The choice of sperm is 'entirely up to the egg' — so why does the myth of 'racing sperm' persist?

In her new book "The Stronger Sex," science journalist Starre Vartan dispels myths and misconceptions about the female body.

It's a commonly held belief: Sperm cells are like runners in an epic race, competing against each other for access to the coveted egg at the finish line. The egg, in turn, waits patiently for the winning sperm to pierce its outer membrane, triggering fertilization. This narrative of racing sperm and waiting eggs has persisted through time — and yet, it simply isn't accurate. Scientific research has debunked this idea time and time again.

In her new book "The Stronger Sex: What Science Tells Us about the Power of the Female Body" (Seal Press/Hachette, 2025), science writer Starre Vartan addresses this and other pervasive myths about the female body, highlighting what science actually tells us about differences in biology between the sexes and where gaps in knowledge still exist, in part, due to a historic lack of research focused on females.

Eggs are choosy (but we keep forgetting)

Making all your eggs at once, stress-testing and dumping most of them, and having one available at a time for fertilization is a mammalian adaptation. It represents a shift in reproductive strategy, according to Professor Lynnette Sievert, a biological anthropologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. That shift is away from an earlier, or more ancient method of reproduction, which fish, amphibians, and most reptiles still employ today to great success.

They both make both eggs and sperm continually, in great quantities, and throughout their lifetimes until they die. Female fish and frogs expel their masses of eggs into the water, and the males shoot, deposit, or generally aim their sperm in the eggs' direction. The eggs that get fertilized then develop — or don't, due to environmental conditions, or get eaten by predators. Sea turtles have sex, but still lay hundreds of fertilized eggs at a time and do so until they are elderly, as do oviparous snakes (viviparous snakes give birth to live young).

For all these animals, reproduction is a numbers game. Lots of eggs, lots of sperm, plenty of fertilized eggs and hatchlings, with just a few young surviving to adulthood. In many cases the newly hatched turtles, tadpoles and wee snake-babies are an important food source for other animals who live in their ecosystem, like a biological offering to the greater community.

This more-reproductive-stuff-is-better design is still employed by male humans, but not females.

Related: Do sperm really race to the egg?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Human males still follow the fish pattern. They're still putting out a million sperm. They're not cleaning the sperm, they're not putting out the best sperm, they're just putting out all the sperm just like a fish," Sievert says. She wonders why then, female mammals made a significant shift away from that model. "Why was there never a selection on male sperm and mammals to be like eggs? Something shifted, that separated the sexes," she says. It's an unanswered biological question, but there is one obvious possible answer: Control.

Female mammals house the mechanisms over which eggs (and sperm) are used for reproduction inside their bodies, while amphibians, reptiles, and fish let outside ecological conditions like temperature, predators, salinity and pollutants decide who lives and dies. Both strategies are clearly effective, but why would mammals have shifted away from a successful model?

It could be that longer-lived mammals are able to store epigenetic information about local conditions as they grow, which could influence when and which eggs and sperm are chosen. The choices about who lives and who doesn't are made before or during conception, instead of after, resulting in offspring that are best suited to current conditions.

Why all this trouble to "turn your body into an eggshell," as Cat Bohannon puts it in her book "Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Evolution" — when the eggshell, or other reproductive strategies work so well? It could be explained by a combination of energetics and fine-tuning. By bringing fertilization and growing their young inside the female body, mammals can then use their lived experience (not just conditions at the moment of conception) to affect which traits are selected for. They can do this by controlling both which egg and which sperm are preferred.

All this energy being used at or before the stage of conception means there are fewer fertilized eggs, and fewer babies. When you only have a baby or two at a time, instead of hundreds, it then becomes logical to invest in ensuring it has the best chances of survival — so an egg battle and a female body that's choosy about sperm makes total sense. As do the years of parenting that follow.

That eggs choose sperm is a basic biological fact that has been "discovered" quite a few times over the years. The stubbornness of the "active sperm and waiting egg" story despite the facts highlights how hard it is for humans to accept biological narratives that run counter to our cultural ideas.

As Emily Martin detailed in her memorable paper, we know that it was once the narrative that the sperm was the active party in fertilization, with all the speedy, tough sperm out swimming each other and trying to be the first one to attack the egg's outer membrane to gain entry and deposit their DNA packages.

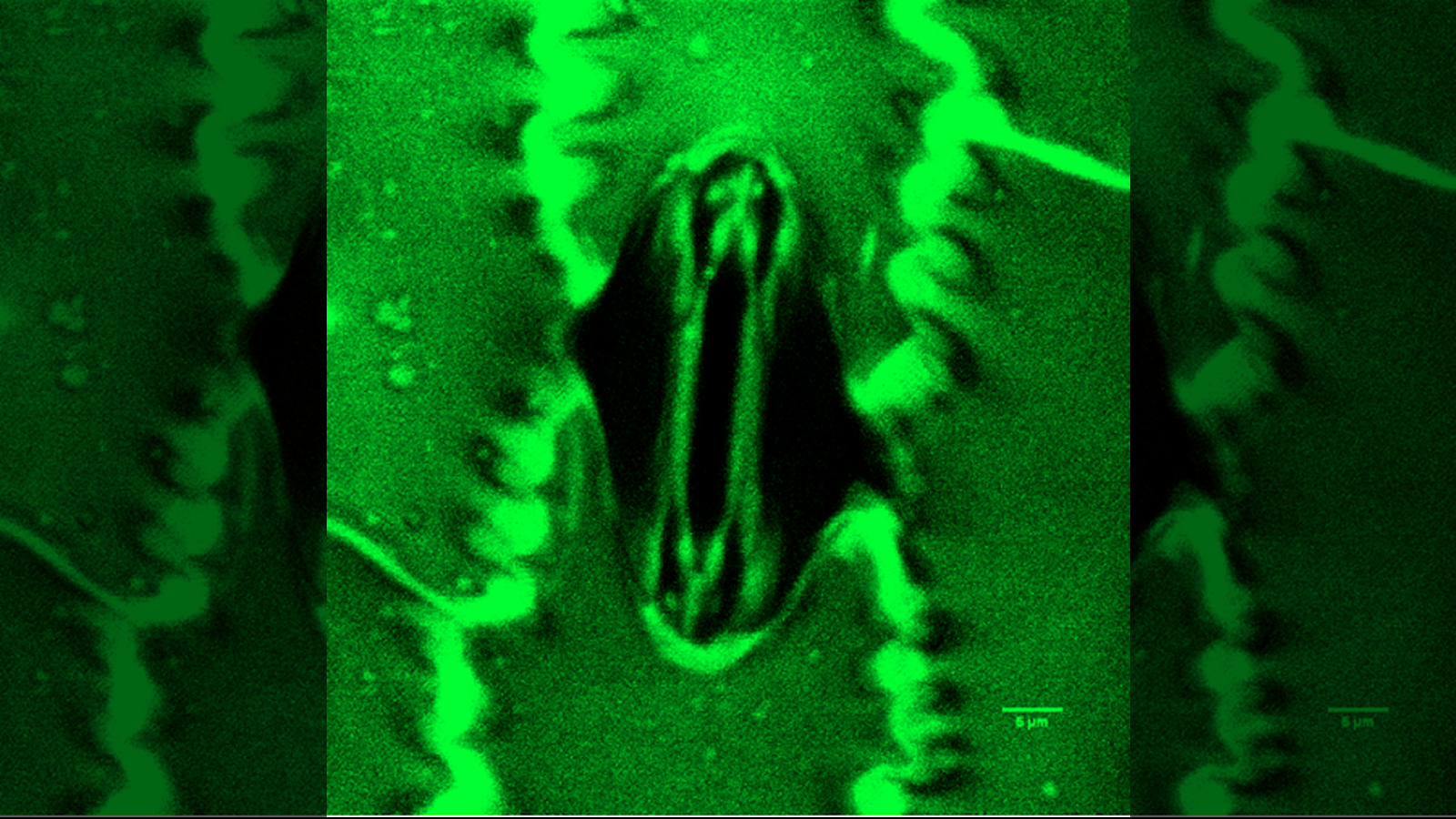

Way back in the mid-1980s, it was first discovered that the egg was actually the active decider in fertilization. The egg does this by using its zona pellucida (a thick protein coat that protects the egg cell) to chemically grab onto sperm, test it, and then reject or admit its DNA into the egg. The sperm, wiggling back-and-forth, can't break even a single chemical bond, but the egg can. Research in the 1990s went on to support the idea, and it's widely accepted.

Yet, over the last 20 years, scientists continue to "discover" this fact. In 2017, Quanta magazine published an article about a researcher whose work was "challenging this dogma" that "the egg is not the submissive, docile cell that scientists long thought it was" and in 2019, a University of Virginia magazine article stated: "The old notion of the egg as a passive partner for sperm entry is out. Instead, the researchers found, there are molecular players on the surface of the egg that bind with a corresponding substance on the sperm to facilitate the fusion of the two." The writer called this an "unexpected discovery."

This "rediscovery" of already known scientific information about the egg and sperm's interaction was covered by a Ms. Magazine article in 2024 about Evelyn Fox Keller, a pioneer in the field of feminist philosophy of science. The passive egg/active sperm idea just wouldn't go away, even in the same journals that published the research that it wasn't true. "One of Fox Keller's key findings was that seemingly neutral assumptions in biology can in fact be gendered. Keller's informed social analysis of the sciences paved the way to approach science as a cultural phenomenon." That researchers and the science press are repeating the same "discoveries" for decades shows just how gendered ideas stick to the culture, and can hold science back.

The newest evidence shows that not only does an egg decide which sperm it wants to admit, the egg may be attracting or repelling different sperm even before they make it to the egg.

In 2020, scientists at Stockholm University collaborating with colleagues at the University of Manchester found that eggs release a chemical that can attract sperm as it makes its journey. They also found that different eggs attract different varieties of sperm — not all eggs attracted the same sperm. The eggs sometimes attracted sperm that was not their partner's.

They figured this out by obtaining reproductive material from couples who gave them permission to at an IVF clinic in Manchester, U.K. "Each experimental block comprised the follicular fluid and sperm samples from a unique set of two couples, exposing sperm from each male to follicular fluid from their partner and a non-partner," the researchers wrote of their methods.

Chemosensory communication between eggs and sperm allows "female choice and bias fertilizations toward specific males," the researchers wrote. What are the egg's criteria? It's unknown at this point. It could be selecting higher-quality sperm or sperm that's more genetically compatible in some way. "This shows that interactions between human eggs and sperm depend on the specific identity of the women and men involved," one of the researchers told Labroots. He went on to say that the choice of sperm was entirely up to the egg.

The science shows that contrary to some cultural stories, the menstrual cycle is highly sensitive to conserve energy; eggs go to war each month so that only the strongest survive; that winner egg sends out come-hither signals to sperm it likes; and then it chooses which sperm to unite with to make a possible new human being.

So much for the inherent weakness of women's bodies and the passive female reproductive system.

In interviews with dozens of researchers from biology, anthropology, physiology, and sports science, plus in-depth conversations with runners, swimmers, wrestlers, woodchoppers, thru-hikers, firefighters, and more, "The Stronger Sex" squashes outdated ideas about women’s bodies. It's a celebration of female strength that doesn't argue "down with men" but "up with us all."

Starre Vartan writes about science, nature, and the female body — especially the parts that are strong, misunderstood, or totally ignored. Her work’s been published in National Geographic, Scientific American, Undark, Aeon, and New Scientist, among other outlets. Her latest book, "The Stronger Sex: What Science Tells Us about the Power of the Female Body," was published in July 2025. She started her career as a geologist and later earned an MFA in nonfiction from Columbia University.

- Nicoletta LaneseChannel Editor, Health

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus