'We know what to do; we just have to implement it.': Pregnancy is deadlier in the US than in other wealthy countries. But we could fix that.

Cuts to Medicaid and legal confusion around patient care post-Roe v. Wade may prevent improvements in the maternal mortality rate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Jordyn Albright's pregnancy-and-delivery journey was difficult from the start. Her pregnancy was high risk, due to both in vitro fertilization (IVF) and high blood pressure during pregnancy. She was induced three weeks early and went through 60 hours of labor before delivering.

With her son in her arms, the worst should have been behind her. But within moments, her doctor realized her placenta was stuck to her uterine wall. Hospital staff gathered around her, trying to remove the placenta manually — "a horribly painful experience," Albright, 32, said. She wouldn't stop bleeding.

Mere minutes after giving birth, Albright passed out from blood loss. What she didn't hear was her care team calling for a rapid response, which is an alert in labor-and-delivery units that brings an emergency team of doctors and nurses rushing to the room. This team saved Albright's life with 4 pints of blood (she would later need 2 more) and whisked her to emergency surgery to remove the retained placenta.

This harrowing experience was followed by a traumatic few days in the intensive care unit (ICU) and separation from her newborn. It was compounded by weeks in the neonatal ICU for the new baby, who contracted a rare bacterial infection after birth. But Albright and her husband, Jeffrey Albright, credit their care team with saving both mom and child.

"This could have been so much worse," Jeffrey Albright, 32, told Live Science. "In any way you can think of it, it could have been worse."

For too many families, it is worse. A higher percentage of people die in pregnancy, childbirth or the postpartum period in the U.S. than in comparable wealthy countries. It's a problem of health disparities, access to health care, and how individual hospitals handle emergencies — and the problems could deepen with recent policy decisions in the U.S., experts say.

Despite the bleak numbers, there is hope. Evidence suggests that most of these deaths are preventable and that some relatively straightforward interventions could slash the maternal death rate. Those measures include better prenatal monitoring to prevent emergencies in the first place, as well as more training for hospital personnel to react when emergencies do happen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We know what to do," said Jeanne Conry, past president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. "We just have to implement it."

Causes of maternal death

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines maternal mortality as the death of a patient during pregnancy or up to 42 days after delivery from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or pregnancy care. For example, someone who dies in a car wreck during pregnancy wouldn't be counted, but someone with a preexisting heart condition whose condition worsened due to pregnancy would be.

Although maternal death is rare in the U.S., the rate is higher than in other wealthy nations. Provisional CDC data suggest that in 2024, there were 19 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births, compared with 8.4 per 100,000 in Canada, 8.8 per 100,000 in South Korea, 5.5 per 100,000 in the U.K. and zero in Norway, according to The Commonwealth Fund, a health policy foundation.

The U.S. has long been an outlier among its wealthy peers in maternal mortality, even though the country spends about twice as much per person on health care as other large, wealthy nations do, according to the Peterson Center on Healthcare and the health policy organization KFF, a health policy research organization.

"We rank very poorly on the world stage," said Dr. Monique Rainford, an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at the Yale School of Medicine and the CEO and co-founder of Enrich Health, a startup that aims to provide evidence-based prenatal care.

According to The Commonwealth Fund, about half of U.S. maternal deaths happen the day after birth, and about a third occur during pregnancy. During pregnancy, one-third of the deaths are due to stroke and heart conditions, according to the March of Dimes, while emergencies such as hemorrhage cause the most deaths during labor and delivery. Bleeding, high blood pressure (including pregnancy-induced conditions such as preeclampsia, a life-threatening persistent rise in blood pressure that can develop during pregnancy or up to six weeks postpartum), infection and cardiomyopathy (a weakening of the heart muscle) cause the most deaths after delivery.

"What's coming out of our research is that cardiovascular disease is really increasing," Conry told Live Science.

While the U.S. has high rates of certain conditions that increase the risk of complications during pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period — such as obesity — other countries with high rates of these risk factors have much lower rates of death than the U.S.

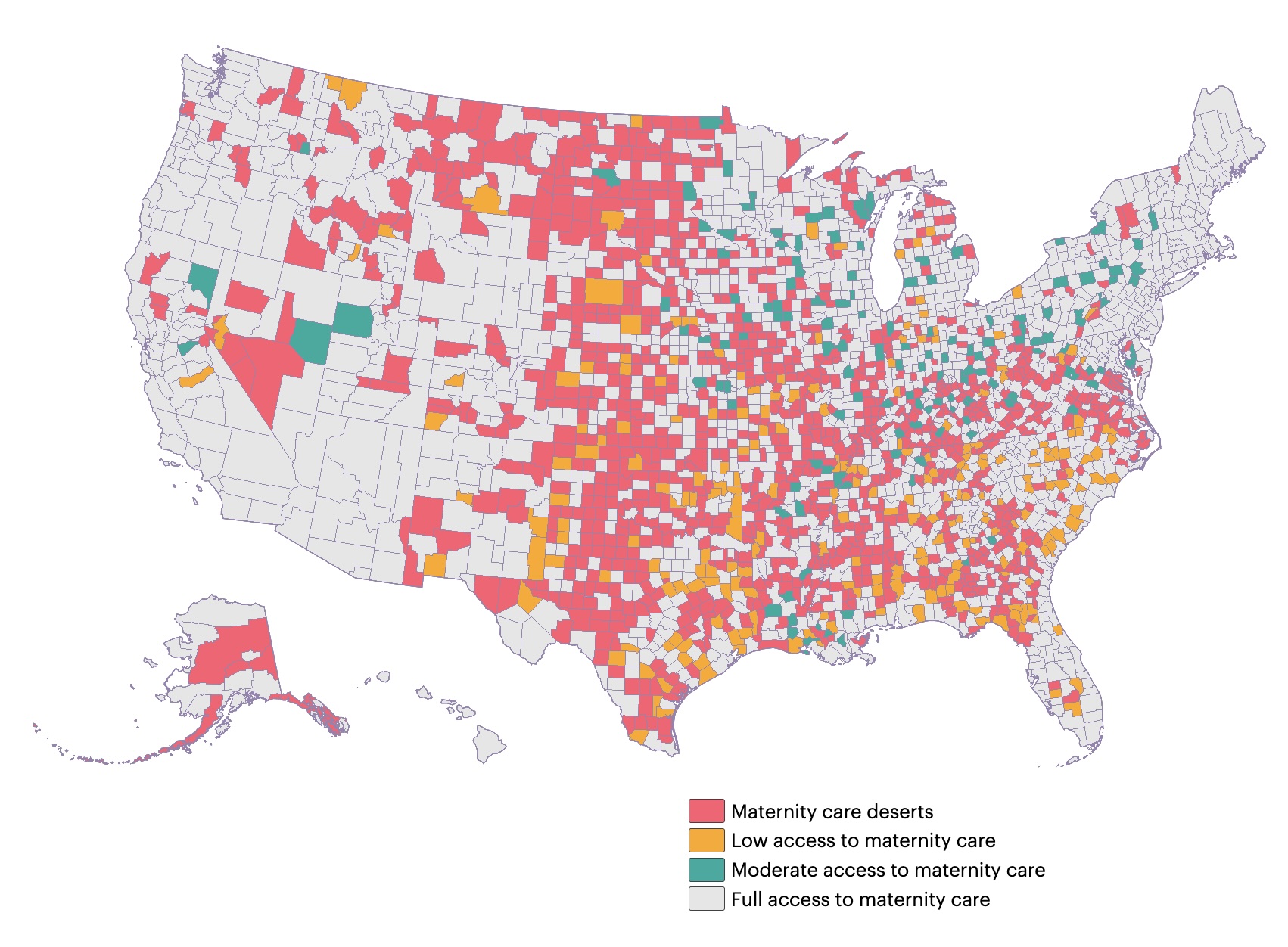

Maternity deserts

One factor in the U.S.' comparatively poor outcomes is that many women live in "maternity deserts" — areas where there is no nearby hospital that offers maternity services or neonatal specialists. Thirty-five percent of counties in the United States are maternity care deserts, according to the March of Dimes.

As of 2022, 52% of rural hospitals did not offer obstetric care, and the problem has worsened since then. According to 2024 research in the journal JAMA, 238 rural hospitals stopped offering obstetrics between 2010 and 2022, and only 26 rural hospitals added obstetrics to their offerings in that time period. (During the same period, 299 urban hospitals lost obstetrics, but 112 added in new offerings.)

In addition, a 2021 study of New Jersey maternity hospital closures found that women had a higher rate of maternal morbidity rate — a measure of serious and life-threatening complications around pregnancy and childbirth — if they gave birth after an obstetrical unit closed in a nearby hospital.

Lack of maternity care is a big problem in rural areas, but it's not exclusively a rural one. Around 35% of urban hospitals lack obstetric care. In addition, other health care access problems can make it difficult for women to get to prenatal appointments where problems can be spotted and managed early on.

Even in dense Chicago, "if your Medicaid provider is not in network, you're a lot of times forced to use public transport in horrible weather, often with other children, to get preventative care," said Star August Ali, a certified professional midwife and the executive director and founder of the Black Midwifery Collective in Chicago, which aims to train and support Black midwives.

Looming cuts

The Medicaid cuts in the "Big Beautiful Bill Act" signed into law in July could spell deep trouble for maternal mortality. The cuts are expected to hit rural hospitals hard, according to KFF, with the likely closure of 144 rural labor and delivery wards.

And about 41% of U.S. births are covered through Medicaid. While it's not clear how the cuts will affect enrollment during pregnancy, without that coverage, people may not have access to treatments and monitoring that could head off some life-threatening emergencies.

The impact of these policies is not equal. Medicaid covers about 28% of births to white mothers, 64% of births to Black mothers, and 67% of births to American Indian or Alaska Native moms. Younger women are also more likely to be covered by Medicaid than by private insurance, with almost 79% of births to moms under age 20 being covered by the government program.

If fewer pregnant women are covered, "we're going to see a huge uptick of emergency room utilization, a huge decrease in preventative care and early detection," during pregnancy, Ali told Live Science.

Racial disparities

The same groups that may lose the most coverage under the Medicaid cuts are also those that are at higher risk of poor outcomes for mom and baby. Black and Native American women are two to three times more likely than white women to die during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period, according to KFF.

Some of this disparity has to do with access to care and poorer quality of care for people of color. A 2025 study of over 3,000 hospitals showed sparser staffing and worse mortality outcomes in hospitals that served predominantly Black patients compared with hospitals with lower percentages of Black patients. And the 2021 study on maternity unit closures also found that severe maternal morbidity was worse in hospitals that served many Black patients.

Research also suggests that American Indian and Alaska Native patients face serious gaps in their health care coverage, which could prevent them from accessing lifesaving preventive care.

Racial bias by health care providers may play a role as well. A 2017 review of studies on doctor-patient communication found that Black patients experienced "poorer communication quality, information-giving, patient participation, and participatory decision-making" compared with white patients. This could lead to a lack of trust between doctor and patient that affects clinical decision-making, the study researchers wrote. For example, the doctor may view the patient as less engaged and fail to give them important recommendations about how to care for their health.

Preventable deaths

Despite big-picture problems with the healthcare system, the data suggest that there are opportunities to prevent a large number of maternal deaths.

"Maternal mortality is a marker of the health of your country."

Andreea Creanga, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

A 2024 study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology looked at deaths across 42 states and found that over 90% of deaths from preeclampsia and eclampsia in the U.S. could have been prevented. So could more than 80% of deaths from hemorrhage and cardiovascular conditions and about 70% of deaths from infection. Harder to prevent are deaths from stroke or amniotic fluid embolism, an emergency in which amniotic fluid enters the maternal bloodstream, but even then, 40% of deaths were found to be preventable.

The fraction of deaths that could have been prevented with immediate improvements in medical care varied dramatically among states, from 45% to 100%, the study found.

"The number one finding is this variability," said study author Dr. Andreea Creanga, a public health researcher at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

That variability is actually a cause for hope, experts say, because it suggests there are clear measures that states, hospitals and providers can implement to reduce maternal mortality.

Learning from each death

The first step in preventing these deaths is to study each death in detail, Rainford said.

States that have studied these deaths and used those lessons to make concerted efforts to reduce maternal mortality have seen success. California's long-running Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, for example, prompted a dramatic decline in maternal mortality in the decade after it was started in 2006, putting the state almost on a par with Canada.

The collaborative helps to investigate the causes of individual deaths, looking for preventable factors. "It's transformed things," Conry said.

But current policies and politics may be hindering efforts to learn from past experiences. After the investigative news organization ProPublica reported a series of preventable maternal deaths in Texas and Georgia likely caused by hospitals delaying care out of fear that doctors would be prosecuted under the states' strict abortion laws, Georgia abruptly fired every member of its committee on maternal deaths. The state will not disclose who is now on the committee. The board in Idaho, which also has a strict abortion ban, was dissolved by state lawmakers in 2023 before being reestablished in 2024, leading to gaps in analysis and methodology changes. Texas' committee skipped analyzing deaths in 2022 and 2023, the two years after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and enabled the state to enact laws restricting nearly all abortions.

The lack of transparency stemming from abortion politics is a barrier to reducing maternal mortality.

Standardizing care

Creating and implementing standards of care is another way to lower death rates. For instance, after the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative analyzed maternal deaths in detail, they found a clear pattern: Too many women were dying of postpartum hemorrhage, one of the most common causes of maternal mortality.

So they provided hospitals tool kits to handle emergency scenarios, including standardized drills, training, and instructions to stock a "crash cart" of supplies to handle postpartum hemorrhage.

The same concept of standardized care could be extended to other conditions beyond hemorrhage, Conry said. For instance, the Collaborative will soon release guidance on better recognizing sepsis, a type of life-threatening infection that can occur during or after childbirth.

There is also a need to improve monitoring before labor and delivery. Over time, the immediate causes of death have been shifting from rapidly-developing emergency situations, such as hemorrhage, toward chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, Creanga said.

This underscores the importance of people receiving regular care through pregnancy and for increased monitoring of high-risk individuals. For example, Johns Hopkins has launched an initiative called The Maryland Maternal Health Innovation Program (MDMOM) that includes at-home, telehealth-supported blood-pressure monitoring for pregnant patients with high blood pressure. That could help catch patients whose health is deteriorating, before an emergency happens. (The Preeclampsia Foundation offers a similar program nationwide.)

Creanga and her colleagues are also working to improve education for health care professionals and community groups around warning signs for high-risk pregnancy. The goal is to get tools into the hands of patients and their families, Creanga said, and to move the U.S. into the company of countries like Norway, where maternal death is vanishingly rare.

"Maternal mortality is a marker of the health of your country," she said. "It's maybe the most important marker."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus