3,000-year-old mummified bees are so well preserved, scientists can see the flowers the insects ate

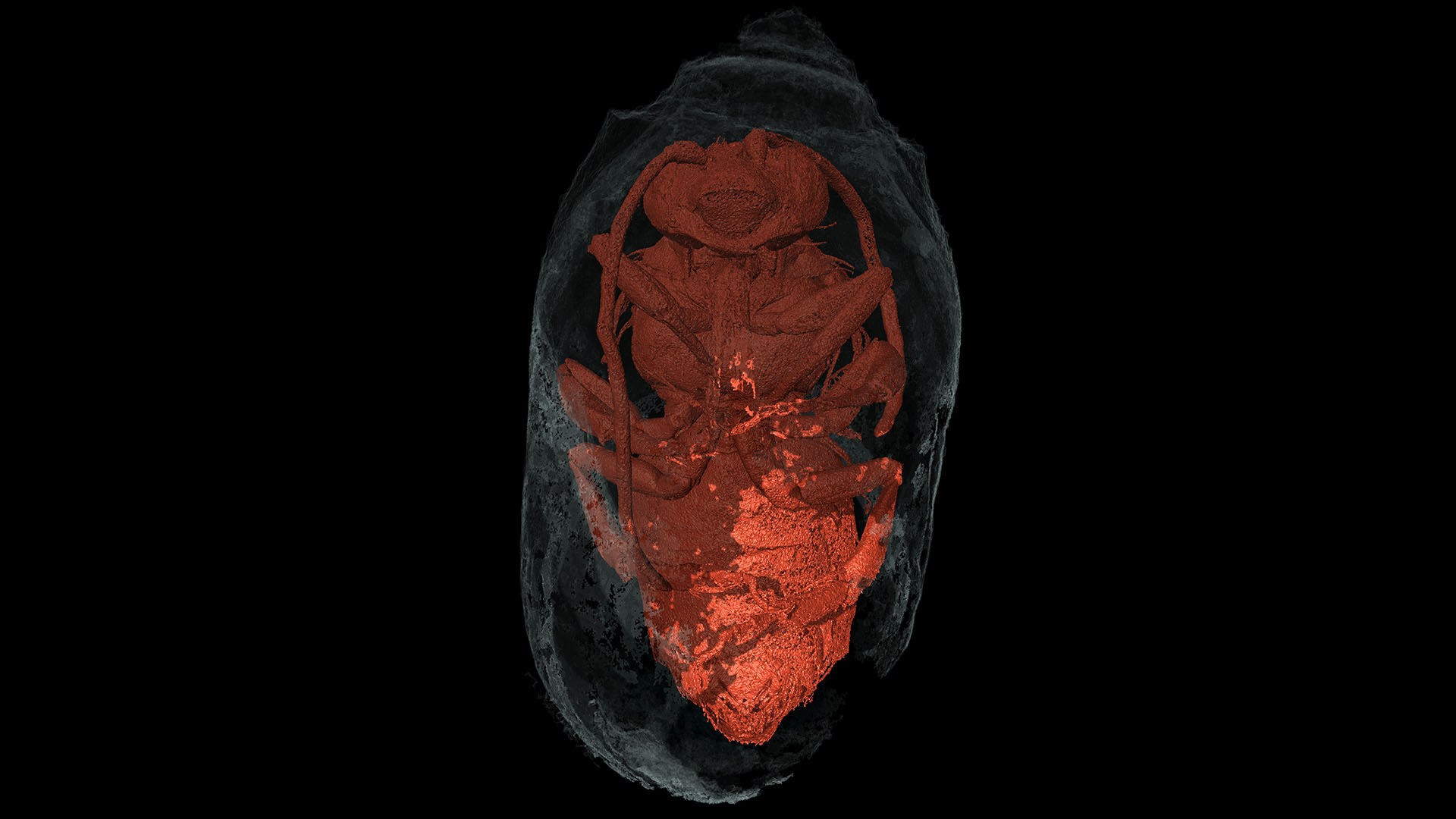

The bees were preserved well enough for researchers to make out small features, like their legs and antennae.

Thousands of years ago, a group of adolescent bees became trapped in cocoons inside their nest and left behind a remarkably preserved record of their "mummified" remains.

Researchers in Portugal reported the discovery of the ancient insects and fossilized bee nest — the first to be found with bees preserved inside it — in a study published July 27 in the journal Papers in Palaeontology.

"This new fossil site is a remarkable opportunity to better understand bee nesting behaviors and their evolution, because we can be face to face with the users of the nests," lead study author Carlos Neto de Carvalho, a paleontologist at the Naturtejo UNESCO Global Geopark in Portugal, told Live Science in an email.

Related: 41 million-year-old insect sex romp preserved in amber

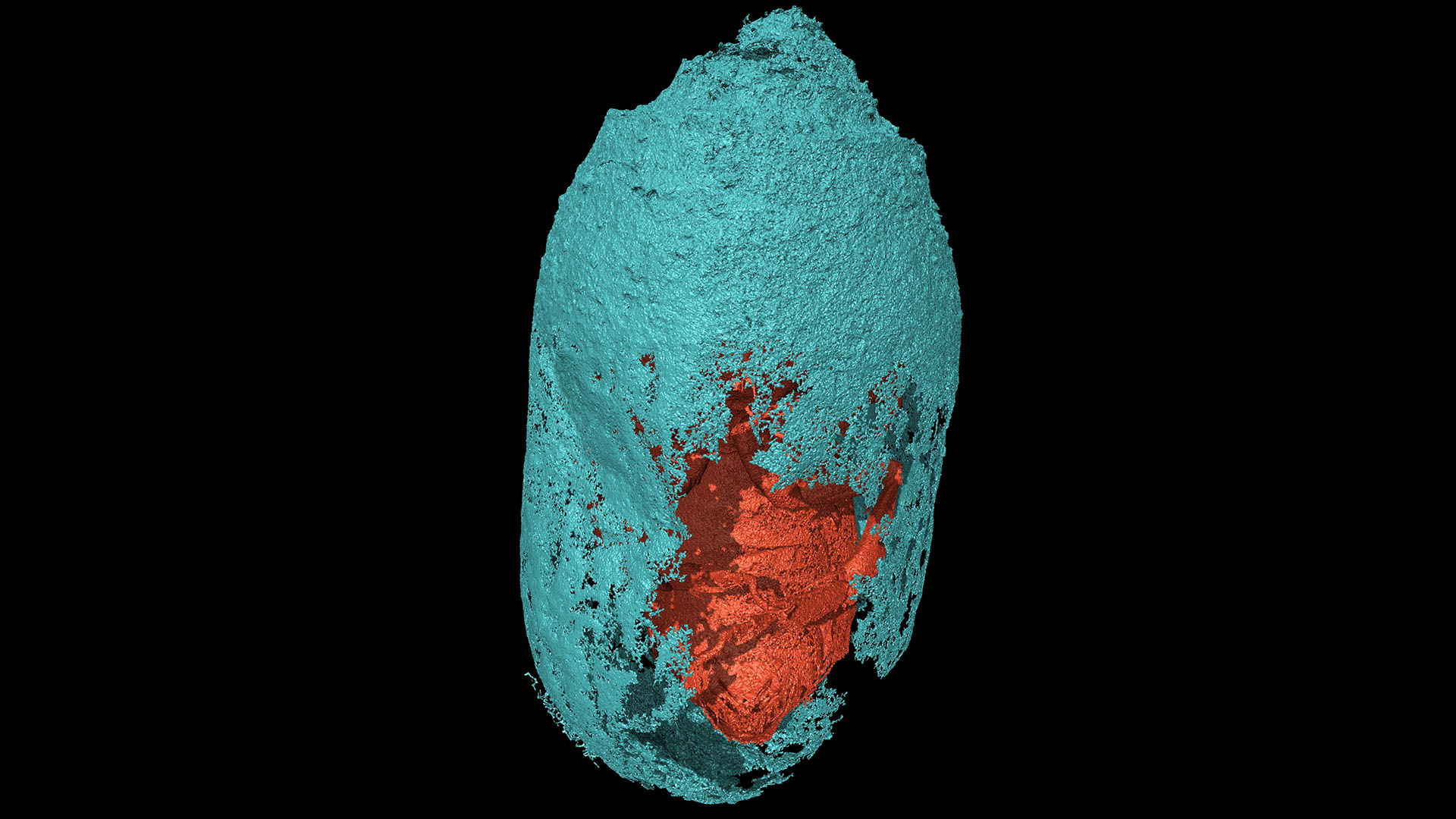

The bees were found in rocks that formed about 3,000 years ago near the Atlantic coast of Portugal. The researchers had found fossils of "bulb-shaped" objects that they identified as traces of ancient cocoons. Because these kinds of burrows could have been dug by many kinds of bees or wasps, however, the researchers assumed they'd never know what created the objects, Neto de Carvalho said — that is, until they found some intact, sealed cocoons.

By scanning these samples, the team could see the remains of ancient bees hidden inside these cocoons, looking remarkably undeformed for having sat underground for thousands of years. The specimens are intact enough that researchers placed them in the tribe Eucerini, a group of bees that often have exceptionally long antennae. The specimens also contain evidence of pollen from a Brassicaceae plant, revealing what these bees might have been eating, Neto de Carvalho said.

These bees lay their eggs in in underground nests, where, over time, their spawn spin cocoons as they develop and grow into adult bees before emerging aboveground. But these individuals were killed before they reached that stage — and killed in a way that might have led to their exceptional preservation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers speculated that all of the bees died at once, potentially by a sudden freeze or by flooding and subsequent burial, Neto de Carvalho said. These conditions could have created a mini-environment around the bees without oxygen, which could have kept away the bacteria that would usually help break down insects' bodies after they die, the study authors proposed.

Well-preserved prehistoric insects are often found in dried amber, when an animal gets caught and encased in sticky tree sap, Bryan Danforth, an entomologist at Cornell University who was not involved with the new research, told Live Science. But even in the rock layer, fossil evidence of insects dates all the way back to the "giant, dragonfly-like creatures" of the Paleozoic era, more than 250 million years ago, he added.

Scientists already knew that bees were living in Portugal 3,000 years ago, but, Danforth said, this study gives us insight into "the ability of fossils to recover aspects of bee behavior and bee life history."

Ethan Freedman is a science and nature journalist based in New York City, reporting on climate, ecology, the future and the built environment. He went to Tufts University, where he majored in biology and environmental studies, and has a master's degree in science journalism from New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus