Ancient burrowing bees made their nests in the tooth cavities and vertebrae of dead rodents, scientists discover

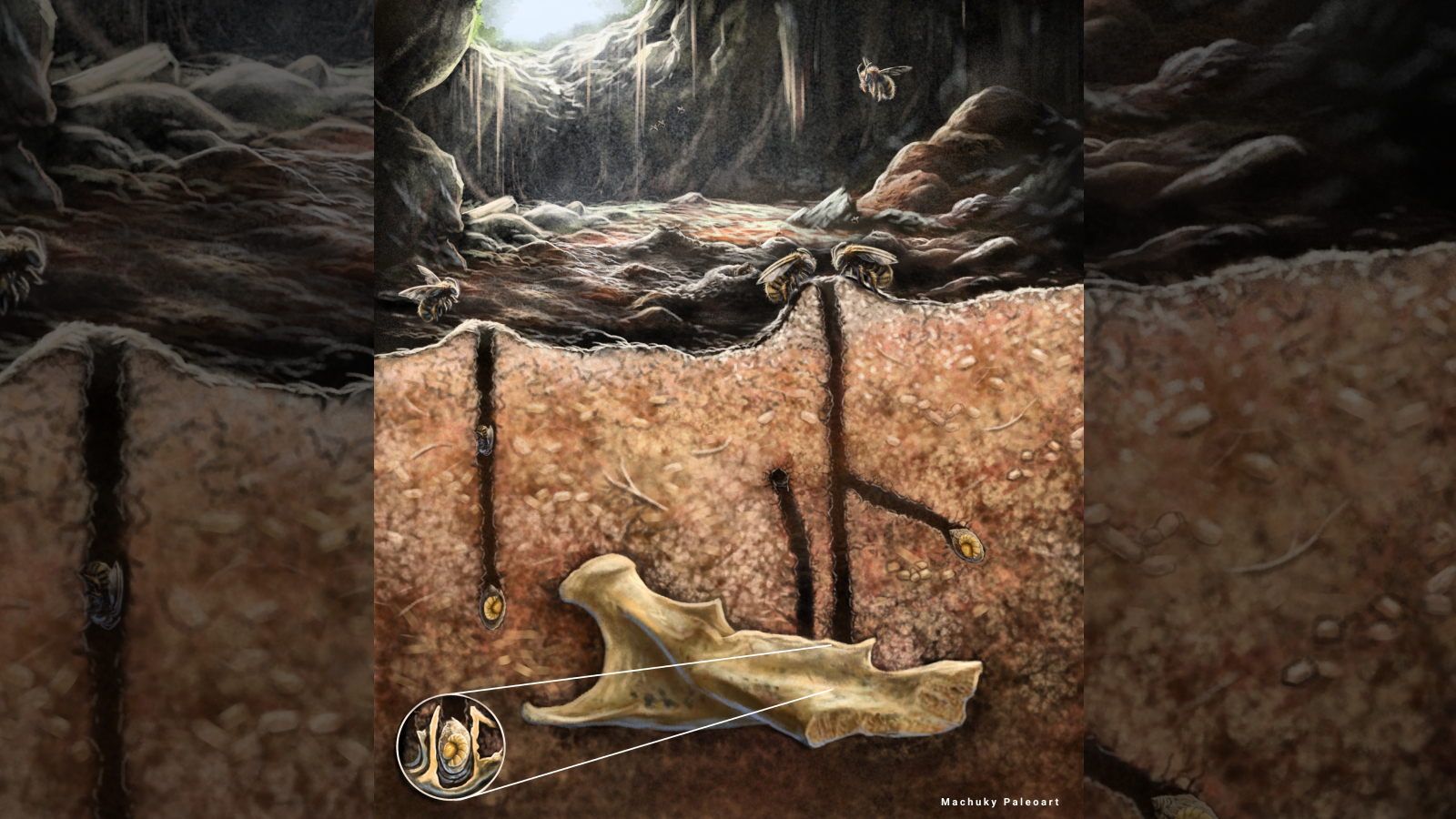

Scientists made a unique discovery in a cave on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola: dozens of fossilized bee nests inside rodent bones that were deposited by owls thousands of years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

More than 5,000 years ago, burrowing bees made their homes inside heaps of rodent bones buried in a cave on Hispaniola, the Caribbean island that comprises the Dominican Republic and Haiti, a new fossil study suggests.

The bees encountered the bones while digging to their preferred depth in the soil. They stopped to build nests inside tooth and vertebra cavities, which turned out to be the perfect size, researchers found. Most of the bones the scientists recovered were from hutias — chunky rodents that look like a cross between squirrels and beavers — but a handful were the remains of an extinct type of sloth.

This is the first time that bee nests have been discovered inside preexisting nooks in fossils and only the second piece of evidence of burrowing bees nesting in a cave. Researchers previously documented examples of bees drilling into old bones to make their nests, but the new find suggests the bees readily settled in existing fossil cavities, according to the study, which was published Wednesday (Dec. 17) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Article continues below"The cells of Osnidum almontei [the name given to the fossilized nests] appear highly opportunistic, filling all bony chambers available in the sediment deposit," the researchers wrote in the study.

The bees found the hutia bones a long time after they were deposited in the cave by Hispaniolan barn owls (Tyto ostologa), the researchers posited. Evidence shows that these owls, which are now extinct, sometimes transported hutias into the cave whole, discarding the bones as they devoured the rodents, and sometimes regurgitated pellets containing the remains of hutias they had eaten while hunting. Barn owl bones found in the cave indicate the species lived there, the researchers noted.

These piles of bones became buried over time as sediments washed into the cave from outside. And several generations of burrowing bees took advantage of this much later, even though these bees typically make their nests in the open, according to the study.

In one tooth cavity, the researchers found six nested bee nests, indicating that successive generations made their homes in the same spot after previous nests had been abandoned.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The bees may have chosen to nest in the cave rather than outside it because the surrounding landscape had little to no earth for burrowing. "The area we were collecting in is karst, so it's made of sharp, edgy limestone, and it's lost all of its natural soils," study co-author Mitchell Riegler, a teaching assistant at the University of Florida, said in a statement.

After one of the scientists' last visits to the cave, plans had been submitted to turn it into a septic storage facility.

"We had to go on a rescue mission and get as many fossils out as possible," study lead author Lazaro Viñola Lopez, a paleobiologist at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, said in the statement.

The plans to build a septic tank eventually fell through, but the scientists removed abundant fossils regardless. These fossils have yet to be analyzed, and the team plans to publish more studies about their finds.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus