60,000-year-old poison arrows from South Africa are the oldest poison weapons ever discovered

Five quartz arrowheads found in a South African cave were laced with a slow-acting tumbleweed poison that would have tired prey during long hunts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

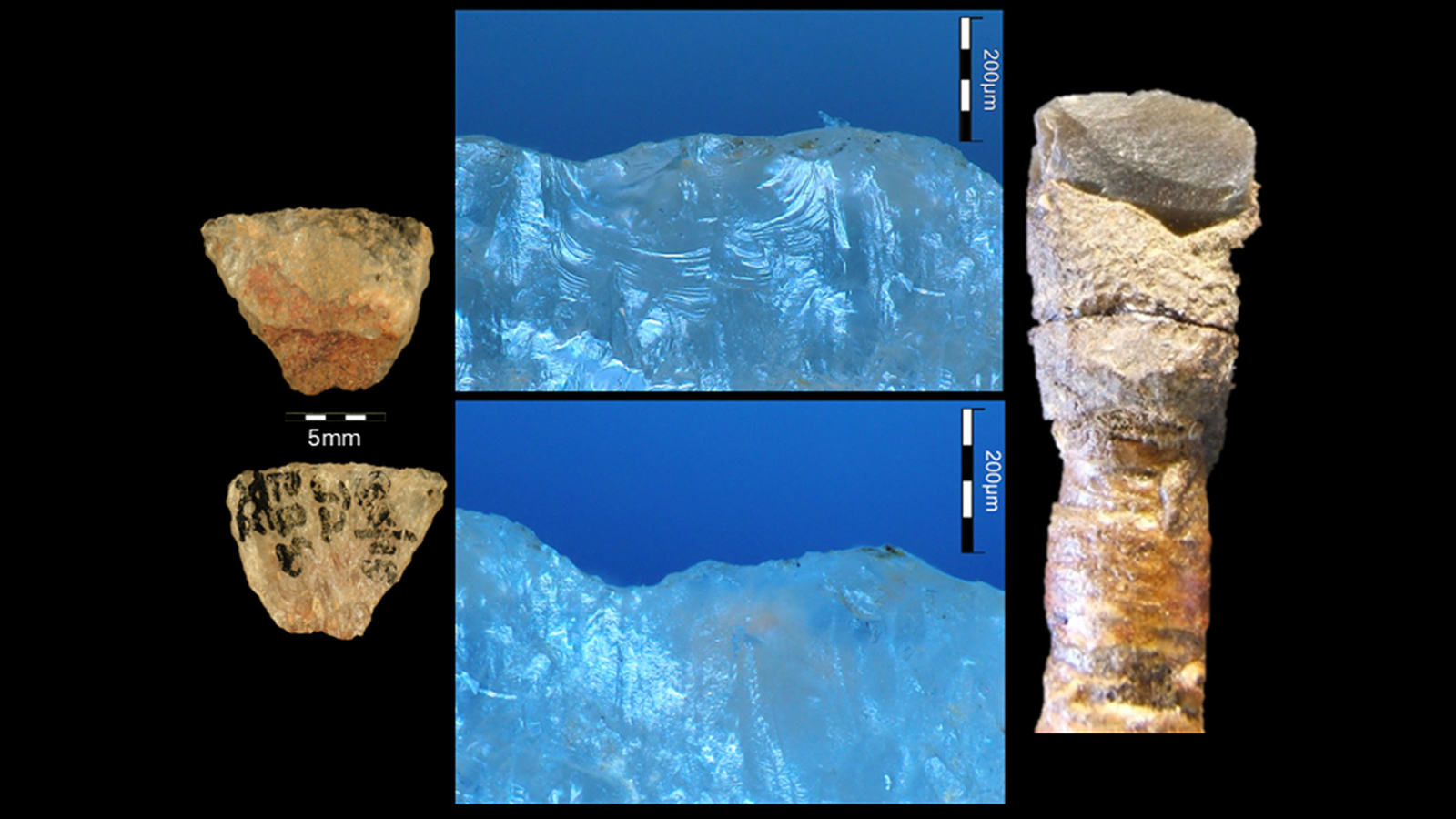

A handful of 60,000-year-old arrow tips unearthed in a South African rock shelter are the oldest evidence of poison weapons in the world, a new study finds.

The discovery pushes back the confirmed use of poison weapons by hunter-gatherers by over 50,000 years.

In the new study, scientists chemically analyzed 10 arrow tips that had been found decades ago at Umhlatuzana rock shelter. They found that five still contained traces of slow-acting poisons. These substances, likely derived from a species of tumbleweed, would have weakened targeted prey and substantially cut down the time and energy required for persistence hunts, the authors wrote in the study published Wednesday (Jan. 7) in the journal Science Advances.

Article continues belowThe finding shows that prehistoric hunter-gatherers understood the pharmacological effects of these plants, the researchers said.

"Humans have long relied on plants for food and manufacturing tools, but this finding demonstrates the deliberate exploitation of plant biochemical properties," study lead author Sven Isaksson, a professor of laboratory archaeology at Stockholm University, told Live Science.

What's more, the poisoned arrow tips reveal that these prehistoric hunters could think in complex ways. The poison takes time to have an effect, so the hunters had to understand cause and effect and plan ahead for their hunts, Isaksson said.

Previously, the oldest unequivocal evidence for poison-weapon use was 7,000-year-old arrow poison tucked into the thigh bone of a hoofed mammal found in Kruger Cave in South Africa. Although there have been older findings — such as indirect evidence of a 24,000-year-old wooden "poison applicator" from Border Cave, also in South Africa — they are debated.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Poisoned weapons

Poisons degrade over time, but traces of these chemicals can survive in certain conditions.

The Umhlatuzana rock shelter, excavated in 1985, is one prime location for such conditions. Archaeologists had previously unearthed 649 crafted quartz fragments from the Howiesons Poort period, a distinct South African technological culture dating from 65,000 to 60,000 years ago. But no one had closely inspected the surfaces of these remnants, beyond looking for glues used to attach the arrow tips to the arrows' shafts.

For the new study, Isaksson and his team took a closer look at 10 of the 216 available arrowheads from an excavation layer dated to 60,000 years ago; these 10 were selected because they still had microscopic residue that could be analyzed.

The researchers found traces of the plant-derived toxin buphandrine in the residue from five of the arrowheads, with one also containing the toxin epibuphanisine. All five arrowheads were probably originally laced with both toxins, but there were not enough remains to be detected using current technology, Isaksson said.

Both toxins are found in plants across southern Africa, but only the species Boophone disticha — known locally as "poison bulb" — is well known as arrow poison, making it the most likely source of the poison. In fact, the team also detected the two poisonous chemicals in four arrows from 18th-century South Africa. An analysis of the milky extract from modern B. disticha bulbs confirmed the presence of both toxins in the species. Although there is no evidence that B. disticha grew in the area 60,000 years ago, the plant is found less than 8 miles (12.5 kilometers) from the rock shelter today.

The discovery of these ancient poison arrows is "quite remarkable," Justin Bradfield, an associate professor of archaeology at the University of Johannesburg who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

Importantly, the hunter-gatherers at Umhlatuzana seem to have used a single-component poison; more complex recipes, like the one found at Kruger Cave, were potentially invented much later, Bradfield said.

Archaeologists have long assumed that hunter-gatherers were aware of plant toxins and their uses. However, the new finding reveals that these toxins can survive for tens of thousands of years, and this opens the door for more research, Bradfield said.

Going forward, the team plans to look at younger deposits at the rock shelter to determine whether poison-arrow use was a continuous practice or if it died out before being rediscovered.

Stone Age quiz: What do you know about the Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic?

Sophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers' 2025 "Newcomer of the Year" award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus