A coffin holding a dead 'princess' fell from an eroded cliff over 100 years ago — archaeologists just solved a major mystery about her

Dendrochronological analysis of a mysterious log coffin that tumbled from a cliff a century ago reveals clues to life in Roman-era Poland.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A long-standing mystery about when an ancient European "princess" buried in a log coffin died has finally been solved, a new study reports.

The woman's wooden coffin was initially found in the village of Bagicz in northwestern Poland in 1899, after it fell from an eroding cliff. Archaeologists nicknamed her the "Princess of Bagicz" because of her unique burial style and well-preserved artifacts. Over the decades, researchers determined that she had died in Roman times, but analyses gave conflicting dates spanning nearly 300 years.

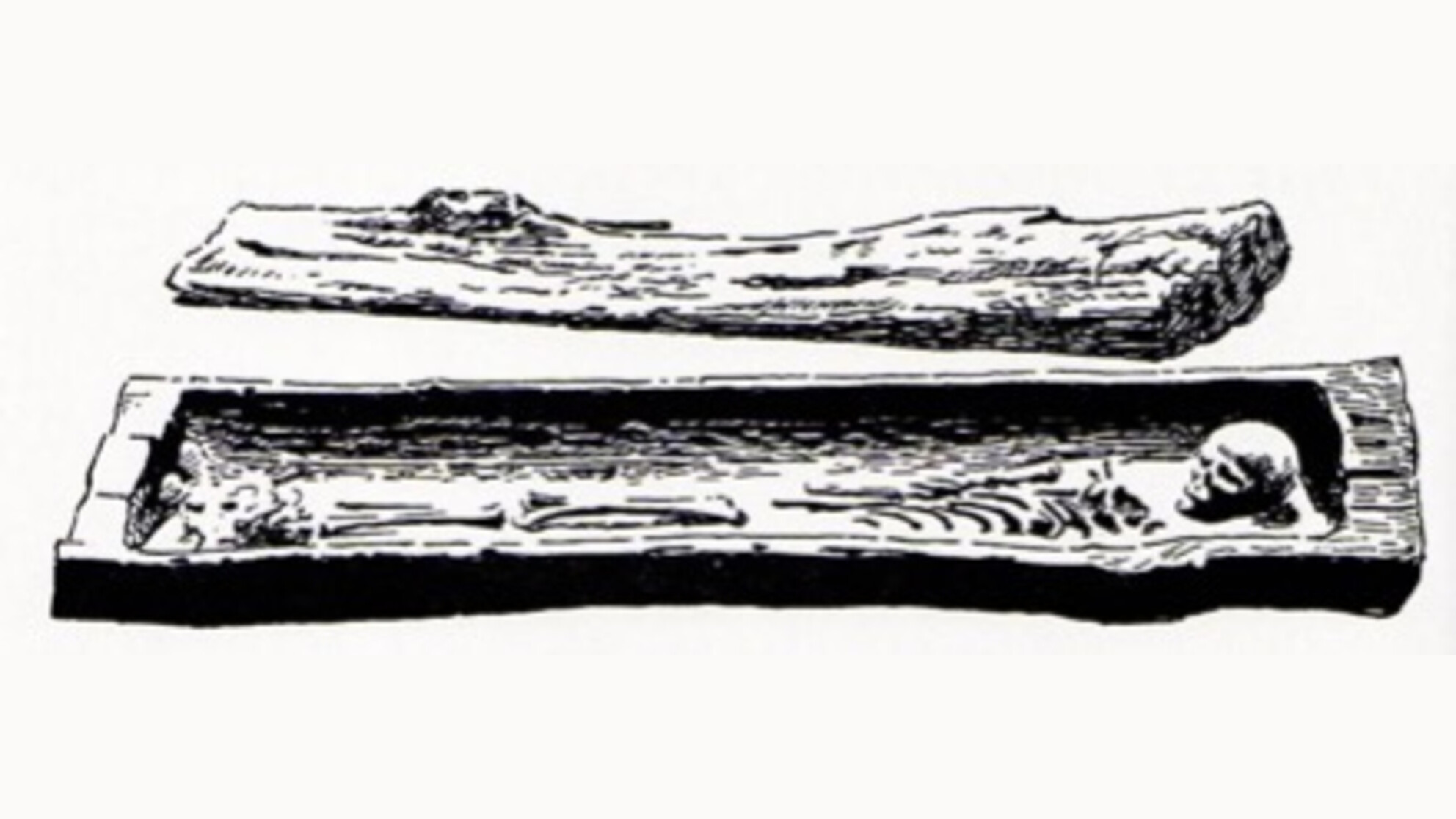

Log coffins are rarely discovered in archaeological excavations, since they disintegrate over the years. The one found in Bagicz is the only preserved wooden sarcophagus of its kind from the Roman Iron Age, researchers wrote in a study published Feb. 9 in the journal Archaeometry. The Bagicz burial is exceptional, the researchers wrote, because the coffin and lid were carved from a single tree trunk. The coffin likely survived into modern times thanks to its location in a wet, humid environment.

Inside the coffin, which came from a larger cemetery associated with the Wielbark culture related to the Goths, was the skeleton of an adult woman who was buried on a cowhide along with a bronze pin, a necklace of glass and amber beads, and a pair of bronze bracelets.

An archaeological examination of the style of the grave goods in the 1980s suggested that the Princess of Bagicz died between A.D. 110 and 160. But in 2018, a carbon-dating analysis of the woman's tooth produced a date of between 113 B.C. and A.D. 65, which would make her significantly older than the artifacts buried with her.

To resolve this discrepancy, a team of researchers led by Marta Chmiel-Chrzanowska, an archaeologist at the University of Szczecin in Poland, dated the log coffin itself using dendrochronological analysis, which involves counting the tree's rings. They collected a small core of wood from the coffin and compared the growth rings to established chronological sequences from northwest Poland.

"The estimated felling date of the oak used for the coffin was calculated as 120 AD," the researchers wrote in the study. "It is likely that the coffin was crafted immediately after felling."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Given that the woman's grave goods and coffin are from the same time period, the radiocarbon date from her tooth is likely incorrect, the researchers concluded, and it was potentially thrown off because of the woman's diet or the water sources she drank from during life.

Radiocarbon dates can be thrown off by up to 1,200 years if the organic sample comes from a marine organism rather than a terrestrial one, scientists have learned, because the carbon stored in the oceans is older than the carbon found on land. This is known as the marine reservoir effect and results in marine organisms appearing to be older than they actually are when they are carbon dated. Similarly, eating a significant amount of seafood can throw off a human's carbon date by dozens or hundreds of years. This might have happened in the case of the Princess of Bagicz.

"The burial provides rare insight into wooden coffin preservation in the Wielbark culture, offering valuable data on funerary practices and environmental conditions that allowed for the exceptional survival of organic materials," the researchers wrote.

Although the mystery of the Princess of Bagicz's date of death has been solved, there is still more to learn about her and her culture.

"The woman did not exhibit any paleopathologies that could indicate the cause of death," Chmiel-Chrzanowska told Live Science in an email, but she did have osteoarthritis, which may have been from work-related overuse, given her young age of 25 to 35 when she died. Her osteoarthritis also suggests that the woman was a typical representative of the Wielbark culture rather than a princess, Chmiel-Chrzanowska wrote in a previous study.

"Next week, I am going to Warsaw for DNA testing" to learn more about the woman, Chmiel-Chrzanowska said. DNA analysis was previously attempted on the skeleton, but it was not successful. "We will attempt to drill into the skull in such a way as to obtain material from the temporal [skull] bone, without the need to damage it," she added.

Chmiel-Chrzanowska, M., R. Fetner, & M. Krąpiec. (2026). Unrevealing the date of a Roman Iron Age period burial in log coffin from Bagicz: A multidisciplinary approach.” Archaeometry. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.70113

Roman emperor quiz: Test your knowledge on the rulers of the ancient empire

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus