'Mitochondrial transfer' into nerves could relieve chronic pain, early study hints

A new study reveals that nerve cells receive periodic infusions of mitochondria from neighboring cells — and this may point to a new way of treating nerve pain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Supplying nerves with a fresh supply of mitochondria could curb chronic nerve pain, a new study hints.

The research, conducted with mouse cells, live mice, and human tissues, reveals a previously unsung role of mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells. It shows that support cells within the nervous system can ship mitochondria to the nerves that respond to pressure, temperature and pain. But problems with that shipping process can deplete the nerves' energy reserves, causing them to malfunction.

Whereas nerves would normally send a signal to the brain in response to some stimulus, dysfunctional nerves "fire sometimes spontaneously, even without stimulation," said senior study author Ru-Rong Ji, director of the Duke University School of Medicine's Center for Translational Pain Medicine and a professor of anesthesiology and neurobiology.

Article continues below"That will drive chronic pain and also will lead to neurodegeneration," Ji told Live Science, "because if you fire like crazy, eventually, that neuron probably will degenerate."

The new study, published Wednesday (Jan. 7) in the journal Nature, points to potential new ways of heading off that neuronal breakdown — and one strategy could involve transferring mitochondria directly into nerves.

Fresh mitochondria reduce pain

The research zoomed in on satellite glial cells, unique cells that physically wrap themselves around the "roots" of nerve cells located near the spinal cord. The bodies of these nerve cells cluster together near the spine, and from each cluster, bundles of long fibers extend to different parts of the body, from head to toe. The longest of these fiber bundles belong to the sciatic nerve, which measures just over 3 feet (1 meter) long.

The sheer length of the fibers poses a "real challenge," because for a nerve to function properly, mitochondria made in the nerve's root must travel down to the end of each fiber, and that in itself requires energy to do, Ji said. That raises a question of how nerves maintain this power-hungry supply chain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists once thought that cells had to make all of their own mitochondria, but in recent years, they have uncovered evidence that cells swap mitochondria. This can occur between cells of the same type or between cells of different types, such as between a stem cell and an immune cell, for example. To facilitate the swap, cells construct tiny structures called tunneling nanotubes for the mitochondria to travel through, like spitballs sliding from one end of a straw to another.

Ji and his team wondered whether satellite glial cells might be able to send mitochondria to the nerve cells they encircle — and it turns out that they can.

"We demonstrate that these cells actually extend these tunneling nanotubes to deliver in the mitochondria. This [finding] is unique in this study," Ji said.

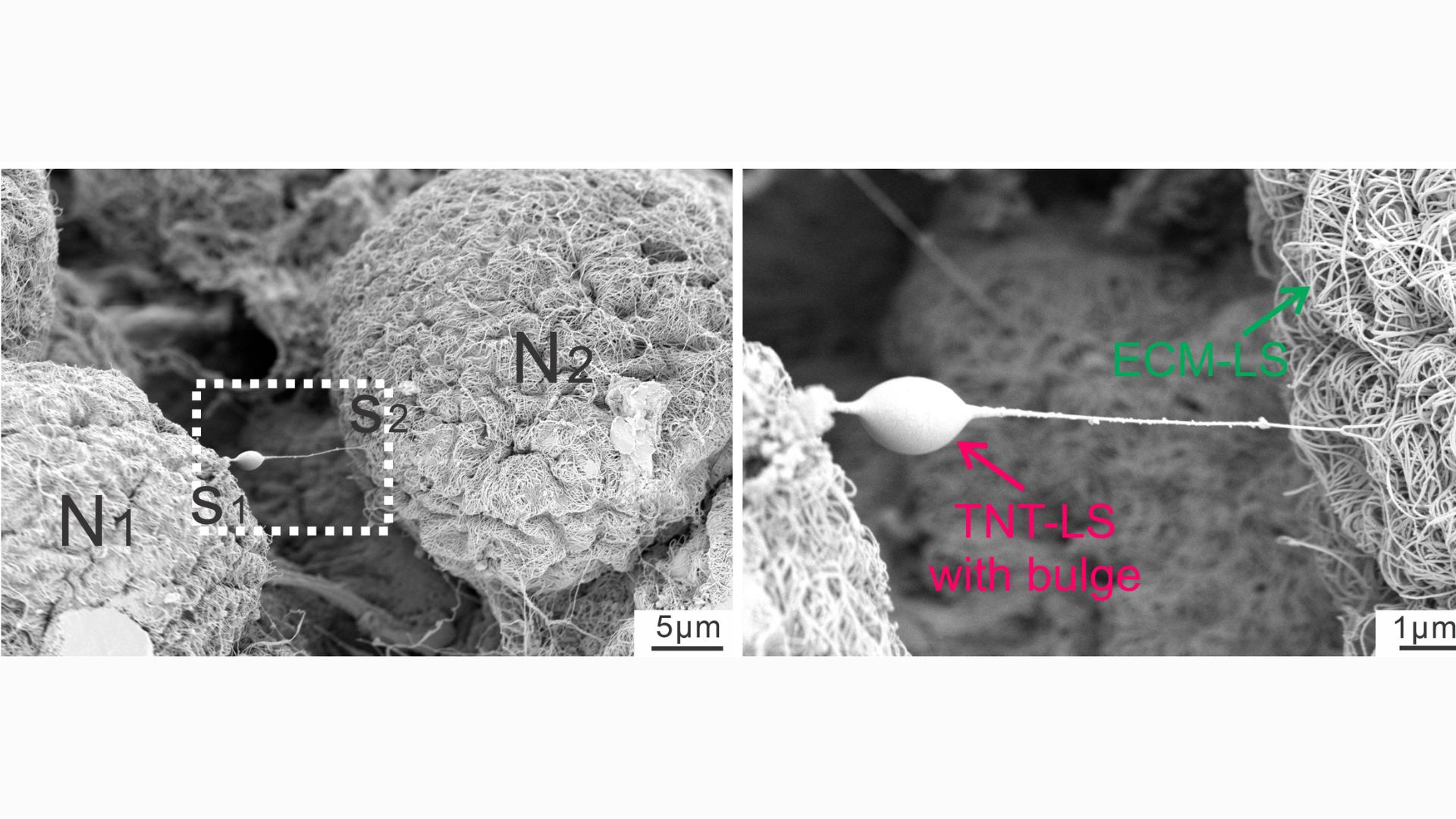

This close-up snapshot shows a nanotube extending from a neuron. The bulge in the tube indicates that something is being transported down its length.

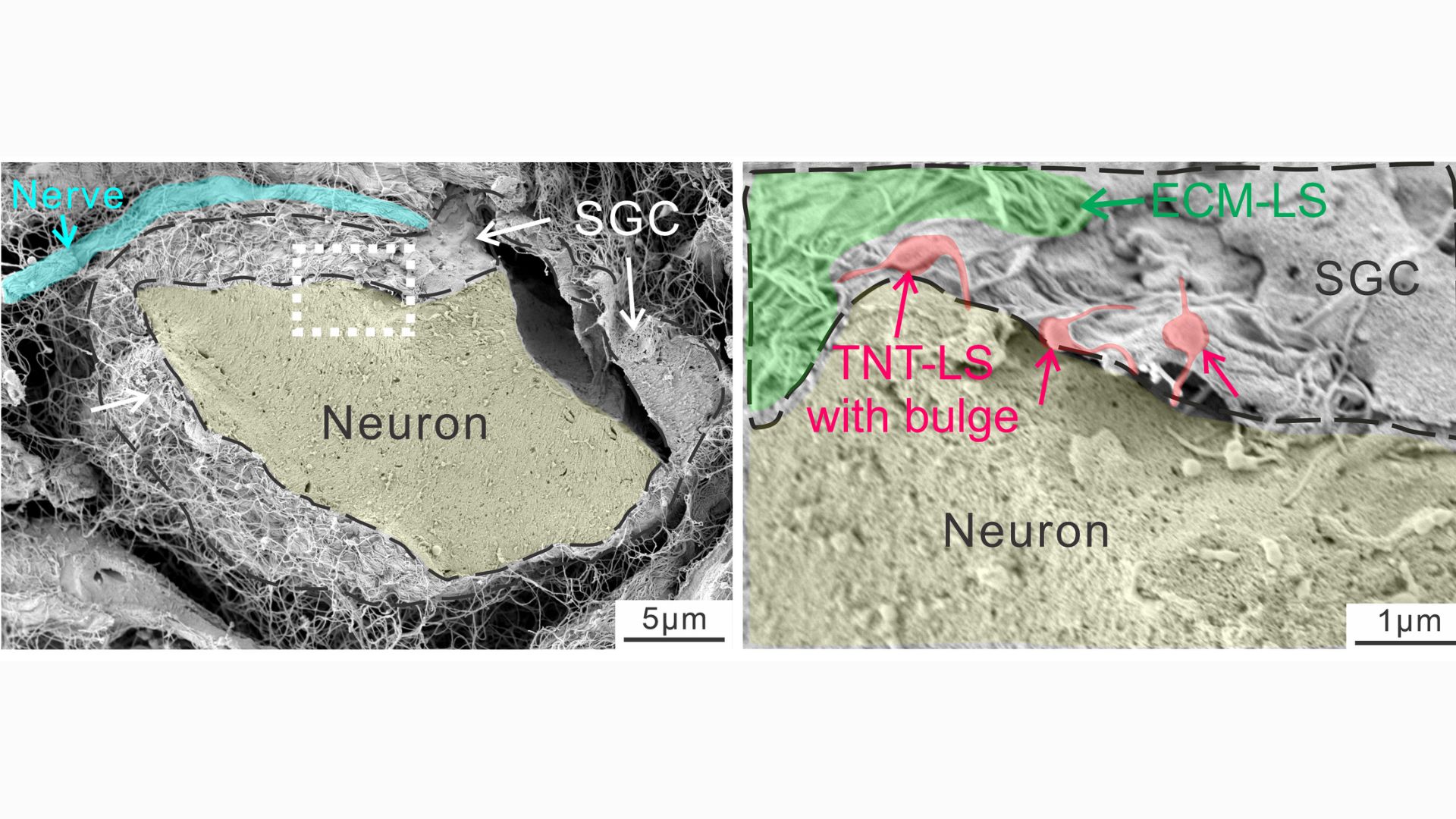

This diagram shows nanotubes linking glia to neurons, with bulges in the tubes indicating things being transported from the former cells to the latter. Later analyses revealed these transports to be mitochondria.

In a series of experiments with mouse cells and human tissues, the researchers took snapshots of the tiny tubes that formed between glia and nerve cells, noting distinct "bulges" that appeared in the tubes as materials traveled through them. By tacking a fluorescent tag onto mitochondria, they were able to track instances in which powerhouses from glial cells made their way into the nerves.

The nanotubes were transient structures that broke down soon after a given transfer was complete. Experiments showed that a protein called MYO10 was critical to the tubes' construction, helping to extend them out from the glia. But additionally, the mitochondria could sometimes be transferred without the tubes, either inside tiny bubbles released by glia or through special channels that formed between the membranes of the donor and recipient cells.

In healthy lab mice, the researchers found that disrupting these different modes of mitochondria shipment made the mice more sensitive to pain. That's because it spurred damage in the nerves and caused them to fire abnormally.

They also looked at mice with various types of nerve damage, such as from exposure to chemotherapy drugs or from diabetes. These nerve-damaging conditions also disrupted the mitochondrial exchange from glia to some degree, and this contributed to nerve pain in the lab mice. Transferring healthy glia into the mice alleviated the pain, though, by providing them with a fresh source of healthy mitochondria.

A new view on glia

Notably, nerve damage from diabetes and chemotherapy tends to hit the smallest nerve fibers the hardest, whereas medium and large fibers show more resilience. In the team's experiments, they found that the larger nerve fibers appeared to receive a higher volume of mitochondria from glia, while small fibers got fewer by comparison. In short, it seems that glia have a "preference" toward lending their mitochondria to larger fibers, the study authors wrote.

"That is still a puzzle. We don't know why that's the case," Ji said. But nonetheless, it might begin to explain why small fibers are more vulnerable to damage in these conditions, triggering symptoms of numbness, painful tingling or burning in the feet and hands.

More studies are needed to fully understand how mitochondria are shuttled from glia to nerve cells in health and disease. This fundamental research could pave the way to future treatments for nerve pain, the team thinks. In theory, treatments could be aimed at boosting the activity of satellite glial cells, so they produce and transfer more mitochondria.

Or alternatively, mitochondria could be harvested from cells grown in the lab, purified, and then injected straight into nerves as a treatment, he added.

Historically, glia were solely thought of as the glue of the nervous system, providing structural support to neurons by binding them together. But scientists have since uncovered that glia are involved in processes once thought to be handled only by neurons, like memory. And the new study suggests glia may actually be physically plugged into neuronal networks, Ji said.

"If they can transport mitochondria, such a very large organelle, in that tube, then you can transport many other things, right?" he suggested. "That means the neurons and the glial cells, they are much more connected than we thought."

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus