Trees in Panama's tropical forests are growing longer roots in the face of drought

A long-term experiment reveals tropical forests in Panama are able to adapt to droughts, but scientists warn this short-term "rescue strategy" is unlikely to save them from the impacts of climate change.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When drought hits, tropical forests in Panama have a "rescue strategy" to adapt to the lack of water by sending their roots deeper underground, a new study has found. But scientists warn this may not be enough to save them from the ravages of climate change.

Tropical forests are home to more than half of the world's terrestrial biodiversity and store large quantities of global carbon. A lot of this carbon is held in their roots below ground. However, climate change is pushing up temperatures in these forests and is expected to bring extreme droughts.

In a new study, published Nov. 21 in the journal New Phytologist, scientists investigated what happens to the roots of trees in tropical forests when they are deprived of water for a long time.

Article continues belowThe results are part of the Panama Rainforest Changes with Experimental Drying (PARCHED) experiment, in which scientists set up 32 plots in four different areas in Panama's tropical forests. Each of the four forests has distinct characteristics, such as tree species, soil nutrient availability and rainfall.

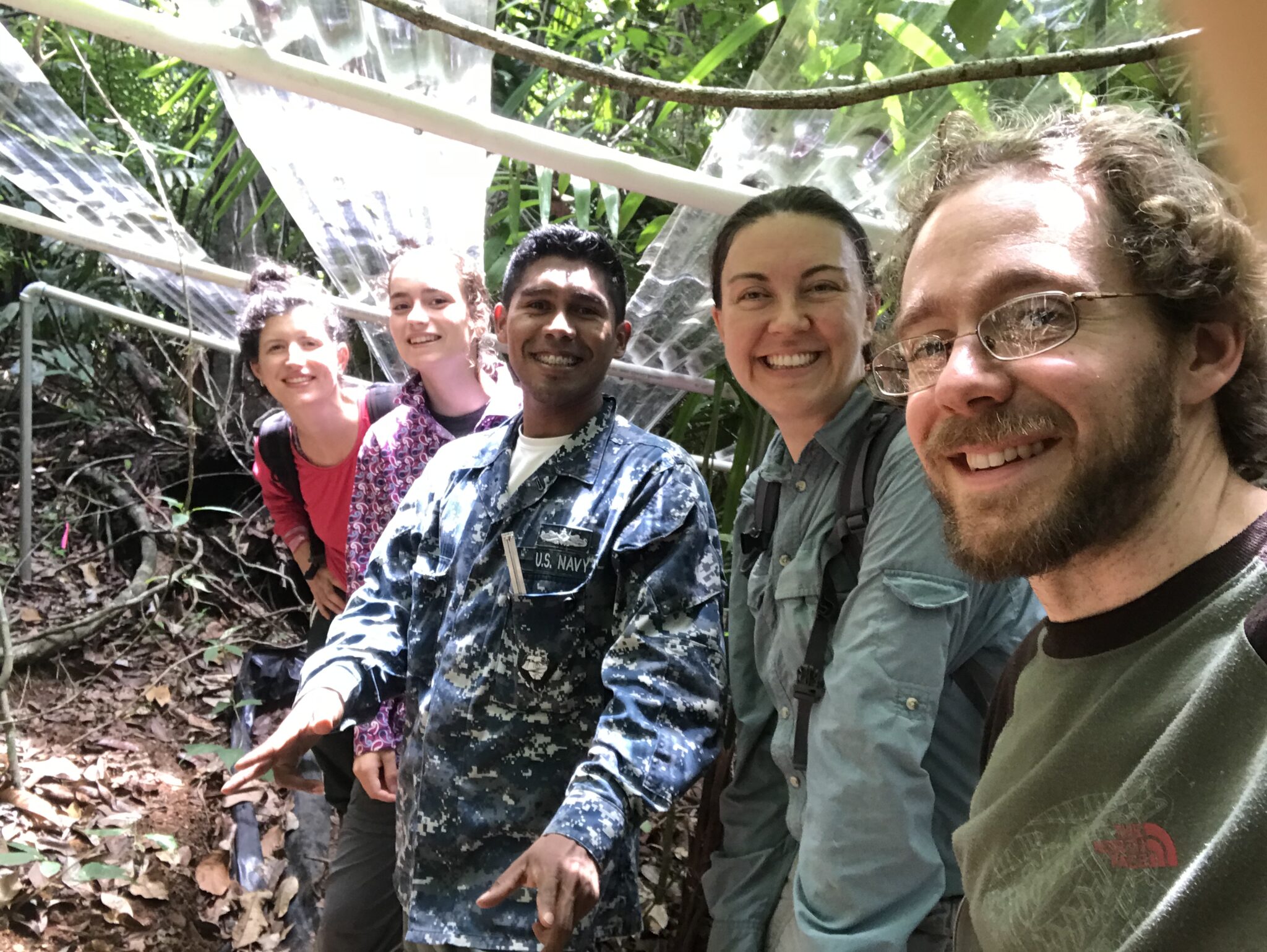

The scientists erected clear roof structures above the plots that excluded 50% to 70% of the rainfall from reaching the forest floor. The structures "look like partial greenhouse roofs," study co-author Daniela Cusack, an ecosystem ecologist at Colorado State University, told Live Science. She has been leading the PARCHED experiment since 2015. The researchers also dug trenches around the plots, which they lined with thick plastic so that the roots could not access water from outside the plots.

The researchers used three methods to find out what was happening with the trees' roots.

They sampled soil cores four times a year for five years. The cores extended about 8 inches (20 centimetres) below the surface. The researchers also had root traps, which are mesh columns filled with soil. Every three months, they checked how many roots had grown into these columns.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The third method involved using small cameras to watch how the roots grew. When the PARCHED experiment was set up, the researchers sank acrylic tubes about 4 feet (1.2 meters) into the ground. These tubes have gaps at regular intervals with cameras looking into the soil.

All four forests, despite being different from each other, showed similar responses to a slowly drying environment.

Chronic drying significantly reduced the quantity of fine surface roots, reducing water and nutrient availability, but the trees had a number of strategies to survive a chronic drought.

"The trees compensated for the surface-root dieoff by sending fine roots down deep into the soil, presumably for moisture acquisition," Cusack said.

"It's not enough root growth to compensate for the carbon or biomass loss," she said. It's more like a "rescue strategy for trees to maintain their hydraulics and physiological function."

At the same time, surface roots were more likely to be colonized by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. This type of fungi forms a symbiotic relationship with plants and increases the availability of water and nutrients.

The remaining surface roots appear to attract more of these fungi to improve their access to nutrients, Cusack said.

Daniela Yaffar, who was not involved in this research but studies roots in tropical forests at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the U.S., welcomed the study but said that more research was needed to understand how roots behaved in other tropical forests.

"While some species have long been adapted to drier environments, these adaptations typically evolve over extended periods," she told Live Science. "The emerging challenge is that tropical forests, especially in regions unaccustomed to such dry conditions, may experience significant shifts and not enough time to adapt."

Species that are less able to adapt to more extreme droughts may decline or disappear from the ecosystem, she said.

—

—

—

Cusack warned that the root adaptation was not a bulwark against climate change. "Our five-year study is pretty short in terms of the lives of tropical forests," she said. "We don't know how long the forest can sustain these adaptations."

Lead author Amanda Cordeiro, a researcher at the University of Minnesota, who was a PhD candidate at Colorado State University during the study, told Live Science the next steps will be to assess the long-term consequences of the root changes, and how it impacts the overall ecosystem in terms of carbon storage and plant fitness. "For example, it is currently unclear whether increased deeper root production can help tropical forests withstand ongoing chronic drying beyond a few years," she said.

Sarah Wild is a British-South African freelance science journalist. She has written about particle physics, cosmology and everything in between. She studied physics, electronics and English literature at Rhodes University, South Africa, and later read for an MSc Medicine in bioethics.

Since she started perpetrating journalism for a living, she's written books, won awards, and run national science desks. Her work has appeared in Nature, Science, Scientific American, and The Observer, among others. In 2017 she won a gold AAAS Kavli for her reporting on forensics in South Africa.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus