Nightmare Creature Had Egg-Shaped Eyes, Swiss Army Knife Head and a Butt Shield

The animal was no bigger than a human thumb, but it was a deadly predator.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A spiky, armor-plated "walking tank" with bulging eyes, a shield on its butt and a head like a Swiss army knife scuttled along the seafloor more than 500 million years ago, snapping up prey with a deadly pair of mouth pincers called chelicerae.

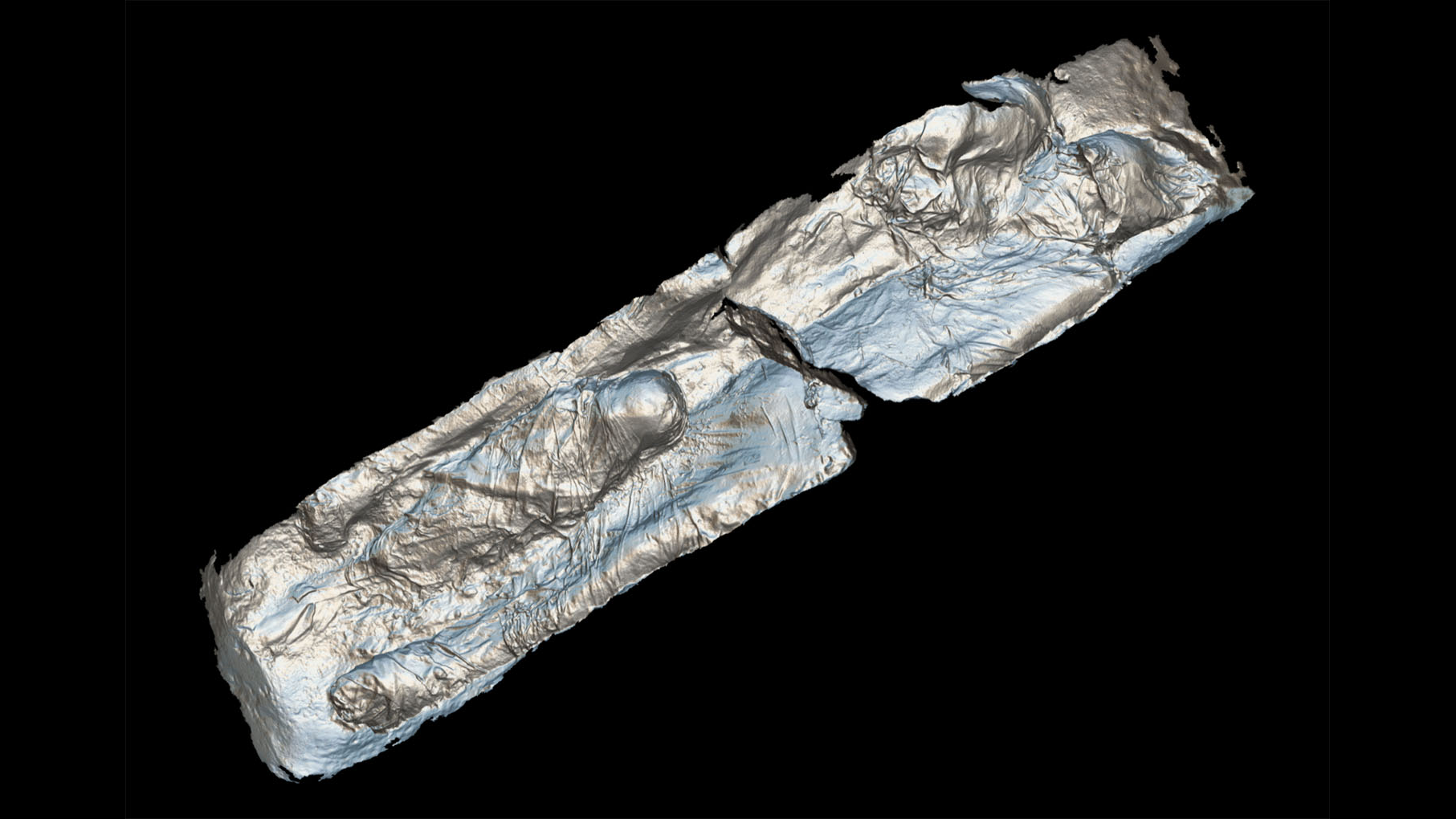

Researchers discovered astoundingly well-preserved fossils of these thumb-size predators in 2012, and a new study recently described the creatures, determined to be a previously unknown species now dubbed Mollisonia plenovenatrix. Scientists have found dozens of fossils of this species in recent years that include preserved soft tissue of the mouthparts, along with the animals' multiple legs and bulbous eyes.

The mouth pincers, in particular, caught scientists' attention. Chelicerae are found in a diverse group of animals called chelicerates; the group includes more than 115,000 species alive today, among them spiders, scorpions and horseshoe crabs. These fossils provided the oldest evidence to date of these mouth appendages. But these robust pincers may have originated in an unknown species that is even older, the study said.

Related: Image Gallery: Cambrian Creatures: Primitive Sea Life

M. plenovenatrix had a segmented body covered with protective plates. Broad, spine-studded shields covered the creature's rear and head, which was topped with bulbous eyes. The animal likely used its three pairs of legs to trot along the sea bottom, the study authors reported.

The newly described species had a wider, plumper body than other, similar Mollisonia creatures that scientists knew only from partial fossils of their shed exoskeletons. And its name — from "plena venatrix," which means "plump huntress" in Latin — reflects that, lead study author Cédric Aria, a postdoctoral fellow with the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, told Live Science in an email.

Not only were the chelicerae exquisitely preserved, but the creature also sported gill-like respiratory structures that were surprisingly similar to those in modern chelicerates. This find hinted that chelicerae likely first appeared in a species that predated M. plenovenatrix, the study said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The rocks have eyes

Researchers uncovered the first evidence of the Mollisonia genus more than 100 years ago, in Burgess Shale deposits in British Columbia. But those fossils were only empty carapaces that the growing arthropods had discarded, so a lot of questions remained about the animal's anatomy, said study co-author Jean-Bernard Caron, a curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

Then, in 2012, scientists hit the Mollisonia jackpot in another Burgess Shale location; called Marble Canyon, it sits about 25 miles (40 kilometers) from the site where the first fossil carapaces appeared. In fact, M. plenovenatrix was among the first fossils researchers found, and they spotted it because of its bulging, oversize eyes peering back at them from the rock, Caron told Live Science.

"With additional material, we realized there was more than just the eyes preserved — there were also limbs," Caron said.

Over the next six years, the researchers returned to the site and excavated 49 M. plenovenatrix specimens, most of which included preserved soft tissues. The fossils also presented the animals in different positions, providing highly detailed views of their bodies from multiple angles, Caron said.

The Mollisonia exoskeleton fossils found in the Burgess Shale dated to about 480 million years ago, while the Marble Canyon fossils date to more than 500 million years ago. "So, we are pushing back the origin of this group by 20 [million] to 25 million years," Caron said.

Mollisonia probably lived in or near a steeply sloping part of the seafloor that was home to diverse marine life, such as trilobites, bristle worms "and ice cream cone-like shelly animals called hyoliths; those might have in fact been on Mollisonia's menu, although we lack direct evidence from gut contents to be certain," Aria said in the email. In turn, arthropod predators such as Tokummia, an ancient relative of modern centipedes, may have used its giant mandibles to chomp on Mollisonia, Caron added.

Indeed, M. plenovenatrix wasn't the only underwater weirdo produced by the Cambrian period (541 million to 485 million years ago). Life on Earth erupted during the Cambrian, producing numerous oddball animals such as giant, bristle-mouthed shrimp; a toothy "penis worm"; an arthropod larva with a tail like a dagger; a "beautiful nightmare" crab with soccer ball eyes; and a creature that resembled the Millennium Falcon of "Star Wars."

When it comes to animal body plans, evolution during the Cambrian ably demonstrated that "reality often surpasses fiction" — particularly for Mollisonia, which possessed an arresting combination of "dread and beauty," Aria said.

"The past is full of complexity and surprises. Mollisonia adds an important piece to the puzzle of biodiversity," he said.

The findings were published today (Sept. 11) in the journal Nature.

- Photos: 'Naked' Ancient Worm Hunted with Spiny Arms

- Gallery: Amazing Cambrian Fossils from Canada's Marble Canyon

- These Bizarre Sea Monsters Once Ruled the Ocean

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus