In Photos: Oldest Homo Sapiens Fossils Ever Found

Shelter in a cave

Researchers working at an archaeological site called Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, in northwestern Africa, have made a huge find: the remains of the oldest-known Home sapiens ever found on Earth. The remains, which include a partial skull and jawbone, belonged to five individuals, including a teenager and a younger child. All of these remains date back about 300,000 years, which pushes the origin of our species back 100,000 years, the researchers said. Their work is published in two papers in the June 8, 2017, issue of the journal Nature.

Here, a view of the site showing the remaining deposits and people excavating them (center). Some 300,000 years ago, this site, which would have been a cave, was occupied by early hominins.

[Read the full story on the discovery]

A dark notch

The excavation area is visible as a dark notch a little more than halfway down the ridge line sloping to the left in this image of the archaeological site of Jebel Irhoud in Morocco.

Seeing our roots

Dr. Jean-Jacques Hublin is shown here when he first saw the new finds at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco. He is pointing to the crushed human skull of one of the individuals found there. The eye orbits are visible just beyond his fingertip.

Crushed skull

Two of the new Jebel Irhoud fossils, shown as they were discovered during excavation. The crushed top of a human skull (from the individual dubbed Irhoud 10) can be seen in the center of the image (in a yellow-brown hue). Just above that skull, resting against the back wall, is a partial femur from another individual (dubbed Irhoud 13). What you can't see in this image is the mandible of individual Irhoud 11, located between the femur and the skull behind the pointed rock.

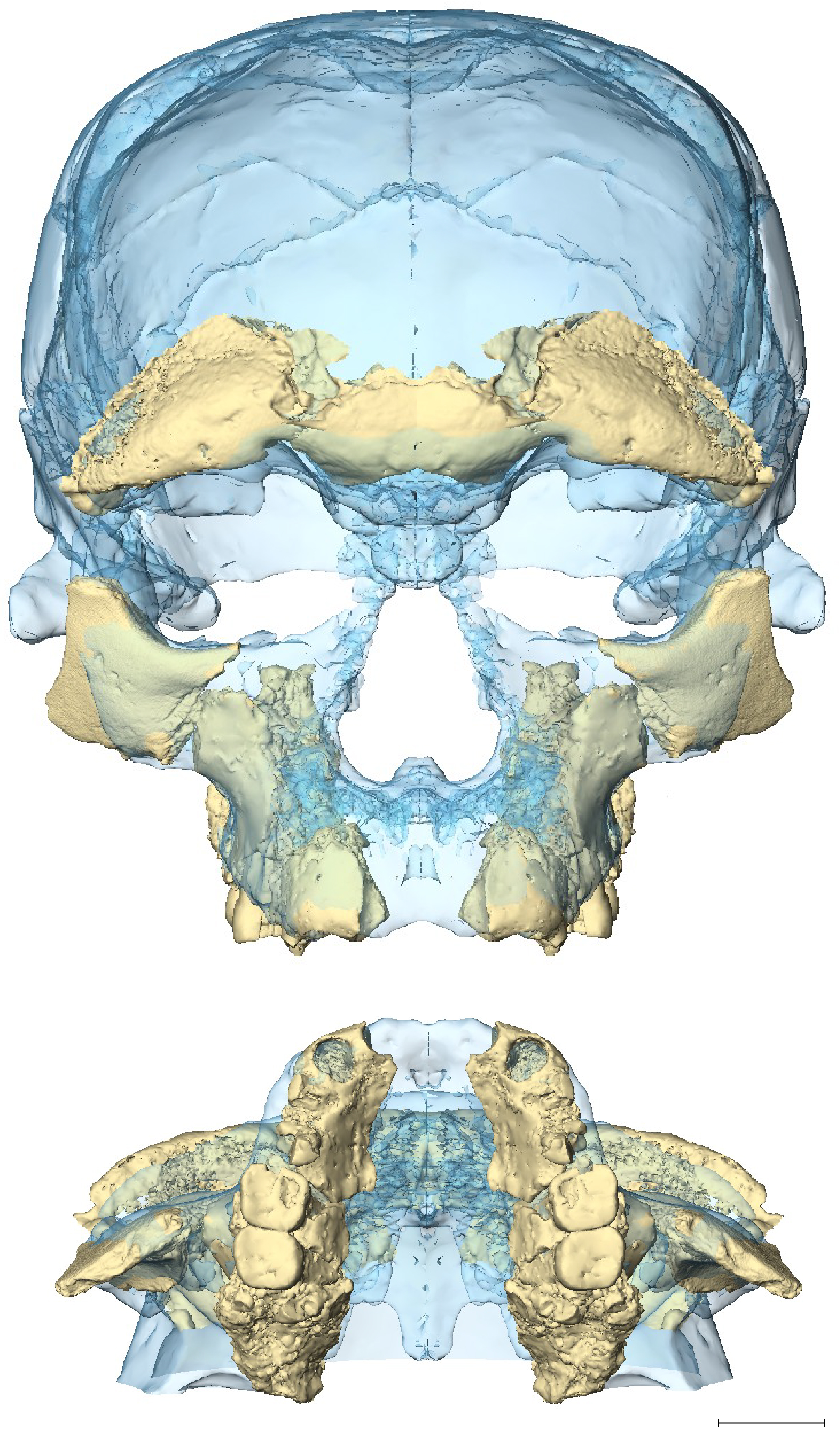

Modern faces

The researchers scanned several of the fossils with micro-computed tomography (micro-CT). They used the resulting images to create a composite reconstruction of the skull and other fossils found at the Morocco site. These early Homo sapiens, the researchers found, looked a lot like humans living today; they had modern-looking faces.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Not as brainy

Two views of a composite reconstruction of the earliest known Homo sapiens fossils from Jebel Irhoud site. Though their faces may have appeared modern, the archaic-looking braincase (blue) suggests that brain shape, and maybe even brain function, were different, the researcher said.

2 Views

These are two views of the face of one of the individuals, dubbed Irhoud 10, whose remains were found at the Morocco site. All the proposed reconstructions of the individual's face result in features that were in line with what would be found today, the researchers noted. The finding suggests that the modern structure of the face was already in place 300,000 years ago in the earliest Homo sapiens known to date.

Robust mandible

The mandible of another individual, called Irhoud 11, represents the first, almost complete adult mandible discovered at the site of Jebel Irhoud in Morocco. The shape of the bone and the dentition had both archaic and more evolved features, the researchers noted.

Virtual mandible

This virtual reconstruction of the mandible of Irhoud 11 mandible allowed the researchers to compare it with the mandibles of archaic hominins, such as Neanderthals, as well as early forms of anatomically modern humans.

Making points

Researchers also found tools dating to the Middle Stone Age at the Morocco site. The tools included stone points as well as stone core flakes prepared using the so-called Levallois method developed by the precursors to modern humans.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus