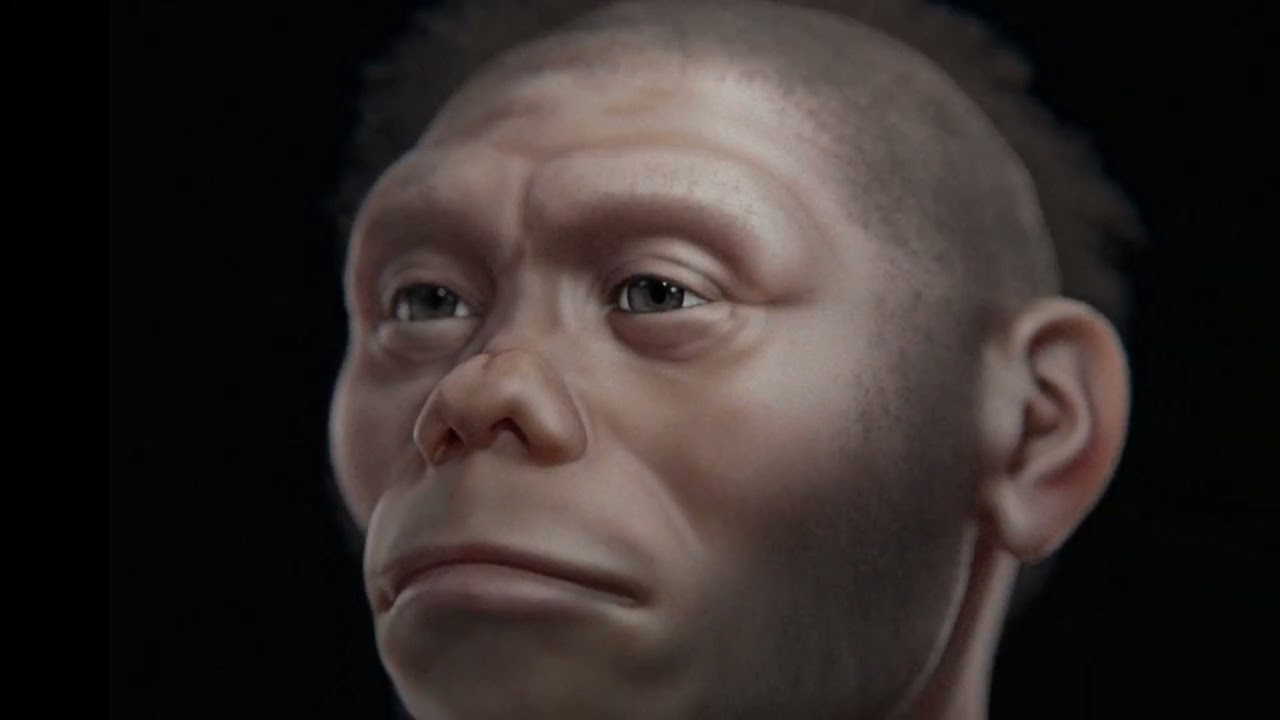

See the face of the 'Hobbit,' an extinct human relative

A new facial approximation offers insight into one of humankind's extinct relatives, Homo floresiensis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In 2003, archaeologists discovered human-like skeletal remains inside a cave in Indonesia. Upon closer inspection, they determined that the individual — most likely female — had an abnormally small head and was of short stature, standing only 3 feet, 6 inches (106 centimeters). Due to the individual's hobbit-like characteristics, which differed from those of known hominins, researchers classified the individual as Homo floresiensis, a smaller offshoot of Homo erectus, an extinct human ancestor.

Now, a new facial approximation offers a glimpse of what this individual, nicknamed "the hobbit," may have looked like when it lived on the Indonesian island of Flores approximately 18,000 years ago.

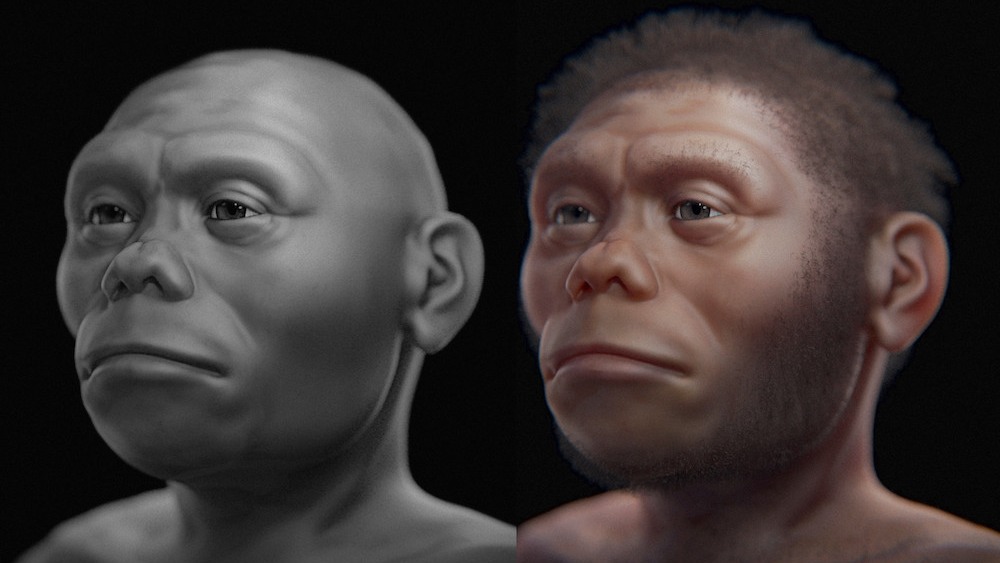

When creating facial approximations, forensic artists often rely on a blend of scans of the individual skull and data points collected from human donor skulls to conduct a process known as "positioning of soft tissue thickness markers," which involves placing a series of small pins that correspond to the topography of the skin on the skull. This provides an idea of a face's general structure, according to a study published online on June 6.

However, because the specimen is of H. floresiensis and not of a modern human (Homo sapiens), there are not many comparable skulls to choose from. So researchers compared computed tomography (CT) scans of the well-preserved hobbit skull with scans of a male H. sapiens skull and scans of a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) skull.

Related: Hobbits and other early humans not 'destructive agents' of extinction, scientists find

"We deformed [both] to adapt them to the structure of the skull of H. floresiensis and interpolated the data to get an idea of what [the hobbit's] face could look like," study co-researcher Cícero Moraes, a Brazilian graphics expert, told Live Science in an email. "The [hobbit] skull is almost complete, missing small parts in the region of the glabella (the part of the forehead directly between the eyebrows) and nasal bone, but fortunately it was possible to design them with the help of anatomical deformation."

Because the specimen's skull was virtually deformed and then was combined with another species — the chimps — the sex from the human database was no longer important, Moraes said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers created two final facial approximations. The first is a neutral black-and-white image of an ape-like individual with a broad nose, and the second is a more stylized version with facial hair.

"Roughly speaking, H. floresiensis probably had a less protruding nose than modern men, the mouth region was a little more projected than ours and the brain volume was significantly smaller," Moraes said. "The final appearance surprised us a lot, because when looking at the face, we can see a series of compatibility with modern men, but not enough to consider her as one of the group."

Gregory Forth, a retired professor of anthropology at the University of Alberta who was not involved in the new research, thinks the facial approximation is a good way to help the public better understand an ancient human relative.

"As described, techniques of anatomical deformation appear to offer benefits for ongoing studies of Homo floresiensis," Forth, author of "Between Ape and Human: An Anthropologist on the Trail of a Hidden Hominoid" (Pegasus Books, 2022), a book about H. floresiensis, told Live Science in an email. "Not only do they provide a method for creating more lifelike images of the morphologically primitive hominin to engage the general public; they potentially reveal new information about the species and its relationship to other hominids."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus