Never-before-seen cousin of Lucy might have lived at the same site as the oldest known human species, new study suggests

An unidentified early hominin fossil that might be a new species confirms that Australopithecus and Homo species lived in the same region of Africa in the same time frame.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

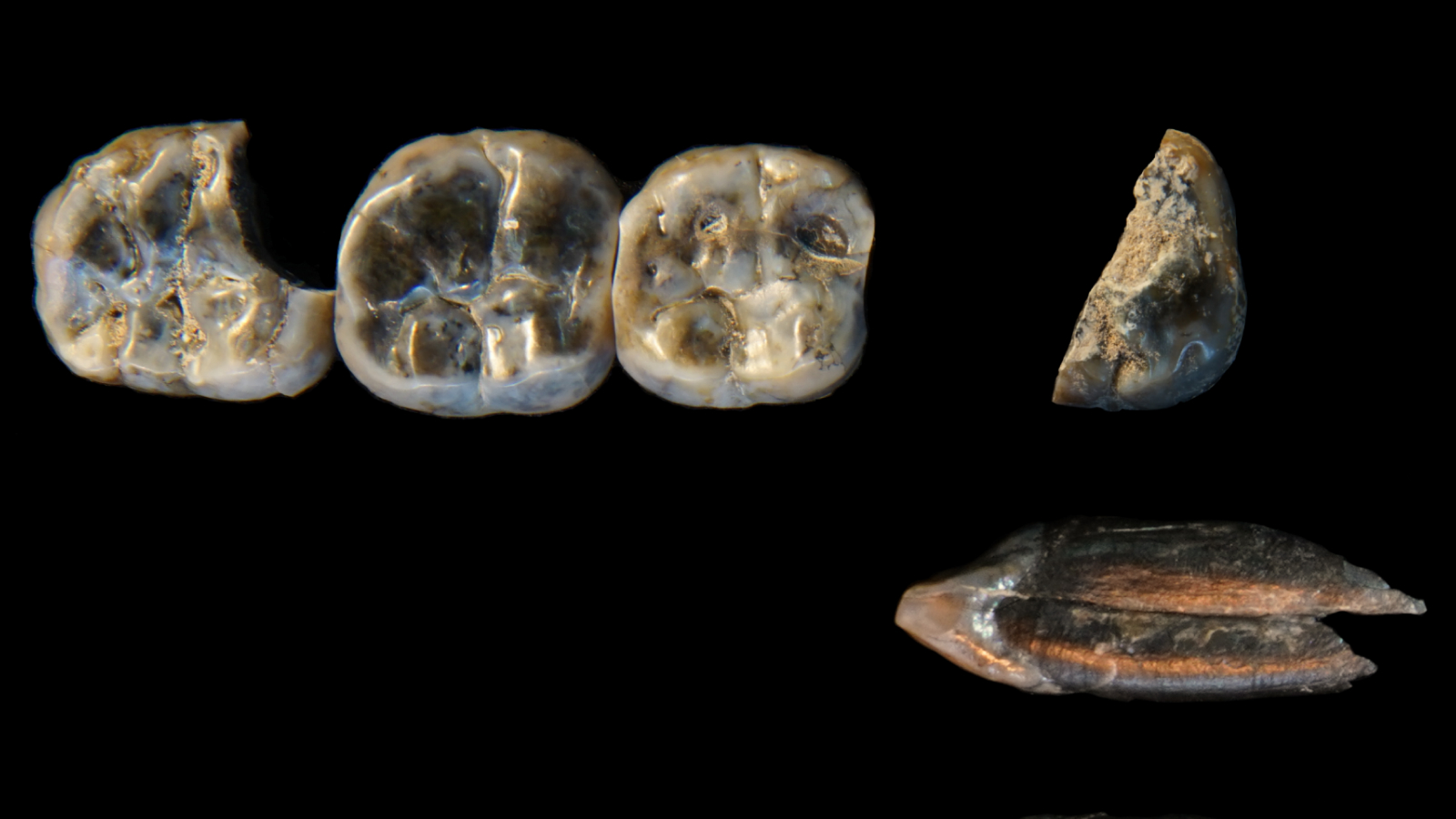

Roughly 2.6 million-year-old fossilized teeth found in Ethiopia might belong to a previously unknown early human relative, researchers say.

The teeth are from a species of Australopithecus, the genus that includes Lucy (A. afarensis). But these newly discovered teeth don't appear to belong to any known species of Australopithecus, according to a new study published in the journal Nature on Wednesday (Aug. 13).

What's more, at the same site the researchers found extremely old teeth from Homo, the genus that includes modern humans (Homo sapiens). These teeth may belong to the oldest known Homo species on record, which scientists haven't yet named, the study found.

These new discoveries show that at least two lineages of early hominins — a group that includes humans and our closest relatives — coexisted in the same region around 2.6 million years ago, the researchers said.

Discoveries at Ledi-Geraru archaeological site

The researchers found the teeth at the Ledi-Geraru archaeological site in northeastern Ethiopia, which is known for earlier groundbreaking discoveries: a 2.8 million-year-old jawbone that's the oldest known human specimen, as well as some of the oldest known stone tools made by hominins, which date to 2.6 million years ago.

Paleontologists and archaeologists hypothesize that the region was an open and arid grassy plain during this period, based on grass-eating animal fossils from that time. The area offered resources Homo and Australopithecus could use, Frances Forrest, an archaeologist at Fairfield University in Connecticut who was not involved with the new research, told Live Science in an email. Grasslands and rivers would have provided water to drink, plants to eat and large animals to hunt.

Related: 'Huge surprise' reveals how some humans left Africa 50,000 years ago

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the unusually rich fossil record in this area could also be because of excellent preservation of remains, due to volcanic eruptions, for example — not necessarily that this was a hominin hotspot, Forrest said.

Australopithecus and Homo teeth

In the new study, the researchers used layers of volcanic ash above and below the newly discovered fossils to determine their age. Of the 13 teeth discovered, the team found 10 are 2.63 million years old and belonged to an unidentified species of Australopithecus, which for now the researchers are calling the Ledi-Geraru Australopithecus.

Previously, researchers had found remains in the region from A. afarensis and Australopithecus garhi. But the newfound teeth look different from the teeth of those species. "It doesn't match any of these, so it could be a new species," study co-author Kaye Reed, a paleoecologist at Arizona State University, told Live Science.

However, the research team hasn't officially named it as a newly identified species because the teeth don't have any especially unique features. "In the fossil record, researchers usually define a new species by finding anatomical traits that consistently differ from those of known species," Forrest said, adding that the evidence from this discovery is too limited to define a new species.

The researchers also identified two teeth that are 2.59 million years old, and one that is 2.78 million years old, all belonging to the genus Homo, which Reed believes are from the same species as the oldest known Homo specimen — the jawbone discovered in Ledi-Geraru — although this hasn't been confirmed.

Study authors J. Ramón Arrowsmith and Christopher J. Campisano examine the geology of the area near the new fossils.

An aerial view of the Ledi-Geraru excavation site, home of the newly discovered fossilized teeth, and where the oldest known Homo specimen has been uncovered.

The new discovery means at least three hominin species were living in this region of Ethiopia before 2.5 million years ago: the Homo and Australopithecus species these teeth belong to, as well as A. garhi.

At the same time, A. africanus lived in South Africa, and Paranthropus, another hominin genus, lived in what is now Kenya, Tanzania and southern Ethiopia.

This evolutionary trial-and-error within the extended hominin family is why humans' evolutionary tree is considered "bushy" rather than linear.

"It has become clear over the last decade or so that during most of our evolutionary history … there have been multiple species of human relatives that existed at the same time," John Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was not involved in the new research, told Live Science. "The new paper tells us this is happening in Ethiopia … [in] a really interesting time frame, because it's maybe the earliest population of our genus Homo."

Next steps

The research team is now studying the enamel on the newfound teeth, as their chemistry can reveal what these species were eating. This may shed light on whether these hominins were eating the same things and competing for similar resources.

"Right now, we can say very little with certainty about direct interaction between Australopithecus and Homo," Forrest said. "We know that both genera sometimes overlapped in time and space, but there is no behavioral evidence linking the two."

Chimpanzees and gorillas live in some of the same forests, Hawks pointed out, but they're mostly geographically separated from each other, not living side by side. The fact these early hominins may have lived closer together than primates typically do now is interesting, Hawks said.

"They probably weren't eating the same things," Reed noted. "But right now we don't really know."

The researchers are also searching for more information and fossils at the site. "Everything we find is a piece in the puzzle of human evolution," Reed said.

Human evolution quiz: What do you know about Homo sapiens?

Olivia Ferrari is a New York City-based freelance journalist with a background in research and science communication. Olivia has lived and worked in the U.K., Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia. Her writing focuses on wildlife, environmental justice, climate change, and social science.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus