A fossilized foot found 15 years ago belonged to enigmatic human relative that lived alongside Lucy, scientists say

Freshly unearthed jaw bones and teeth that were found close to a previously discovered foot suggest human relatives tried several ways of walking before honing in on one strategy.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A mysterious fossilized foot found years ago in Ethiopia belongs to a controversial and enigmatic human relative that lived at the same time as our ancestor "Lucy," a new study finds.

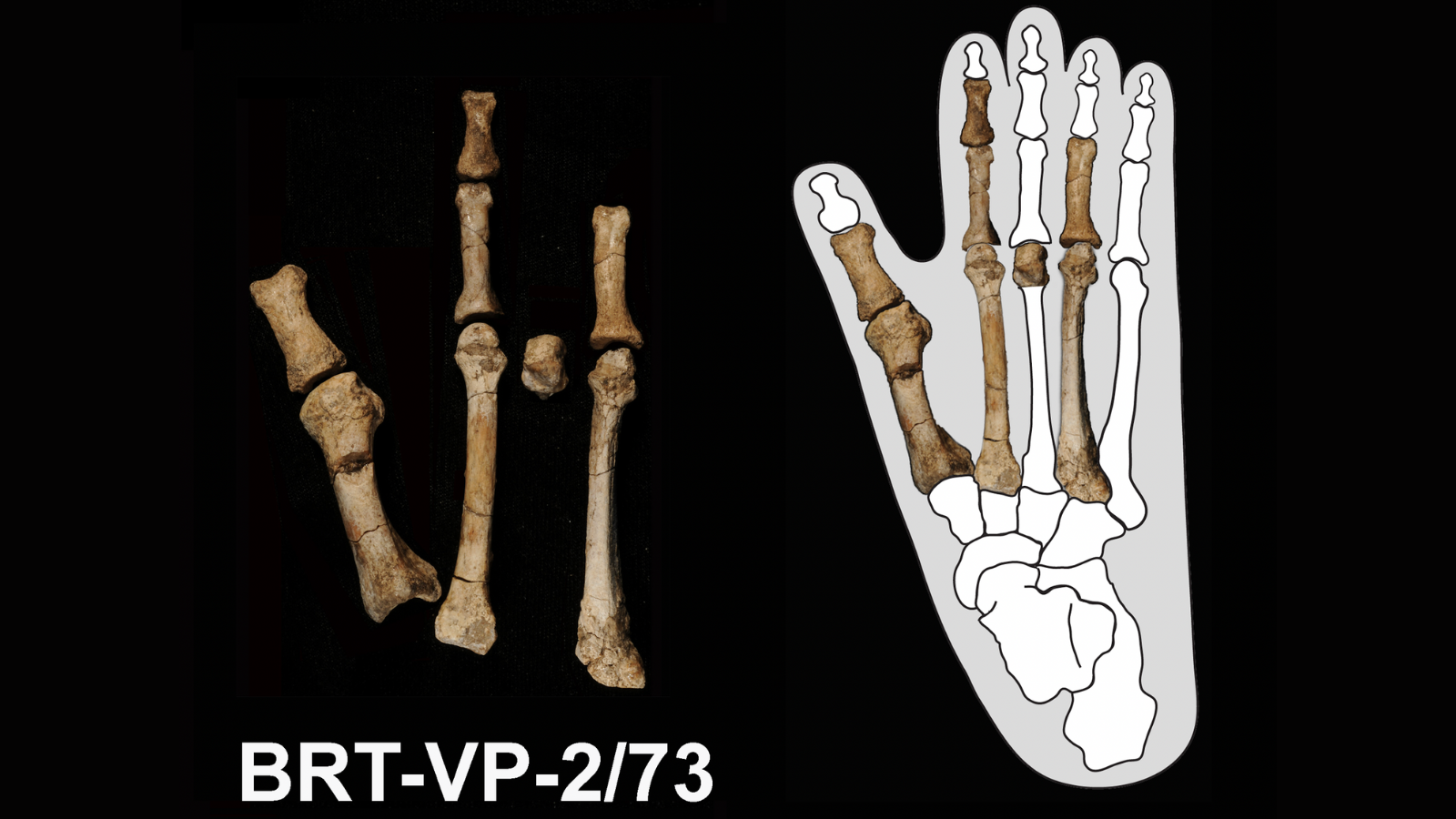

This discovery was years in the making. In 2009, scientists found the 3.4 million-year-old fossil foot that has toes designed for life in the trees. Now, newly discovered fossilized teeth and jaw bones found in the vicinity of the so-called "Burtele foot" suggest that members of Lucy's species, Australopithecus afarensis, lived side by side with another now-extinct human relative, Australopithecus deyiremeda, who lived from around 3.5 million to 3.3 million years ago.

The research, published Wednesday (Nov. 26) in the journal Nature, suggests Au. deyiremeda had an odd blend of features shared with members of Lucy's species, such as smaller canine teeth, as well as primitive characteristics seen in more ancient and ape-like hominins, such as opposable big toes that supported tree climbing.

But, like Lucy, Au. deyiremeda walked on two legs when on the ground, showing that different hominins living at the same time moved very differently from one another.

"What we are learning now is that, yes, bipedality was the key component of our evolutionary history, but there were so many ways to walk on two legs while on the ground," study first author Yohannes Haile-Selassie, a paleoanthropologist and director of Arizona State University's Institute of Human Origins, told Live Science.

He said that there were "a lot of experiments in bipedality," with different elements of the foot, pelvis and leg bones evolving at different rates and at different times.

A mystery was afoot

Before the discovery of the Burtele foot, hominins were believed to be fully bipedal by the time of Lucy, as she had a big toe that aligned with the other four digits. But the Burtele foot, which belonged to an adult, has long curved toes used for grasping tree branches.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers also previously found a jawbone with teeth at the same site in Ethiopia. However, they weren't sure if these remains belonged to the same species as the Burtele foot as they weren't sure if they came from the same time period.

In 2015, the species Au. deyiremeda was named based on this jawbone and others; however, this new species was controversial because the shape and size of the teeth are similar to Lucy's and an older hominin, Australopithecus anamensis.

Meanwhile, the species of the Burtele foot was unknown for years because bones from the head are needed for species designations, Haile-Selassie said. So he and his team went back to the Woranso-Mille site in the Afar region to look for more fossil remains.

The researchers found 13 new tooth and jaw fossil fragments of the same age close to where the Burtele foot was discovered. When compared with dental remains from other hominin species, these were "confidently" assigned to Au. deyiremeda, the researchers wrote in the new study. Based on their similar age and location, the team believe the teeth and foot belonged to members of the same species.

A chemical analysis of the tooth enamel revealed that, while both Lucy's species and Au. deyiremeda called Woranso-Mille home, they didn't need to fight for resources. Au. deyiremeda lived in a wooded environment and mainly ate from trees and shrubs, whereas Au. afarensis had a broad diet and lived in more open habitats.

"I think dietary differences and locomotion adaptation differences would be the best way to coexist," Haile-Selassie said. "Is that a surprise? Maybe not, because we know that modern primates today — closely related primates — they live together in the same area."

Controversial coexistence

The reaction to the Burtele foot belonging to Au. deyiremeda has been mixed.

Zeray Alemseged, a paleoanthropologist and professor of organismal biology and anatomy at the University of Chicago who was not involved in the new study, is not convinced that the foot and dental remains belong to the same species. He noted that the association is based on circumstantial evidence, namely them being close together in time and space.

Alemseged told Live Science that, if Au. deyiremeda is a separate species, to him it is unclear whether it belongs in the genus Australopithecus or if it's a late surviving species from the more ancient genus Ardipithecus, which is currently known to have lived until around 4.4 million years ago.

However, other experts agree that Lucy and her kind shared the landscape with this other Australopithecus species. Jeremy DeSilva, a biological anthropologist at Dartmouth College who was not involved in the research, said that Au. deyiremeda "is distinct anatomically, but to me what's much more valuable is how distinct it is behaviorally," such as being more selective in what it ate and spending more time in the trees.

In fact, DeSilva is now a convert, and thinks that A. deyiremeda is a separate species, and that the foot belongs to it. "Australopithecus deyiremeda always had a question mark next to it for me" since it was first proposed as a species, he told Live Science. "It doesn't anymore. That question mark's gone."

"To me, this paper is a 'welcome to the family tree' to Australopithecus deyiremeda," DeSilva added. "Now we've got our hands full trying to figure out, okay, where does this thing fit in?"

Human evolution quiz: What do you know about Homo sapiens?

Sophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers' 2025 "Newcomer of the Year" award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus