These 125 million-year-old fossils may hold dinosaur DNA

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The remnants of DNA may lurk in 125 million-year-old dinosaur fossils found in China. If the microscopic structures are indeed DNA, they would be the oldest recorded preservation of chromosome material in a vertebrate fossil.

DNA is coiled inside chromosomes within a cell's nucleus. Researchers have reported possible cell nucleus structures in fossils of plants and algae dating back millions of years. Scientists have even suggested that a set of microfossils from 540 million years ago might hold preserved nuclei.

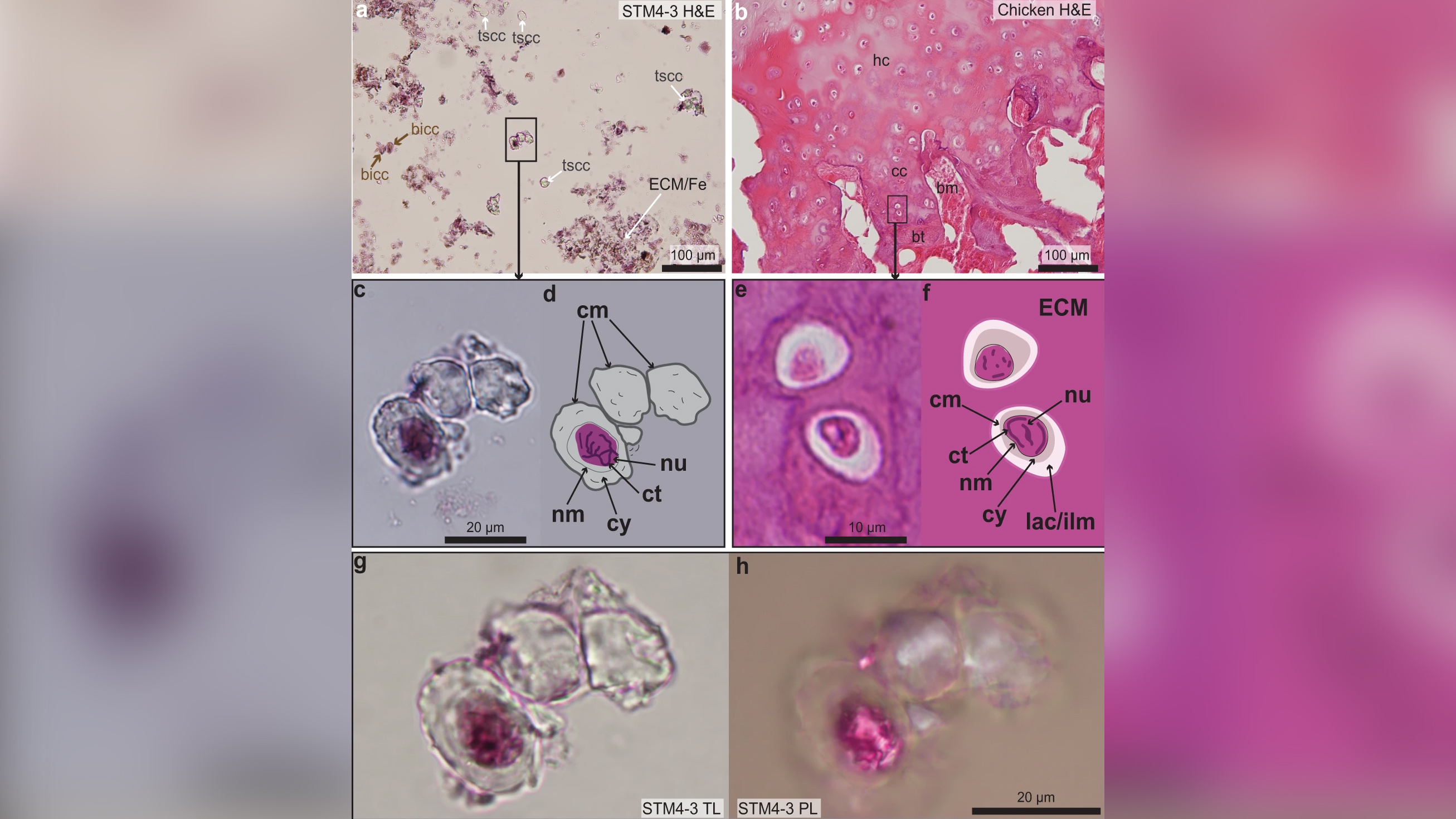

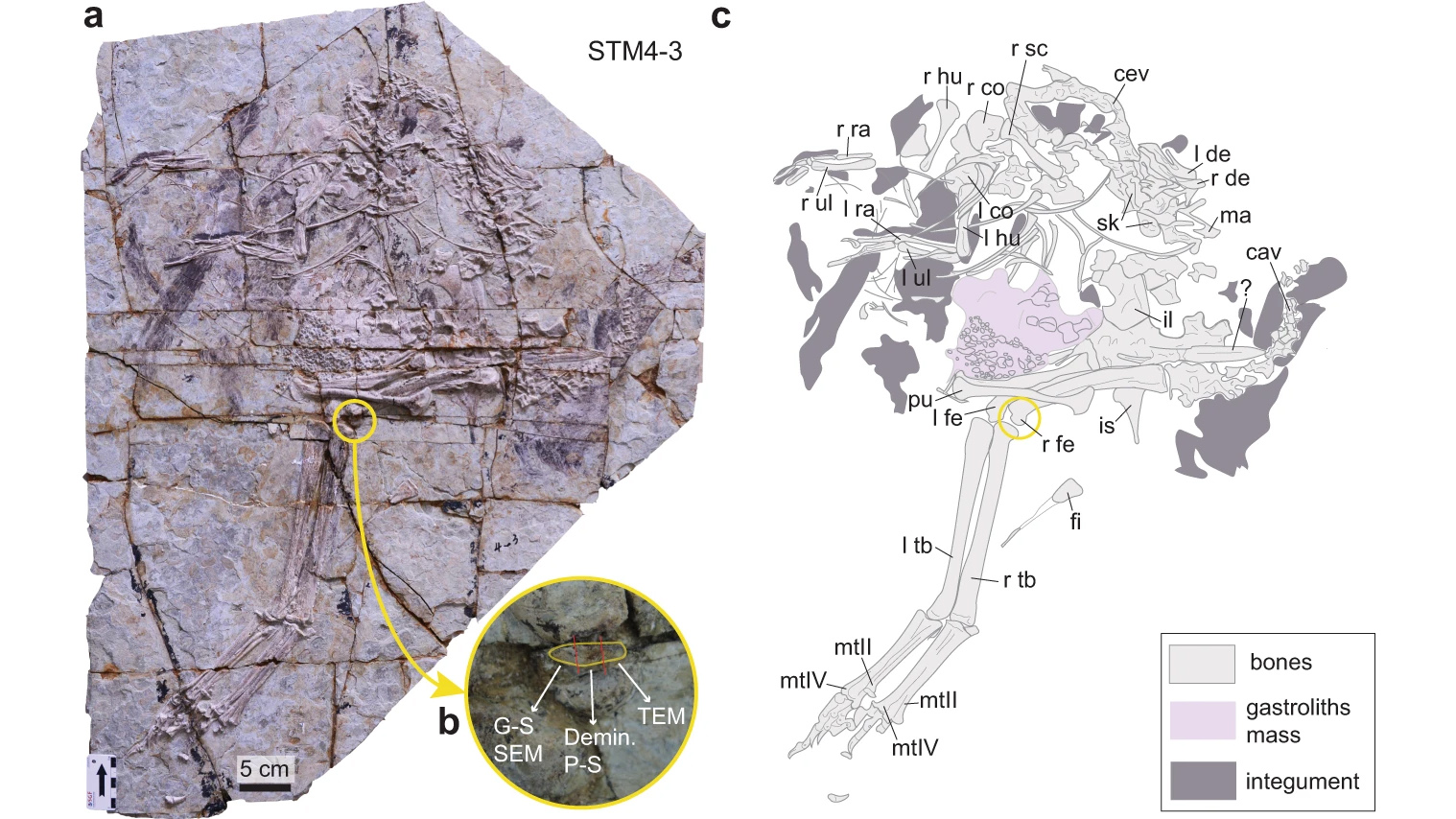

These claims are often controversial, because it can be hard to distinguish a fossilized nucleus from a random blob of mineralization created during the fossilization process. In the new study, published Sept. 24 in the journal Communications Biology, researchers compared fossilized cartilage from the feathered, peacock-size dinosaur Caudipteryx with cells from modern chickens; they found structures in the fossils that looked much like chromatin, or threads of DNA and protein.

"The fact that they are seeing this is really interesting, and it suggests we need to do more research as to what happens to DNA and chromosomes after cell death," said Emily Carlisle, a doctoral student who studies microscopic fossils and their preservation at the University of Bristol in England but was not involved in the new research.

Dino DNA?

To answer the obvious burning question: No, we're nowhere close to resurrecting dinosaurs from their fossilized DNA.

"If there is any DNA or DNA-like molecule in there, it will be — as a scientific guess — very, very chemically modified and altered," Alida Bailleul, a paleobiologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences who led the new research, wrote in an email to Live Science.

Related: Is it possible to clone a dinosaur?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, Bailleul said, if paleontologists can identify chromosome material in fossils, they may someday be able to unravel snippets of a genetic sequence. This could reveal a little more about dinosaur physiology.

But first, researchers have to find out if the DNA is even there. Until recently, most paleontologists thought that rot and decay destroyed the contents of cells before fossilization could take hold. Any microscopic structures inside cells were considered collapsed cell contents, such as organelles and membranes, that had rotted before mineralization, Carlisle told Live Science. More recently, though, paleontologists have found legitimate cell structures in a few fossils. For example, 190 million-year-old fern cells described in 2014 in the journal Science were buried in volcanic ash and fossilized so quickly that some were frozen in the process of cell division. Unmistakable chromosomes are visible in some of these cells.

In 2020, Bailleul and her colleagues reported the possible preservation of DNA in the skull of an infant Hypacrosaurus, a kind of duck-billed dinosaur that lived 75 million years ago, found in Montana. The possible DNA was found in cartilage, the connective tissue that makes up the joints.

"We were specifically interested in the cartilage because it's a very good tissue for cellular preservation, perhaps even more so than bone," Bailleul said.

Hidden in stone

For the new study, the researchers turned to a well-preserved specimen of Caudipteryx held by the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature in China. Originally discovered in the northeastern province of Liaoning, the fossil has ample preserved cartilage, which the researchers stained with the same dyes used to image DNA in modern tissue. These dyes bind to DNA and turn it a specific color, depending on the dye, allowing the DNA to stand out against the rest of the nucleus. By examining the stained, fossilized cartilage with several microscopy methods, Bailleul and her team showed that the cartilage cells contain structures that look just like nuclei with a scramble of chromatin inside.

Related: Photos: Fossilized dinosaur embryo discovered

The stained dinosaur nuclei's resemblance to modern cells doesn't prove there is DNA inside them, though, Bailleul cautioned. "What it means is that there are definitely parts of original organic molecules, perhaps some original DNA in there, but we don't know that yet for sure," she said. "We just need to go figure out exactly what these organic molecules are."

The imaging definitely seems to show nuclei, Carlisle said, but it's harder to identify fossilized chromosomes, because no one really knows what happens to chromosomes as they decay. It's possible that the contents of the nucleus might just collapse into structures that look like chromosomes but are really just a jumble of meaningless mineralized junk; it's also possible that the fossilization process preserves some of the original molecular structure. (One 2012 study suggests that DNA in bone will completely break down in about 7 million years, but the timing may depend heavily on environmental factors.)

"It would be really interesting to do more experiments into that, looking at what happens inside the nuclei instead of just what happens to it from the surface," Carlisle said.

Bailleul and her colleagues hope to collect more chemical data to nail down the identity of the mysterious structures.

"I hope we can reconstruct a sequence, someday, somehow," she said. "Let's see: I could be wrong, but I could also be right."

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus