Science history: Anthropologist sees the face of the 'Taung Child' — and proves that Africa was the cradle of humanity — Dec. 23, 1924

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Milestone: "Taung Child" skull revealed

Date: Dec. 23, 1924

Where: Taung, South Africa

Who: Raymond Dart's anthropological team

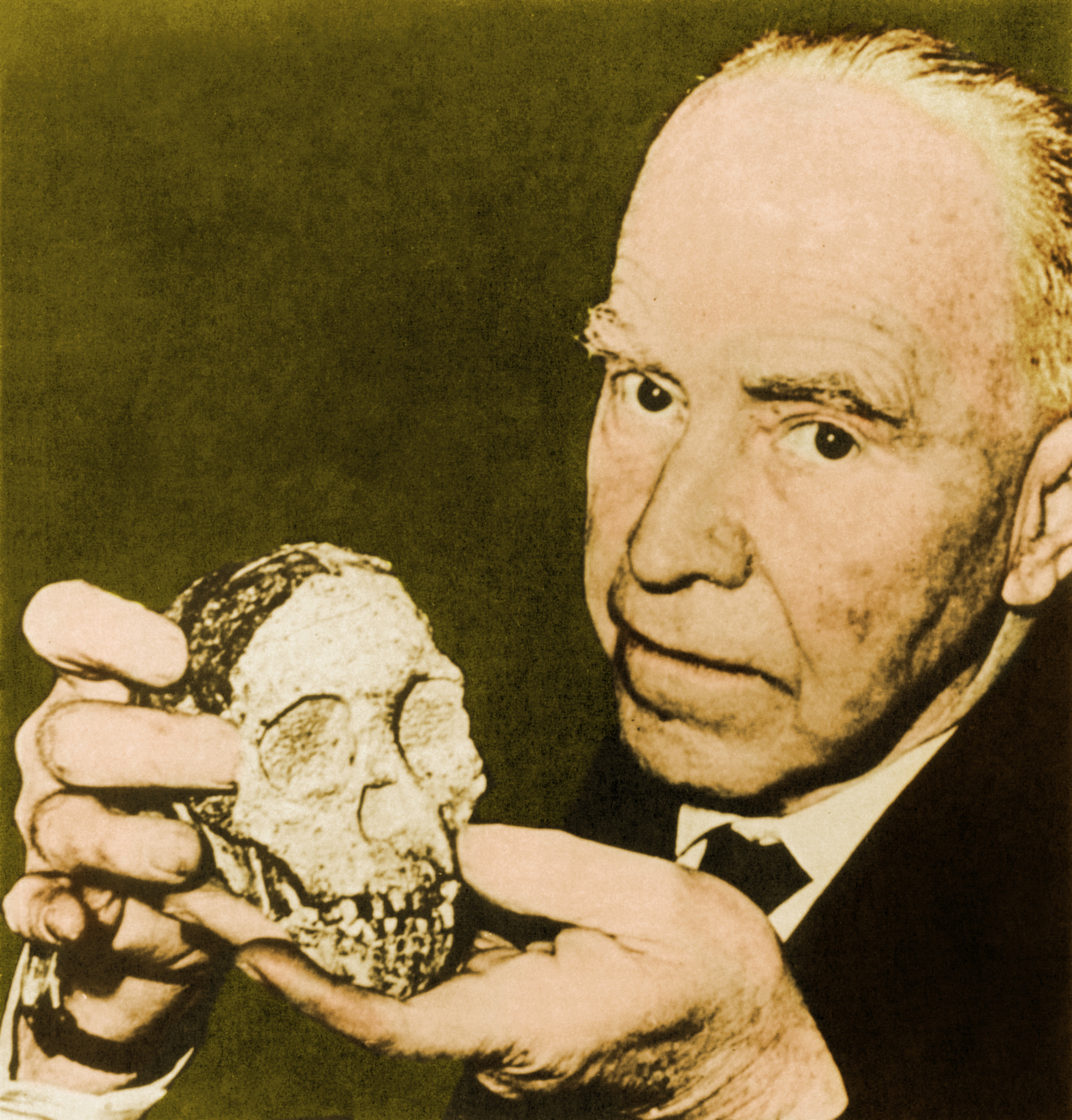

At the end of 1924, an anthropologist began chipping away rock around an old primate skull — and rewrote the story of human evolution.

The diminutive skull — about the size of a coffee mug — clearly belonged to a creature very different from us and yet also quite distinct from other apes and monkeys.

But the man credited with its discovery, Raymond Dart, a professor of anatomy and anthropology at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, hadn't actually excavated the skull.

Rather, it came to Dart because his student had brought another skull from a quarry to his class. Local workers at the Buxton Limeworks in Taung had previously blasted a baboon skull out of the rock and had brought it to the attention of the company. From there, the baboon skull landed with Dart's student, Josephine Salmons. She recognized it for what it was and brought it to his class.

Dart was excited about the possibility that other ancient primate fossils would be embedded in the same sediments, and he showed the baboon skull to his geologist colleague Robert Young. Young knew the quarry and made contact with the quarryman, a Mr. de Bruyn, and asked him to keep an eye out for more skulls. In late November, de Bruyn identified a brain cast in a piece of rock and set it aside for Young, who then hand-delivered the cranium to Dart.

In his 1959 memoir, "Adventures with the Missing Link," Dart makes no mention of Young hand-delivering the skull. Instead, he implies that he had pulled the skull out of rubble in crates that were delivered from Buxton Limeworks.

In Dart's telling, he immediately recognized what he had found.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"As soon as I removed the lid a thrill of excitement shot through me. On the very top of the rock heap was what was undoubtedly an endocranial cast or mold of the interior of the skull," Dart recounted in his memoir. "I stood in the shade holding the brain as greedily as any miser hugs his gold … Here, I was certain, was one of the most significant finds ever made in the history of anthropology."

On Dec. 23, "the rock parted. I could view the face from the front, although the right side was still embedded," Dart wrote in his 1959 memoir.

Over the next 40-odd days, he feverishly analyzed the skull. In a paper published in the journal Nature on Feb. 7, 1925, he described a newfound human ancestor and named it Australopithecus africanus, or "The Man-Ape of South Africa."

The "Taung Child" would rocket Dart to fame and confirm Charles Darwin's hypothesis that humans and nonhuman apes shared a common ancestor that evolved in Africa.

The discovery of the "Taung Child" was the first time scientists had ever found a near-complete fossil skull of an ancient human ancestor. It was longer than other primate skulls, and the molars in the skull suggested "it corresponds anatomically with a human child of six years of age," according to the study, though later estimates would suggest the child died at around age 3 or 4. We don't know for sure, but most researchers think the Taung Child was a girl.

Because the skull was taken out of its "context," it was difficult to peg its age. Over the years, some researchers have estimated it to be 3.7 million years old, but more recent research suggests it was around 2.58 million years old.

For nearly 50 years, A. africanus was thought to be our direct human ancestor. Then, in 1974, scientists digging in Afar, Ethiopia, unearthed another fossil skull from a related species. This one, dated to 3.2 million years ago, was the iconic "Lucy," and her species, Australopithecus afarensis, wound up dethroning the Taung Child as our direct common ancestor.

But there's a twist ending to this story, as scientists found a few fossil fragments that raise the possibility that Lucy's species isn't our direct ancestor after all, with some even suggesting A. africanus could regain its title.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus