This new DNA storage system can fit 10 billion songs in a liter of liquid — but challenges remain for the unusual storage format

The new storage system could hold family photos, cultural artifacts and the master versions of digital artworks, movies, manuscripts and music for thousands of years, scientists say.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The U.S. biotech company Atlas Data Storage has launched a synthetic DNA storage system capable of holding 1,000 times more data than traditional magnetic tape.

The product, called Atlas Eon 100, claims it will store humanity’s "irreplaceable archives" for thousands of years. These include family photos, scientific data, corporate records, cultural artifacts and the master versions of digital artworks, movies, manuscripts and music.

"This is the culmination of more than ten years of product development and innovation across multiple disciplines," Bill Banyai, Founder of Atlas Data Storage, said in a statement. “We intend to offer new solutions for long-term archiving, data preservation for AI models, and the safeguarding of heritage and high-value content."

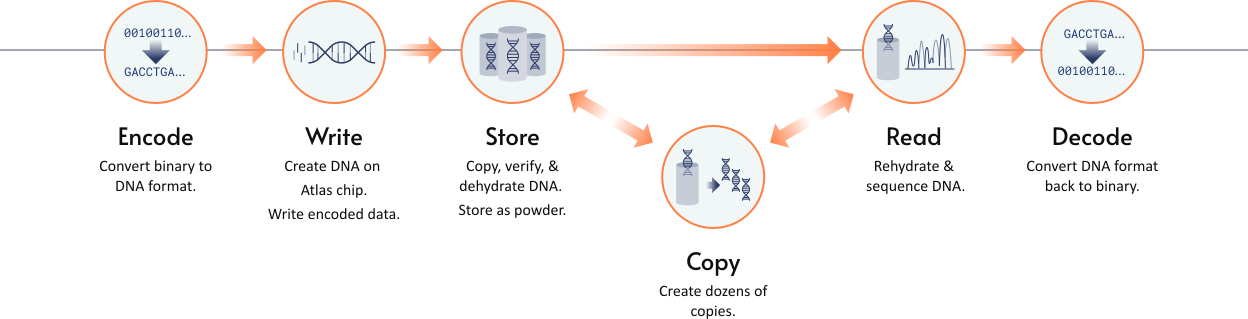

Article continues belowFundamentally, all digital data is just a series of 1s and 0s in a defined sequence. DNA is similar in that it is made up of defined sequences of the chemical bases adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T).

DNA data storage works by mapping the binary code to these bases; for example, an encoding scheme might assign A as 00, C as 01, G as 10, and T as 11. Artificial DNA can then be synthesized with the bases arranged in the corresponding order.

For Atlas Eon 100, the DNA is then dehydrated and stored as a powder in 0.7-inch-tall (1.8 cm) ruggedized steel capsules. It is rehydrated only when it needs to be sequenced and its bases translated back to binary.

More useful than magnetic tape

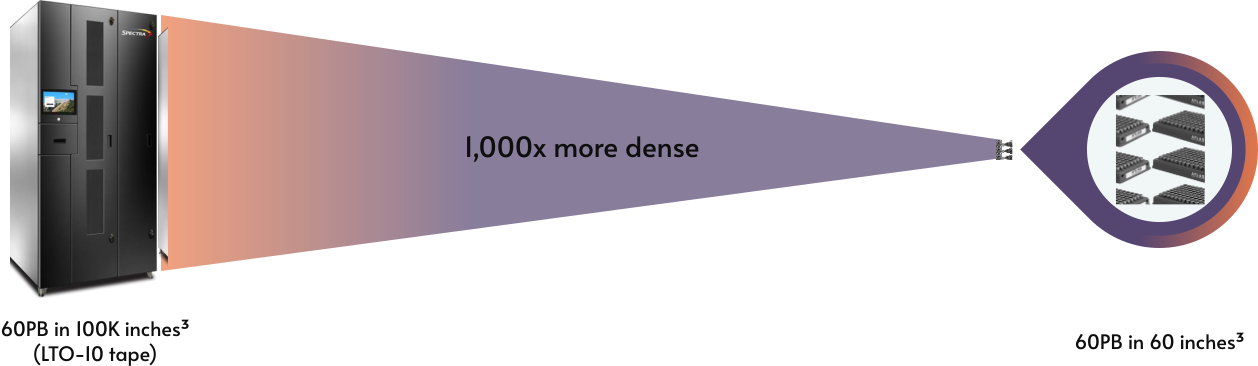

Just one quart (one liter) of the DNA solution can hold 60 petabytes of data — the equivalent of 10 billion songs or 12 million HD movies. This makes Atlas Eon 100, which was announced on Dec. 2, 1,000 times more storage-dense than magnetic tape.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For context, about 15,500 miles (25,000 km) of 0.5-inch-wide (12.7 mm) LTO-10 tape, a standard high-capacity storage medium, would be needed to hold that same amount of data.

This storage density will make transporting large quantities of data easier than it would be with typical hard drives or tape reels. DNA is also known to keep its form for centuries, making it a remarkably stable medium for preserving data over very long periods.

Atlas Data Storage says its product is stable in an office environment with 99.99999999999% reliability, but the capsules can also endure temperatures as high as 104°F (40°C). Magnetic tape, on the other hand, decays in about a decade even with temperature and humidity controls.

Optical media, such as CDs and DVDs, typically degrade within 30 years, while hard drives last about 6 or 7 years before showing signs of deterioration. In less than 3 hours at 158°F (70 °C), a flash memory cell can ‘age’ as much as it normally would in a month.

Atlas also argues that its DNA storage service offers an easier way to make backups of its customers’ data than other media do. Indeed, once one strand is encoded, enzymes can be used to make more than a billion copies in just a few hours.

A solution for a data-hungry society?

According to Atlas, society generates 280 PB of data every minute. It presents its DNA data storage as a potential solution to the proliferation of digital data, which has been exacerbated massively by the generative artificial intelligence (AI) boom.

However, the biotech faces a key scaling challenge: synthesizing encoded artificial DNA is still quite a long process compared with, say, saving a photo on an existing hard drive. Twist Bioscience, Atlas’s former parent company from which it inherited its DNA synthesis process, currently has a lead time of between 2 and 8 business days on gene and oligo (short and long DNA strands) orders.

Sequencing is notoriously expensive, too; it costs about $30 USD to read one gigabase of DNA, the equivalent of about 250 GB of data. It also takes a long time, with another recent DNA storage resolution reporting that it takes 25 minutes to recover a single file. Nevertheless, Atlas Data Storage claims that modern DNA sequencers are “improving throughput and cutting costs 1,000× faster than Moore’s Law.”

That said, due to the time required to synthesize and sequence DNA, the DNA Data Storage Alliance noted in 2025 that they do not expect DNA to be used for archival data storage at scale for another three to five years.

Professor Thomas Heinis, a computer science professor at Imperial College London who researches DNA-based data storage, is sceptical about the lack of concrete data that Atlas has published about the performance of Atlas Eon 100. He pointed to the fact that Catalog DNA, which made similar promises about its Shannon storage solution, went bust a few months ago.

"I have no doubt that they have built an impressive device, but it’s difficult to appreciate without concrete information," he told Live Science, adding that the major challenge to commercialising DNA storage is synthesis, not sequencing.

"It sounds banal, but if the write/synthesis cost is not competitive, then there is no point in reading/sequencing cost efficiently. You cannot read (cheaply) what you cannot afford to write. Currently, synthesis is orders of magnitude too expensive while sequencing is closer to tape but still more expensive. Despite being a firm believer in DNA storage, a lot of technological progress is needed and I have not seen anyone with an economically viable solution yet."

Fiona Jackson is a freelance writer and editor primarily covering science and technology. She has worked as a reporter on the science desk at MailOnline, and also covered enterprise tech news for TechRepublic, eWEEK, and TechHQ.

Fiona cut her teeth writing human interest stories for global news outlets at the press agency SWNS. She has a Master's degree in Chemistry, an NCTJ Diploma and a cocker spaniel named Sully, who she lives with in Bristol, UK.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus