Diagnostic dilemma: Woman had her twin brother's XY chromosomes — but only in her blood

Doctors discovered a woman had "blood chimerism" after examining the chromosomes of cells from different parts of her body.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The patient: A 35-year-old woman in Brazil

The symptoms: The woman was referred to a hospital following a miscarriage at seven weeks of pregnancy. Leading up to the hospital visit, the woman's gynecologist had decided to check the patient's chromosomes to see if there was an underlying genetic reason for the pregnancy loss.

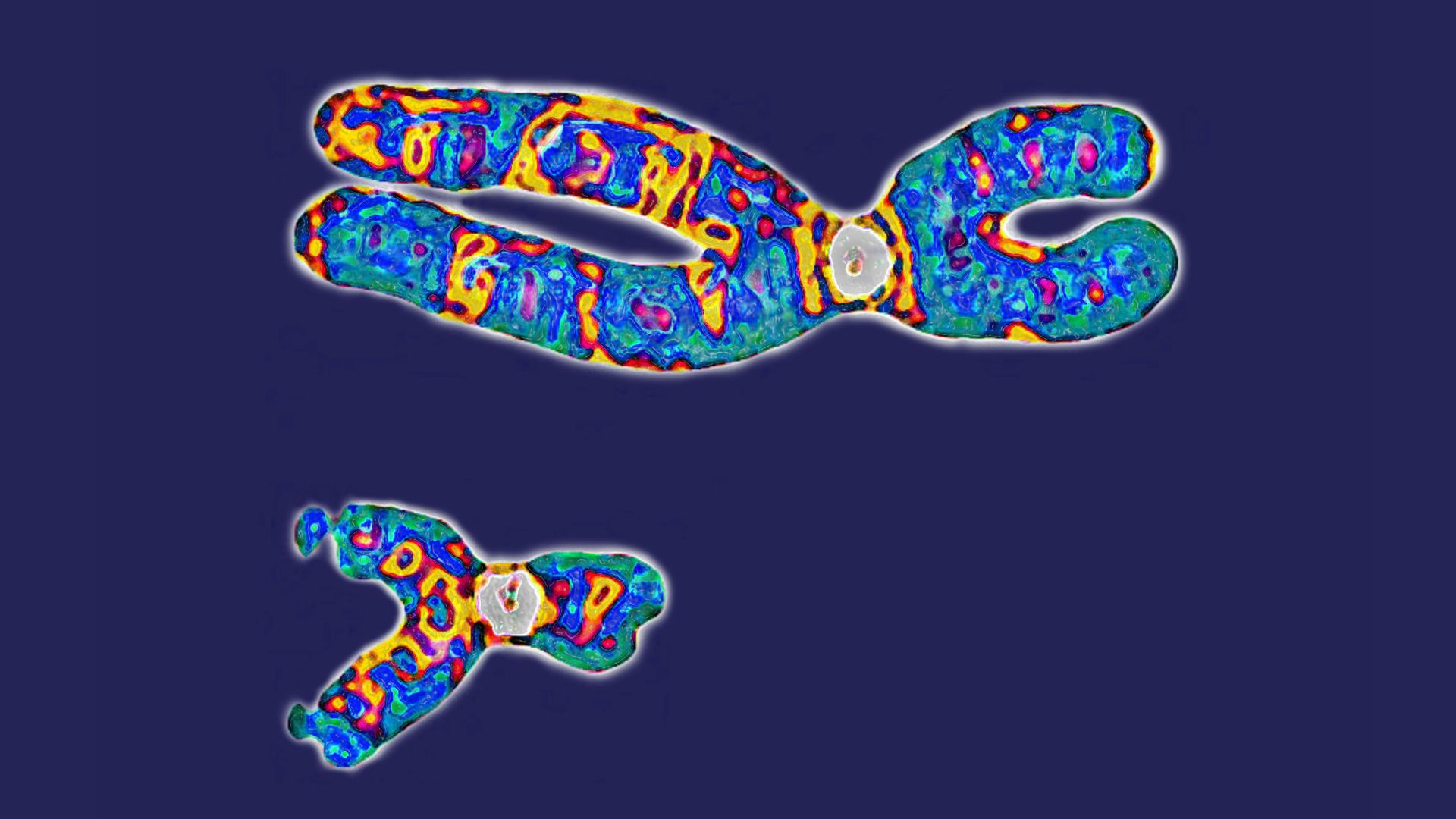

The most common karyotype, or chromosomal profile, for a woman is 46,XX. The 46 indicates 23 pairs of chromosomes in each cell. Two of these are sex chromosomes, which are usually XX for women and XY for men. However, the tests revealed that the patient's karyotype for her blood cells was 46,XY — the typical karyotype for a male.

What happened next: At the hospital, doctors performed two additional blood tests and ordered more tests to examine other chromosomes in the woman's body. Her skin cell karyotype was 46,XX.

The doctors then conducted a physical examination of the patient. Her visible traits were female, and they found no abnormalities in her genitals or reproductive system. Her hormone production was also within the normal range. As an adolescent, her sexual development had been normal, she told the doctors, with regular menstruation that began when she was 13 years old. There were no unusual health incidents in her medical history, and she was the first person in her family to be tested for a potential genetic disorder, the physicians wrote in a report describing her case.

The diagnosis: Doctors identified her condition as chimerism, in which the body contains at least two different sets of DNA across different cells.

This can sometimes happen after a blood transfusion or organ transplant, in which one person receives tissues (and thus DNA) from another individual. But chimerism can also happen naturally, when several fertilized eggs fuse in the uterus to produce a single fetus, or when cells and their DNA are "traded" in the womb. This swap can occur between a mother and an embryo, and sometimes between twins that share the same placenta or whose individual placentas interact in some way.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The patient in this case had a twin brother. When the doctors analyzed samples from the woman's brother and parents, they found genetic variants in the twin brother's XY blood cells that matched those in the patient's blood. They concluded that during fetal development, the woman had incorporated her twin's DNA into her blood cells while still retaining a different copy of DNA with XX chromosomes in the rest of her body's tissues.

"There was a transfusion process that we call feto-fetal transfusion," Dr. Gustavo Arantes Rosa Maciel, a co-author of the report and a professor in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of São Paulo, told BBC News Africa (translated from French). "At some point, the veins and arteries of the two children became intertwined in the umbilical cord."

The outcome: About 11 months after the patient's miscarriage and after she had completed testing at the hospital, the woman became pregnant again. As a precaution due to her prior miscarriage, the doctors prescribed supplements of the hormone progesterone to be given vaginally during the pregnancy. There were no complications, and she gave birth to a healthy boy.

What makes the case unique: In most cases of people with chimerism involving sex chromosomes, their condition carries substantial physical or reproductive issues. This is the first known example of complete blood chimerism in a woman who otherwise had typical female traits, had no health issues and was able to get pregnant. The case suggests that chimerism in humans is not necessarily a barrier to reproduction.

This is also the first case in the medical literature of a patient becoming a chimera in the womb via her twin's blood, according to the report.

And notably, even the karyotyping test for identifying the woman's condition is not commonly performed. It is not part of a standard medical visit. Therefore, it is unknown how common it is for individuals to carry hidden chromosomal anomalies, and incidences of blood chimerism are likely underreported as a result, the authors wrote. Indeed, studies have suggested that other types of chromosomal variations, such as having extra sex chromosomes, are also underreported.

For more intriguing medical cases, check out our Diagnostic Dilemma archives.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus