled with fish.

You can read the full story here.

Gigantic sinkholes in Turkey

Almost 700 sinkholes have opened up in Turkey due to extreme drought and groundwater extraction.

Turkey's Disaster and Emergency Management Authority found 684 sinkholes in the country's wheat-growing region of Konya Plain as part of a recent sinkhole assessment, AccuWeather reports.

The sinkholes began appearing in the 2000s, but this year has seen the emergence of more than 20 new, large sinkholes. Some of the holes are hundreds of feet wide and more than 100 feet (30 meters) deep.

Live Science news roundup

Here are some of the best Live Science stories from yesterday and this morning that we haven't covered on the blog:

Down to Earth with a bump

The likelihood of Earth’s satellites causing a massive orbital pile-up are increasing dramatically, a new preprint study warns, with the estimated time it takes for a catastrophic space collision to occur among unsupervised satellites dropping from 121 days in 2018 to just 2.8 days today.

And one satellite crash can quickly lead to others, causing a chain reaction of debris called Kessler syndrome, which was popularly depicted in the 2013 film "Gravity."

Although a cascade of this kind has yet to happen, scientists are increasingly concerned that the growing number of satellite megaconstellations and space junk is making it more likely. Currently, the Department of Defense tracks the 30,000 largest debris pieces, but there are many more that are too small to be followed, according to NASA.

'The birth dose was a safety net': Expert reacts to new vaccine guidance

In early December, a committee that steers federal vaccine policy rolled back a universal recommendation for newborns to receive their first dose of hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth. Now, the committee instead says that children of mothers who test negative for the virus get the vaccine at 2 months old.

In a new opinion for CIDRAP, infectious diseases specialist Dr. Jake Scott lays out exactly why that's a bad idea.

"The committee's decision assumes prenatal screening reliably identifies at-risk infants," Scott writes. "It does not."

There are many known gaps in hep B screening: 14% of pregnant people are never tested for the virus; people can become newly infected after a negative test; and babies can be exposed by others even if their mothers test negative. The examples go on, but universal newborn vaccination sidestepped all these vulnerabilities, Scott says.

"The birth dose was a safety net. Safety nets exist for patients the system fails to catch," he continues. "That is who will pay for this decision."

Hepatitis B has no cure, and when the virus is contracted in infancy or early childhood, it turns into a chronic infection about 90% of the time, Scott explains. That chronic infection can lead to liver scarring (cirrhosis) and liver cancer, which ultimately leads to early death in up to 1 in 4 people who catch the virus as babies.

Following the vaccine committee's vote, "modeling estimates project 1,400 additional chronic pediatric hepatitis B infections per year, approximately 300 additional cases of liver cancer, and 480 preventable deaths over the lifetimes of these children — along with more than $222 million in excess annual health care costs," Scott said.

Glaciers reach peak extinction rate

We’ve written our fair share of stories on climate tipping points and glacial retreat, but this one managed to catch even us by surprise.

A new study published in Nature Climate Change has revealed that the peak rate of glacial extinction is much closer than we first thought — arriving in the European Alps by 2033 and the U.S. and Canada by 2040. This maximum rate of loss is then expected to plateau until 2060, causing 80% of the world’s glaciers to disappear before the end of the century.

That’s terrible news for settlements both in the mountains and near sea level, but it will also have wider impacts on climate patterns and ocean currents the world over.

The solution? You guessed it, rapid and deep cuts to fossil fuel emissions, which could stem annual glacier losses to a peak of roughly 2,000 a year in 2040, followed by a decline.

Signing off

That's all from us on the U.K. side, but stick with our North American colleagues for more updates. And why not a satellite joke before we go?

Actually, nevermind, those never land.

Polar bears evolving

There's a small bit of good news for polar bears, those perennially beleaguered poster children for the impacts of climate change.

It seems that the adorable, iconic bears may be rewriting their own DNA in order to survive melting sea ice.

To learn more about how polar bears are evolving in response to diminished ice cover, read the full story, by Live Science contributor Sarah Wild.

Why heart attack outcomes are worse during the day

Heart attacks cause more extensive damage when they happen during the day than when they occur at night — and the reasons for that are still being unraveled.

Live Science contributor Zunnash Khan just covered a new mouse study that starts to reveal the role of the immune system in this pattern. It turns out that immune cells called neutrophils, which become more active during the day, contribute to the inflammation and knock-on damage seen with daytime heart attacks. The study authors found several ways to shift these neutrophils into "night mode," and by doing so, they were able to reduce heart attack damage in mouse models.

That raises the possibility that there could be a way to replicate these results in humans and thus innovate new and better heart attack treatments.

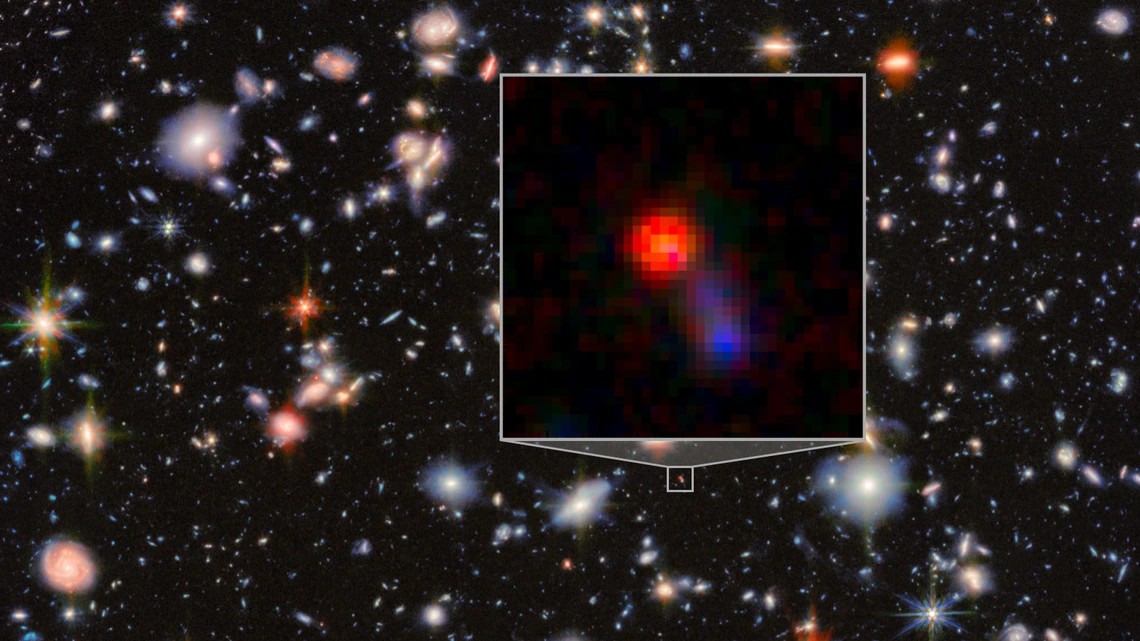

Did Webb spot the oldest supernova?

In March 2025, a mysterious, high-energy explosion came blazing out of the early universe. Within days of the blast’s detection, the James Webb Space Telescope zoomed in on the event to probe its origins.

Now, new research hints that the blast may have been triggered by the earliest known supernova in the universe. Just how ancient and distant was it? Live Science contributor Shreejaya Karantha has the story.

The most dangerous dams in the U.S.

New satellite imagery reveals that dams in the U.S. are in worse shape than we thought: The first ever national survey reveals that 2,500 of the 16,700 dams in the country are in poor condition — and many of the most imperiled dams are poised to destroy socially vulnerable communities, former Live Science intern Sierra Bouchér wrote for the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

The results will be presented at the AGU annual meeting in New Orleans on Wednesday (Dec. 17).

The study utilized radar data from the Sentinel-1 satellite, along with structural data and flood hazard maps to estimate how extensively different dams had sunk over a 10-year period, and what danger they posed to nearby communities.

Most dams in the country were built during a boom in the 1950s and 1960s, making the average one decades old. And many were in worse condition than previously thought, according to the research.

Climate change adds extra stress to these aging levees by increasing extreme weather, heavy rainfall and flash flooding events, pushing many of these dams to their limits.

Just yesterday (Dec. 15), the Green River levee was breached, raising the specter of flash flooding in Tukwila, south of Seattle, Washington. In 2017, heavy rainfall caused severe damage to the Oroville Dam spillway in Northern California, forcing evacuations downstream.

The U.S. has so far avoided a catastrophic hydropower dam failure, but if one were to break, it would be "a disaster,” study author Mohammad Khorrami, a geoscientist at Virginia Tech said in the AGU statement. "Some of the dams actually serve as a sub-buffer for water that's used for agriculture and for electricity production. Those dams can create a ripple effect if they fail that can impact the national economy."

Still, that doesn't mean disaster is inevitable. Many of the dams are in poor condition due to deferred maintenance, Khorrami noted. Investing in the infrastructure now could thus head off future catastrophes.

Of course, with massive cuts to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) preparedness budget, it's unclear how many local authorities will choose to shore up their aging infrastructure.

Goodnight!

The U.S. team is heading out for the evening but the U.K. folks will be back online in the A.M.

I'll leave you with this well-known math joke:

Q. What's the difference between a doughnut and a coffee cup?

A. Nothing (if you're a topologist)

Blast off!

Good morning, science fans! Patrick here with more science news. I'm launching today's blog coverage with, rather appropriately, a launch.

Europe's Ariane 6 rocket blasted off into space this morning, carrying two more satellites for the Galileo satellite navigation programme. You can watch the full launch by clicking on the video above.

Ariane 6 is a heavy-lift launcher designed to carry heavy payloads. The pair of satellites it took to space today will join 26 other active satellites and act as spares to "improve the robustness" of the Galileo satellite navigation system, which serves five billion smartphone users worldwide, according to the European Space Agency.

The rocket left Europe's Spaceport in French Guiana at 2:01 a.m. local time (12:01 a.m. EST), Space.com reported.

Bear with us

Bears living around villages in the mountains of Italy have evolved to be smaller and less aggressive.

In a Molecular Biology and Evolution study published Monday, researchers detailed how human activity influenced selection pressures on the genes of central Italy's Apennine brown bears.

The Apennine bear population is small, lives in close proximity to humans, and has been isolated from other brown bears since Roman times.

As a result of their isolation, the researchers say that the bears have several unique characteristics that distinguish them from other brown bears, including the smaller bodies and less aggressive personalities.

The researchers think that the bears' behavior-related genes were influenced by humans removing (killing) more aggressive bears until the population as a whole became less aggressive on average.

Of course, they're still bears, so if you visit the region, please don't try to pet one.

Live Science news roundup

Here are some of the best Live Science stories from yesterday that we haven't covered on the blog:

Come in, MAVEN

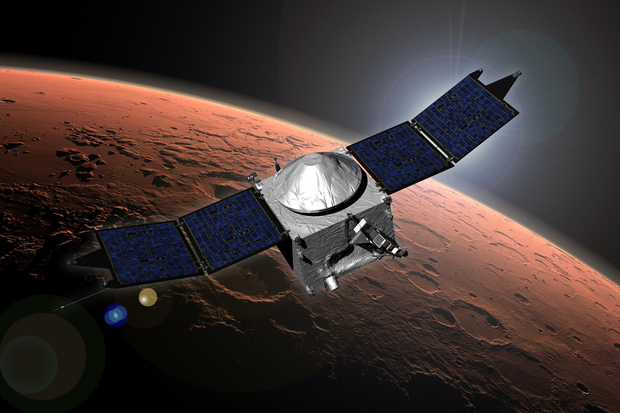

Last week, we wrote about NASA losing contact with its Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) spacecraft. Well, things aren't looking good for the probe, Live Science's sister site Space.com reports.

On Monday, NASA announced that efforts to reestablish contact with the spacecraft had been unsuccessful thus far.

MAVEN has been orbiting Mars for more than a decade, collecting data on the Martian atmosphere and acting as a communications relay station for Mars rovers.

The orbiter appeared to be working fine before traveling around the far side of the Red Planet earlier this month, but couldn't be reached when it reemerged on Dec. 9. NASA did recover a fragment of MAVEN's tracking data from Dec. 6, but it wasn't comforting.

"Analysis of that signal suggests that the MAVEN spacecraft was rotating in an unexpected manner when it emerged from behind Mars," Erin Morton, a NASA spokesperson, wrote in the Monday update. "Further, the frequency of the tracking signal suggests MAVEN’s orbit trajectory may have changed."

Stay tuned for any further MAVEN updates.

Bad vibes

Digital privacy experts have flagged a new, and incredibly icky, frontier for data snooping — app-connected sex toys, Wired reports.

The encroachment of data collection has been a steady ratchet in recent years, but now this spying is taking place in even the most intimate areas of our personal lives, with companies using sex toys to collect sexual behavior data, usage frequency, intensity settings, partner connections, location data, and IP addresses.

Some of the companies spoken to by Wired claim these are for marketing purposes, enabling them to sell better toys to users in future. Yet with policies being less than clear on just how this data is kept and protected, it places an onerous burden on consumers to guard their digital privacy.

Check out the full story here.

Icequakes at the Doomsday glacier

A researcher has detected hundreds of glacial earthquakes reverberating from Antarctica's "Doomsday glacier", giving scientists a new window to study the potential instability of the glacier.

The Doomsday Glacier, more formally known as The Thwaites Glacier, earned its cheerful nickname because of the increasingly unstable Florida-sized chunk of ice's potential to raise sea global levels by as much as 3 feet (10 meters) — a tipping point it appears to be steadily edging toward.

That makes studying the newly-detected earthquakes (360 of which were detected between 2010 and 2023 and whose exact cause is unknown) vital work in sizing up the glacier's future prospects, Thanh-Son Pham, the seismologist who found the quake signals, writes.

Check out his article in The Conversation here.

Climate change has already made us poorer

When we write about climate change, it’s usually in the form of gloomy scientific predictions on its detrimental effects in the near future.

But greenhouse gas emissions are already hitting Americans in the wallet today, reducing U.S. income by an estimated 12%, a new study claims. And that’s purely from temperature shifts leading to more warm days, without factoring in the untold damage from extreme weather events.

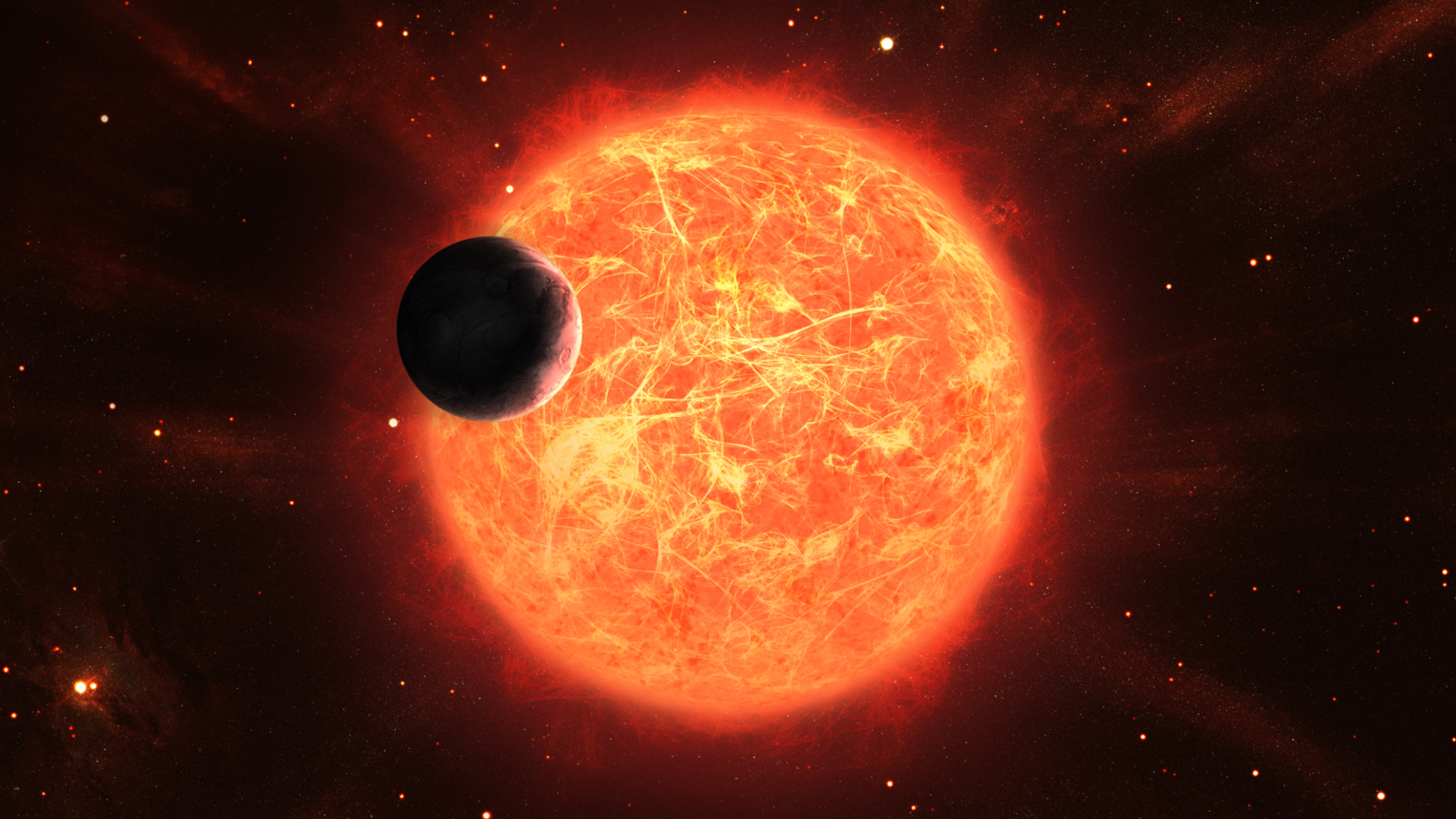

Earth-like planets could be way more common

Following that string of gloomy climate posts, you may be tempted to hop on a spaceship and go looking for an unruined planet.

Well, there’s good news on that front at least — Earth-like planets could be far more common than first thought.

For rocky planets like our own to form, they need to take material from nearby stellar explosions, or supernovas. But that raises a tricky question: How did our solar system get its material from supernovas without being blown up?

Scientists initially believed this could make planets like Earth rare cosmic flukes, but another team has an answer that could resolve the paradox. Check out the story by 404 Media for more.

Anglo-Saxon gold diggers

Two metal detectorists in England have stumbled on a cache of five Anglo-Saxon jewels from the seventh century.

But the gold-and-garnet accessories were not part of a high-status burial, which surprised archaeologists. In a new study, archaeologist Lisa Brundle details the jewels and offers explanations for why these antique pendants ended up together.

Read my full report here.

'Jekyll and Hyde' galaxy

Last week, I told you that NASA's James Webb Space Telescope had detected a supermassive black hole hiding in an ancient "Jekyll and Hyde" galaxy.

The galaxy, dubbed Virgil, looks like an ordinary star-forming galaxy when observed in optical wavelengths, but when viewed in infrared, transforms to reveal a monster black hole in its core.

I've now written a news story about the discovery, which suggests that our universe's most extreme objects could be invisible unless observed in infrared wavelengths.

Read the full story here.

Goodbye for now

That's us on the UK side signing off for tonight, but keep checking back for more updates from our colleagues across the pond!

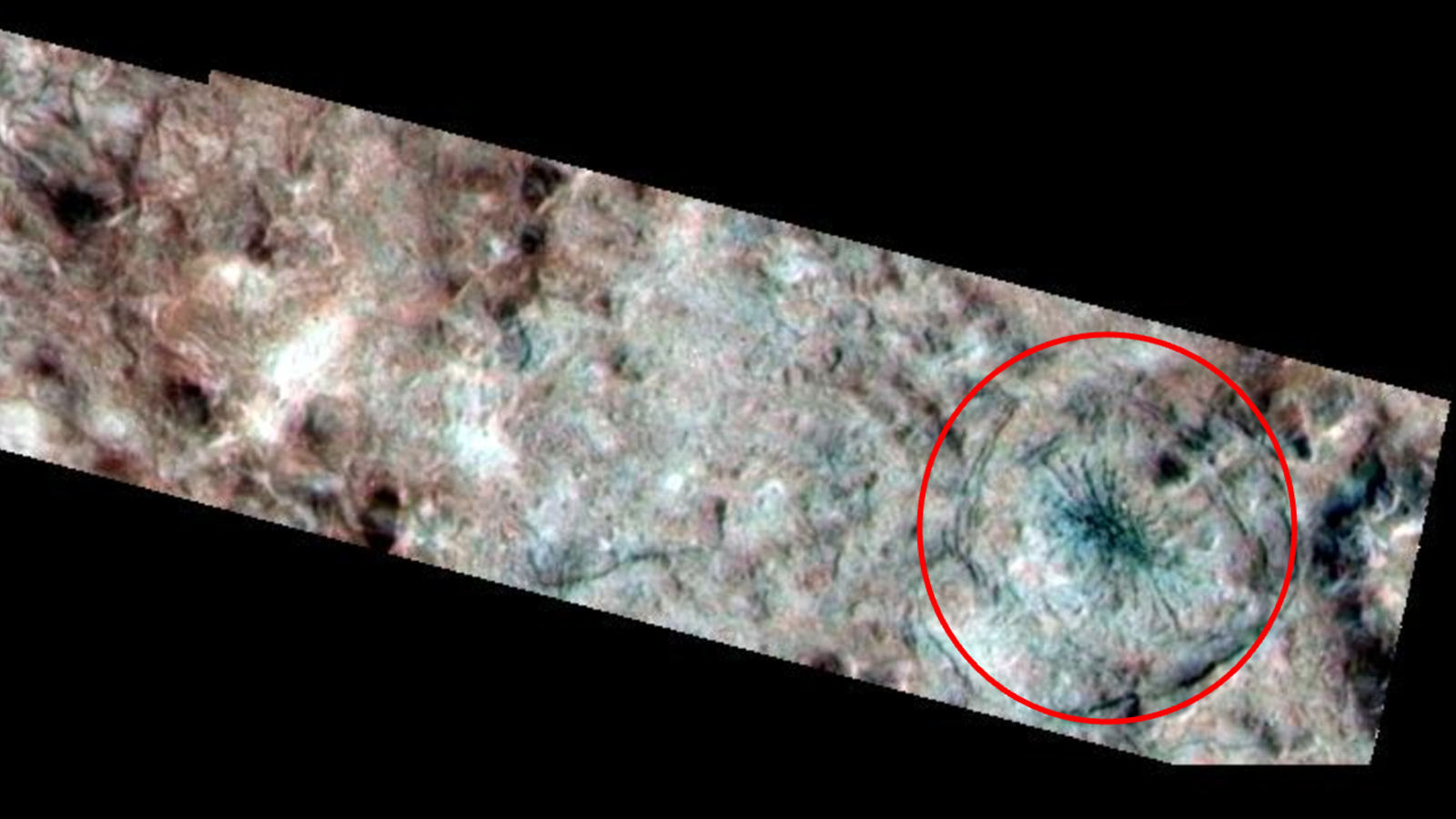

Secrets of spider 'demon' lurking on Jupiter

In a fun new story, Live Science senior writer Harry Baker has shed light on an enduring solar system mystery: What created the "spiders" that appeared on Jupiter during the 1998 Europa mission.

Initial theories suggested they were cracks formed by the gas giant's extreme gravity, or hydrothermal vent eruptions. It turns out, neither of those theories was quite right, and the answer was a much more Earthly explanation.

So what exactly was this arachnid "demon"? Read the full story to find out.

Pumas are feasting on penguins in Patagonia

Pumas are acting strangely at a national park in Patagonia, Argentina. Back in the 20th century, sheep farmers forced out pumas. But after a national park was established in 2004, the pumas began coming back — and they were hungry.

The pumas set their sights on a colony of roughly 40,000 Magellanic penguins that had settled in while the big cats were away. (Probably a nasty shock for the penguins.)

But now, a new study finds that the pumas that are eating these penguins are showing an unusual behavior.

Live Science contributor Skyler Ware covered the finding — you can read it here.

Into the "twilight zone"

Have you ever wondered what it takes to dive into the ocean's enigmatic "twilight zone," around 130 to 490 feet (39 to 149 meters) underwater?

In a new feature, National Geographic contributor Annie Roth recounts a recent dive made by brave "aquanauts" specially trained to explore these depths. Their mission took them to Blue Hole, an underwater sinkhole off Guam, where they were tasked with retrieving autonomous reef monitoring structures (ARMS) that had been placed there 8 years prior. By now, those ARMS are teeming with sealife, including species never-before-seen by humans, the team discovered.

Read more at National Geographic.

An ancient Egyptian temple revealed

Archaeologists working in a valley in Egypt have excavated a massive, 4,500-year-old temple dedicated to the sun god Ra. Even more intriguing, it's connected to another, "high" temple. Interestingly, ancient people used to float up to the valley temple by boat, before walking up a large ramp to the higher temple.

Live Science contributor Owen Jarus has more details on what was found at the site — and what the site became after the temple was no longer used.

Over and out

The U.S. team's day is over, but look out for new science updates from the U.K. folks first thing in the morning.

We'll leave you with this joke from Beano:

Why don't you ever see penguins in Great Britain?

Because they're scared of Wales!

Comet 3I/ATLAS incoming

Good morning, science fans! Patrick here to kick off a special comet edition of the science news blog coverage.

The interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is zipping past Earth tonight, making its closest approach in the early hours of tomorrow morning.

Today's live blog will serve as a countdown to the exciting celestial event. We're going to tell you everything you need to know about comet 3I/ATLAS and why astronomers are so interested in this rare, interstellar interloper.

What is comet 3I/ATLAS?

Comet 3I/ATLAS is a rare interstellar object from outside of our solar system. It's only the third interstellar visitor ever detected and could be the oldest comet ever seen.

The comet was first discovered in July, when it was seen hurtling past Jupiter at around 221,000 kilometers per hour (137,000 miles per hour). Having reached the closest point to our sun (perihelion) at the end of October, 3I/ATLAS is now making its way out of our solar system.

Researchers aren't yet certain of 3I/ATLAS's size, but Hubble Space Telescope observations suggest that it's somewhere between 1,400 feet (440 meters) and 3.5 miles (5.6 kilometers) wide.

Comet 3I/ATLAS roundup

We've written a lot of stories about comet 3I/ATLAS. Here's a small selection of our coverage:

- The UN's International Asteroid Warning Network is closely watching comet 3I/ATLAS. Here's why.

- Comet 3I/ATLAS is getting greener and brighter as it approaches Earth, new images reveal

- Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is erupting in 'ice volcanoes', new images suggest

- How dangerous are interstellar objects like 3I/ATLAS?

What time will the comet pass Earth?

Comet 3I/ATLAS is expected to make its closest approach to Earth at 01:01 a.m. EST (06:01 U.T.), according to data from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

And how close will it get?

The comet will get within about 168 million miles (270 million kilometers, or 1.8 astronomical units) of Earth, according to NASA.

This is relatively close when you consider the vastness of space, but not all that close. For context, the sun is 1 astronomical unit away, so the comet will be almost twice as far as the sun.

There's no danger that the comet will collide with Earth.

Where did comet 3I/ATLAS come from?

Comet 3I/ATLAS came from somewhere beyond our solar system, but we can't be much more specific than that.

Astronomers don't know which star system forged comet 3I/ATLAS. Given its speed, the comet has likely travelled a very long way and could be more than 7 billion years old.

Deciphering the comet's true origins may be beyond scientists' reach, particularly as billions of years of exposure to cosmic rays has transformed its exterior to the point that it no longer resembles the conditions in which it formed.

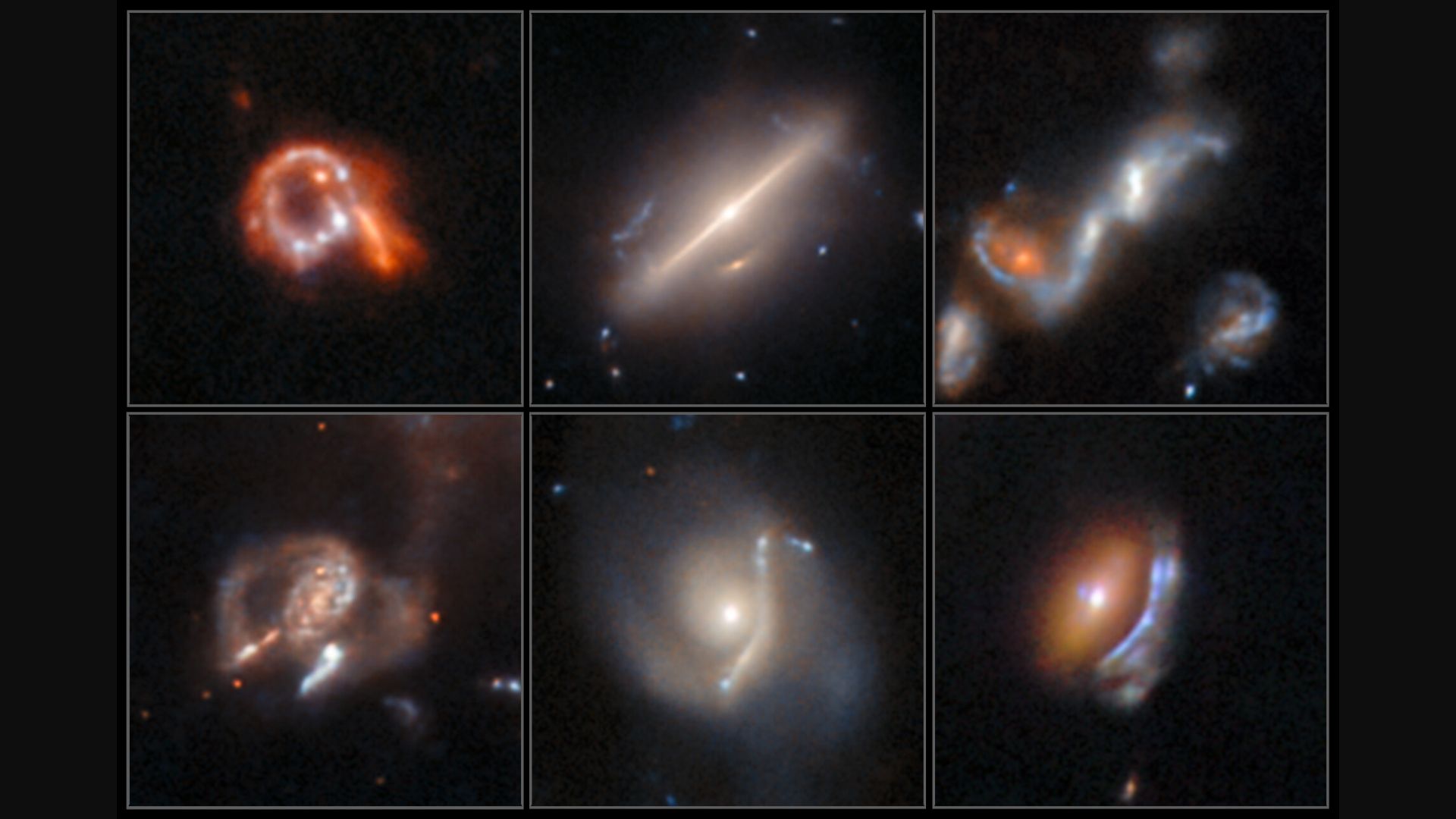

3I/ATLAS image gallery

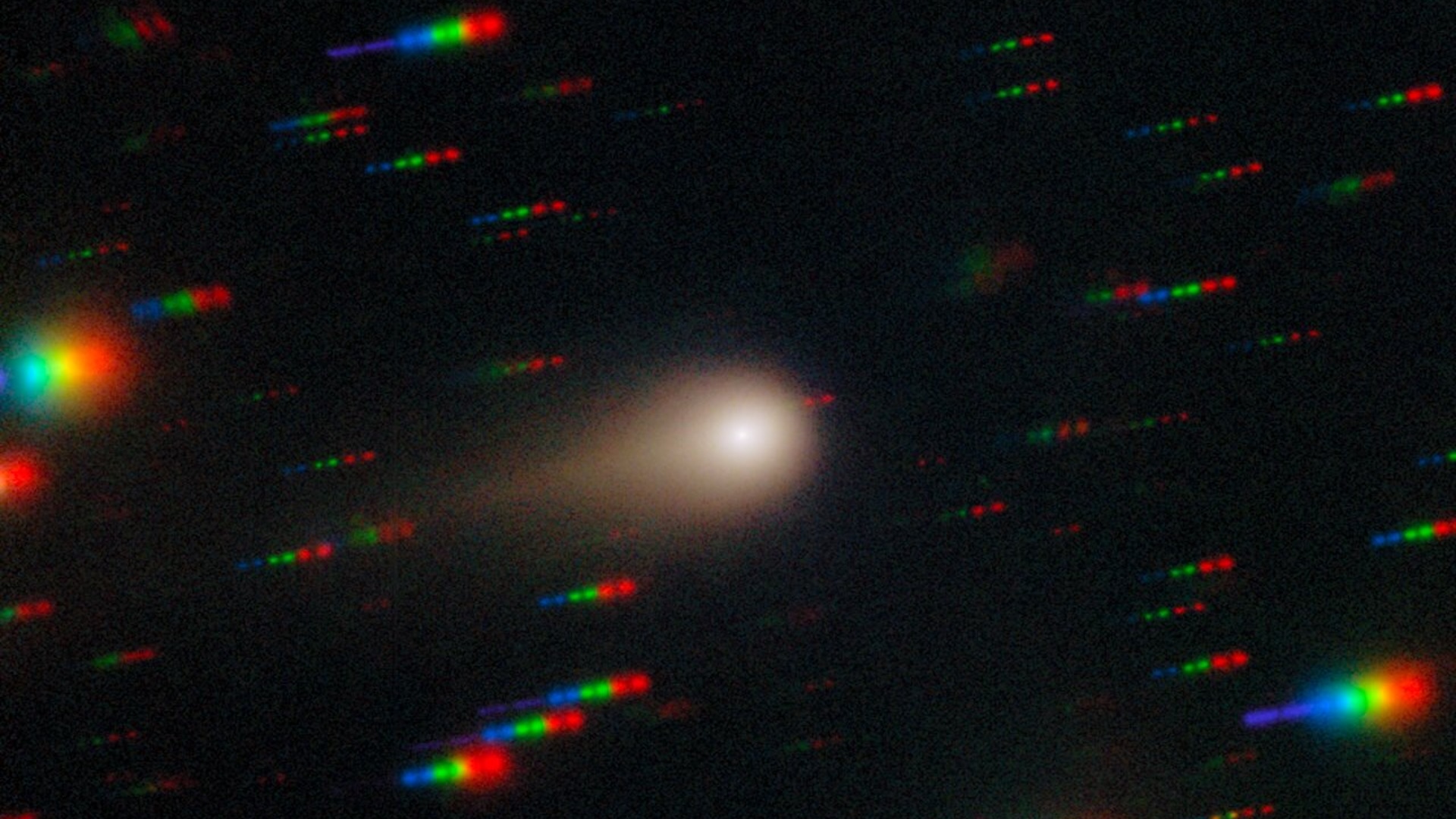

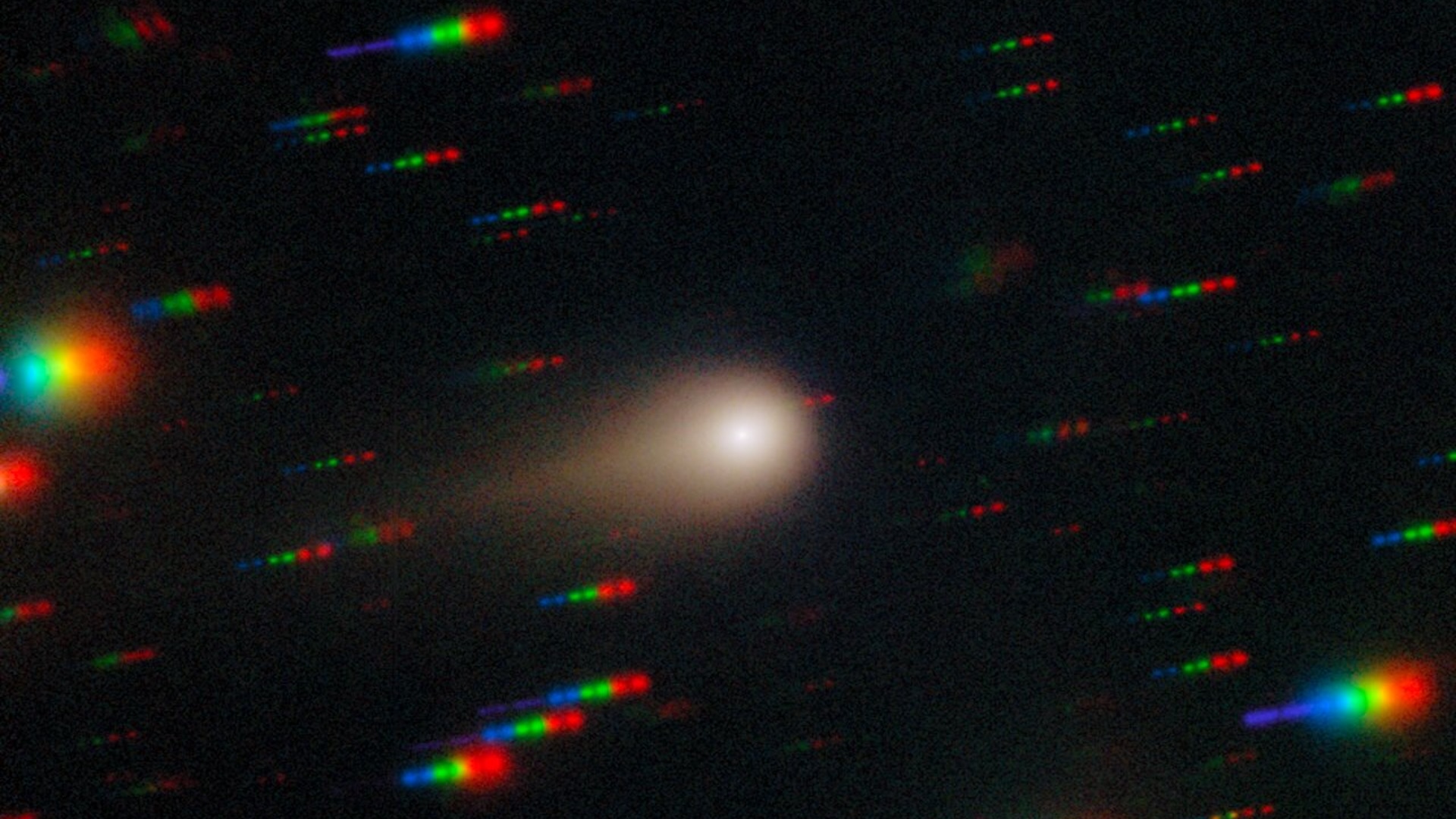

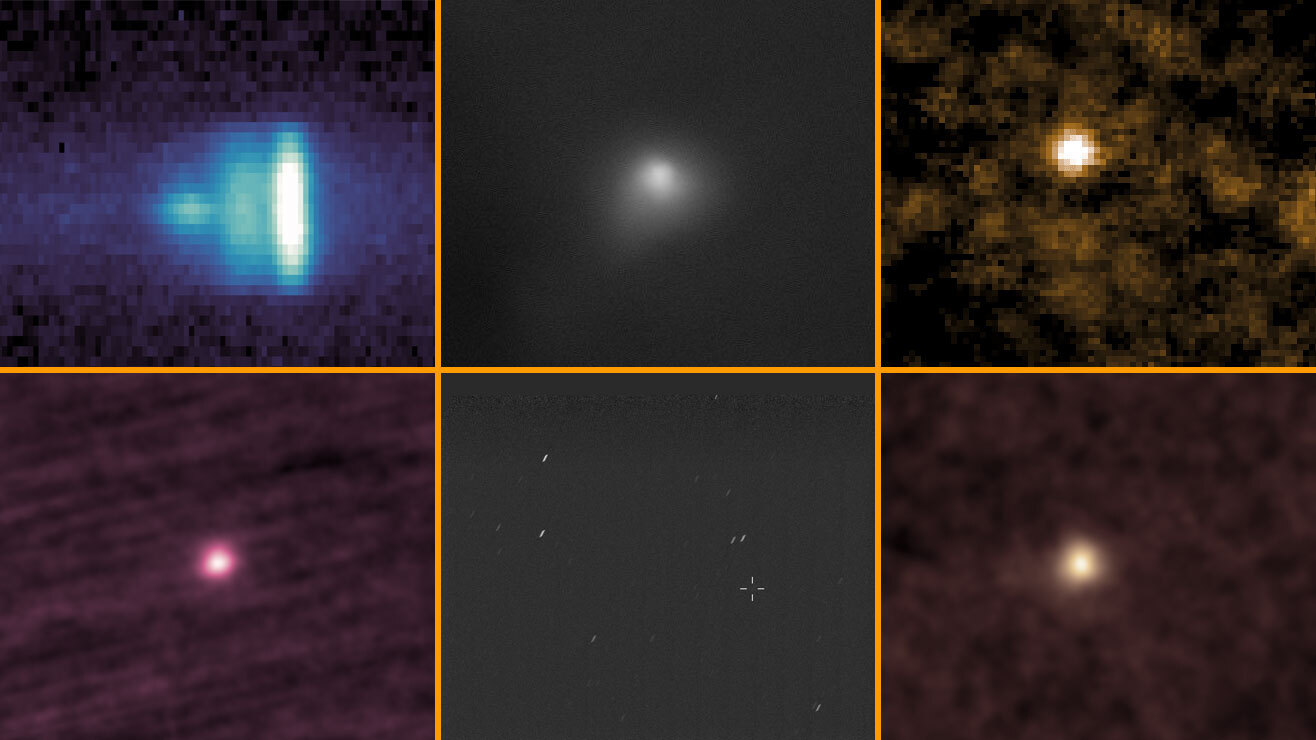

Hubble captured this image of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS on July 21, 2025, when the comet was 277 million miles from Earth. Hubble shows that the comet has a teardrop-shaped cocoon of dust coming off its solid, icy nucleus.

Satoru Murata, a New Mexico-based photographer, snapped this photo of Comet 3I/ATLAS on Nov. 16. The comet shows off its long tail and secondary anti-tail as a distant galaxy appears in the background.

In this image, comet 3I/ATLAS appears to have spiral jets shooting off its surface, which the authors of a preprint interpret as erupting "ice volcanoes."

A selection of images of the comet taken by various NASA spacecraft, and released during a much anticipated news conference last month.

So why are all these comet images so blurry?

Given the interest and speculation surrounding the comet in the press and on social media, you’d be forgiven for wanting some slightly crisper images of the interstellar visitor.

But alas, we’re going to have to disappoint: There’s simply no way to take clear images of a chunk of dirty ice that's just several miles across, zooming past Earth at a speed of 130,000 mph (210,000 km/h) and more than twice the distance between us and the sun.

That means that while many of these images are giving scientists a lot of new insights into the comet’s behavior, they’re hardly the most photogenic.

Why are scientists excited about the comet?

It's not every day that researchers get to observe an interstellar comet. Comet 3I/ATLAS is only the third interstellar object ever recorded. Its discovery follows those of the cigar-shaped 1I/'Oumuamua comet in 2017 and the pristine 2I/Borisov comet in 2019.

Each new comet from beyond our solar system is offering researchers a rare opportunity to learn more about conditions beyond our solar system, their chemistry, and their suitability for life.

So far, each interstellar visitor has displayed some differing characteristics, suggesting that there could be a variety of comet and planet-forming environments in the universe. Comet 3I/ATLAS has several intriguing properties, including its large size and unique chemical composition.

There has been some frenzied speculation that 3I/ATLAS could be an alien probe, which has elevated it to the status of celebrity comet. Yet 3I/ATLAS is almost certainly a natural object, which is unfortunate (or fortunate, depending on your perspective, personally I’ve had a busy enough year).

Okay, are you sure it’s not actually aliens?

If you want the short answer: Yes, most scientists are almost certain that 3I/ATLAS is not a probe, a spaceship, or really anything but a comet from an unknown star system.

One notable exception is Harvard University astrophysicist Avi Loeb, who has been giving interviews, writing blog posts and has co-authored a preprint about the possibility that comet 3I/ATLAS might be an alien spacecraft.

Loeb's assertions have drawn strong criticism from astronomers, especially as this isn't the first time he's made similar claims: Loeb also stated that 2017’s 'Oumuamua was alien technology, and that a meteor that struck Earth in 2014 left alien spherules at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

Of course, there are plenty of people who believe, want to believe, or might find it very profitable to tell others that aliens are among us — or soon will be. For these people, comet 3I/ATLAS is an opportunity to start talking about their favourite subject. And hey, aliens are a fun thing to speculate about.

In the case of 3I/ATLAS, the alien speculation wasn't helped by the U.S. government shutdown, which ran from Oct. 1 to Nov. 12. This meant that NASA was silent and delayed releasing images while comet 3I/ATLAS flew behind the far side of the sun, reaching its closest point to the sun (perihelion) on Oct. 29.

Shortly after the shutdown ended, NASA shared its unreleased 3I/ATLAS images and came out swinging against what the space agency's Associate Administrator Amit Kshatriya described, very understatedly, as "the rumors."

"This object is a comet," Kshatriya said in a stream on Nov. 19. "It looks and behaves like a comet… and all evidence points to it being a comet. But this one came from outside the solar system, which makes it fascinating, exciting and scientifically very important."

As we've said before, comet 3I/ATLAS having natural origins shouldn't detract from what is a remarkable story. This object is only the third interstellar comet ever recorded,potentially the oldest comet ever seen, and the most massive of its kind.

A tail as old as time

Despite what it seems, the alien speculation swirling around comet 3I/ATLAS is hardly new behavior. Historically speaking, humans have been dependably far from normal when confronted by comets — taking them to be portents of plague, war or societal collapse.

For example, in 44 B.C. a comet that appeared in the sky after Julius Caesar’s murder was interpreted by his son, Octavian, as a sign the slain statesman had ascended to godhood, making it a powerful propaganda tool in Octavian's successful bid to become the first Roman emperor.

Similarly, the appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1066 was taken by the Normans as a big cosmic thumbs up for their invasion and conquering of England, and was later depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry.

In modern times, the discovery of what comets are and what they’re made of has only altered the character of the hysteria surrounding their appearances. Another pass of Halley Comet’s in 1910 came not long after the discovery of toxic cyanogen gas in its tail, sowing widespread panic and giving swindlers the opportunity to sell anti-comet pills and umbrellas.

In 1997, the appearance of Comet Hale-Bopp saw the emergence of the Heaven’s Gate cult, whose members tragically died by mass suicide, believing that they would be beamed aboard a spaceship flying behind the comet.

Latest comet 3I/ATLAS research

The latest research concerns the detection of a "wobbling high-latitude jet."

The jet is made of dust particles and was ignited by the sublimation of volatiles as the comet approached the sun in the summer, according to the team that detected it.

This is the first time scientists have detected a jet on an interstellar comet, and it may indicate that the comet's nucleus is rotating rapidly as it moves through space. The jet also explains a sunward-pointing anti-tail observed on the comet.

Researchers observed the jet from Teide Observatory on the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands. Their findings, first shared on Tuesday via the preprint server arXiv, have been accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Comet 3I/ATLAS livestream

A reminder that you can watch the comet zoom past in a livestream hosted by The Virtual Telescope Project, starting at 11 p.m. EST.

The Virtual Telescope Project plans to share real-time images of the comet as it makes its closest approach to Earth.

Brits away

Time for the U.K. team to sign off, so that's the end of our British cometary. Stay tuned for more 3I/ATLAS updates from our U.S. colleagues.

I'll leave you with this terrible joke that I just invented.

Why did comet 3I get lost?

It didn't have its ATLAS.

NASA's alien-hunting Clipper eyes 3I/ATLAS

The beguiling interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS will reach its closest point to Earth overnight tonight (Dec. 18-19) when it will swoop within about 168 million miles (270 million kilometers) of our planet. But the latest image release from NASA — taken with the Europa Clipper spacecraft — cuts the distance to 3I/ATLAS by a third.

Snapped on Nov. 6 from a distance of about 102 million miles (164 million km), the new image is the result of seven hours of observations with the spacecraft's Europa Ultraviolet Spectrograph (Europa-UVS) instrument.

Clipper is currently on its way to Jupiter, where it will scour the icy moon Europa for signs of life. To find out what it could teach us about 3I/ATLAS in the meantime, read my full story here.

How to see 3I/ATLAS tonight

Do you want to see comet 3I/ATLAS at its closest point to Earth?

Skywatching reporter Jamie Carter has you covered. In his latest article, he runs down the best way to catch the interstellar comet through a backyard telescope or good pair of binoculars.

And if, like me, you don't have the optical tech to see the comet in person, you can also catch a free online webcast tonight. Find all the details in Jamie's article here.

ATLAS, our comet’s swung around

Good morning, science fans! We’re kicking off the blog this morning with a goodbye to comet 3I/ATLAS, which reached its closest point to Earth last night and is now slowly leaving our solar system.

However, while it may be goodbye, it’s not yet farewell — the comet will make a long exit, crossing Jupiter’s orbit in 2026 and Pluto’s in 2029. That should give astronomers plenty of time to mine the ice chunk for observations; and for anyone else to claim its aliens, over and over again.

Patrick’s busy working on the story, which we’ll drop here when it’s ready.

DNA evidence of Bronze Age incest

A new DNA study of people buried in southern Italy 3,700 years ago has revealed a relationship that shocked archaeologists: A teenage boy's parents were father and daughter.

This case of "extreme parental consanguinity" is the earliest — and only — example of this type of union that archaeologists have ever discovered.

Read more about the Bronze Age community and their relationships here.

Live Science roundup

Here are some of the best Live Science stories from yesterday and this morning that we haven't covered on the blog:

Bellyaching Roman soldiers

A new study of soil from Roman latrines at the fort of Vindolanda in the U.K. has revealed that troops stationed there in the third century A.D were likely infected with at least three different parasites.

While two of the parasites — roundworm and whipworm — have been found at other Romano-British archaeological sites, researchers discovered the first ever evidence of Giardia duodenalis — a microorganism that diarrhea sufferers know well.

Read my article on the new research here to find out what G. duodenalis tells us about life on the Roman frontier.

Is AI coming for mathematicians' jobs?

Artificial intelligence models are making steady progress in cracking increasingly difficult math problems, but will they soon eclipse humans in cracking the hardest unsolved conjectures? Or is it all just hype?

Live Science contributor Kit Yates spoke with some of the world's best mathematicians to find out.

You can check out the full story here.

Did you wave to comet 3I/ATLAS?

As Ben wrote this morning, comet 3I/ATLAS made its closest approach to Earth overnight and the interstellar visitor is now moving away from us.

However, last night was far from our last chance to see the comet. The solar system invader has a long way to travel before researchers and skywatchers lose sight of it — a good thing, too, as I was in bed when 3I/ATLAS reached its closest point to Earth.

Find out more about the comet's Earth flyby and where it's heading with my new story, available to read here.

Comet livestream, take two

Yesterday, I told you that the Virtual Telescope Project was hosting a livestream of comet 3I/ATLAS passing Earth. Well, it got called off because of rain.

The good news is that the project is trying again tonight. Scheduled for 11 p.m. EST, the livestream will feature real-time images of the comet as it heads away from Earth.

You can tune in for free on the Virtual Telescope Project's YouTube channel.

Tattooed toddlers in Nubia

Archaeologists recently studied more than 1,000 mummies from the Nubian region of the Nile Valley using multispectral imaging in search of ancient tattoos. They found 27 people with geometric-style tattoos — and a lot of them were kids with dots tattooed in a diamond shape on their forehead.

Researchers think that the tattoos may be linked to the rise of Christianity in the region, perhaps as a kind of baptism for kids as young as 18 months old. But the tattoos may also have been a kind of protection against disease.

Read my full story on this new research here.

Closing time

The U.K. team is signing off, so that's all from us Brits. Keep checking back for more science news from our U.S. colleagues.

We're putting the live blog on pause next week — the holidays and all that. As a result, you won't hear from Ben or me again this year. I hope you've enjoyed our coverage. Thank you for tuning in!

I'll leave you with this joke from a blog called The Adventures of Parson Carson.

How do you organize a space party?

You planet.

Catch a speeding comet?

Comet 3I/ATLAS is now speeding away from us, soon after its closest approach. But that doesn't mean we've necessarily seen the last of this interstellar interloper.

Senior writer Harry Baker has a fascinating Science Spotlight piece detailing the plans to catch up with this interstellar visitor — or the next one to blast through our solar system.

You can read about the pros and cons of each plan to intercept the comet in his story.

Flu season hits the US in earnest; 3 pediatric deaths reported so far

Flu season typically peaks between December and February, and the U.S. is starting to feel that seasonal uptick now, the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) reports.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data shows that the rate of flu-like illnesses was "high" or "very high" in 14 states, as well as Puerto Rico, Washington, D.C., and New York City, during the week ending on Dec. 13. This coincided with a rising rate of positive diagnostic test results for influenza. Additionally, two pediatric deaths from influenza were reported this week; one additional pediatric death was reported earlier in the season, bringing the current total to three.

It's not too late to get vaccinated for this year's flu season. It's recommended that everyone 6 months and older who hasn't yet gotten a flu shot do so now.

Have a good weekend

The Live Science crew is signing off for the weekend. We're putting the blog on pause until next year, but keep checking the homepage for more science news.

In honor of the fast-receding 3I/ATLAS, we'll leave you with this joke.

Why does a shooting star taste better than a comet?

It's a little meteor.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.