How do archaeologists figure out the sex of a skeleton?

Archaeologists can estimate a person's sex with 95% accuracy, but many experts are focused on what can be learned about humans outside the male/female gender binary.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When archaeologists find ancient human remains, they often try to determine if the person was male or female based on their bones.

So how do archaeologists figure out the sex of the individual from their skeleton, and how accurate are their techniques?

"Overall, we're looking at shape and size differences between the sexes," Sean Tallman, a biological anthropologist at Boston University, told Live Science, but "no one method is 100% accurate."

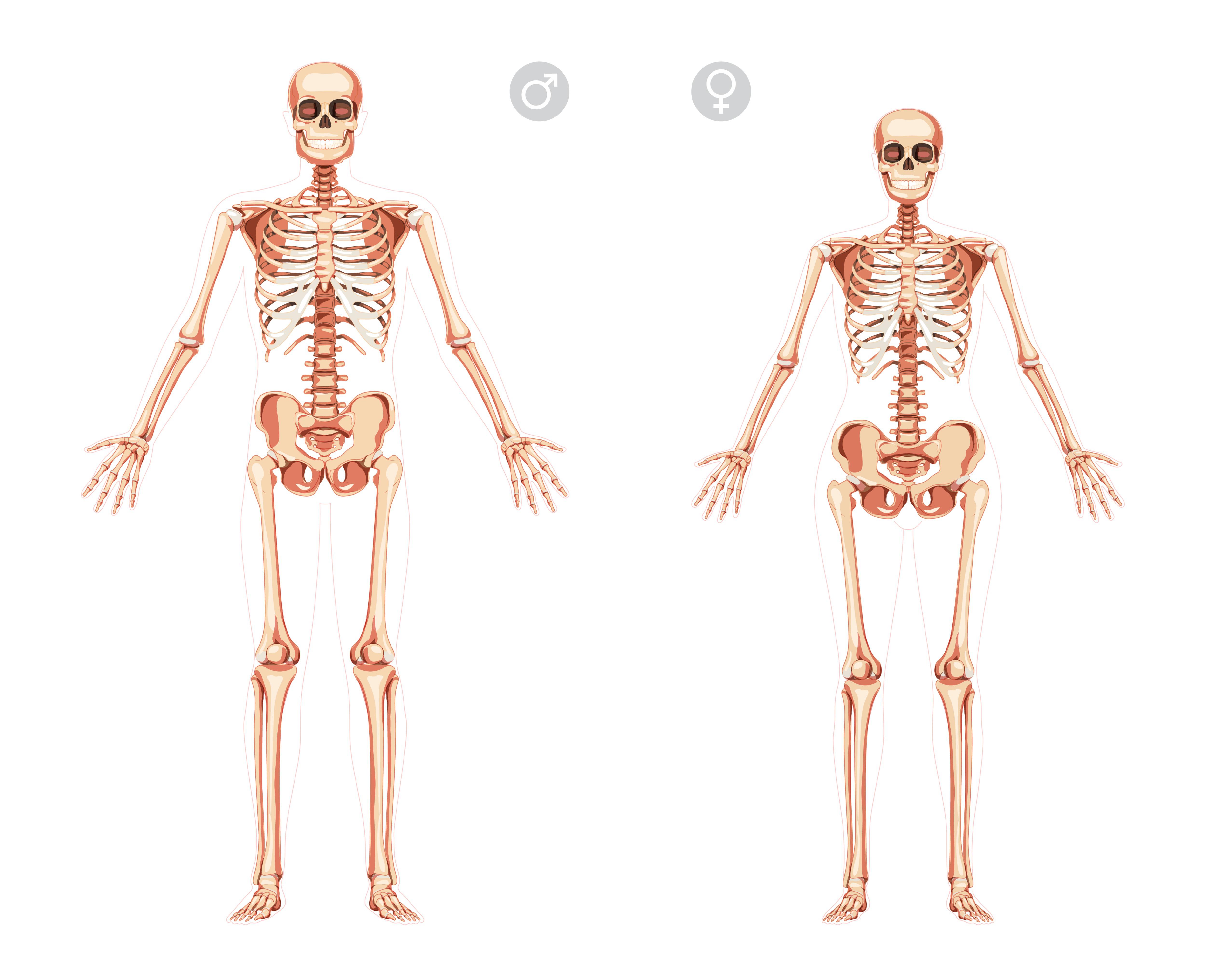

Archaeologists often take measurements of long, slender bones, like the femur and tibia (which make up the leg), and then use statistical methods to predict the person's sex.

"On average, males are about 15% larger than females," Kaleigh Best, a biological anthropologist at Western Carolina University, told Live Science. But many variables — such as diet, genetics, disease and environment — go into body size, so there can be wide variation even among people of the same sex.

Related: What is the maximum number of biological parents an organism can have?

Most measurement-based techniques assume that males are larger and taller than females, and sex predictions from measurements are 80% to 90% accurate. But if the skeleton's pelvis is well preserved, simply looking at certain features of it is generally a more accurate method than relying on measurements of leg bones.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The main method of estimating the individual's sex from the pelvis is called the Phenice method, named after the anthropologist who proposed it in the 1960s. Differences in the shape of the pubic bone at the front of the pelvis correlate with a person's sex — a taller pubic bone, for example, is more likely to be from a male individual, while a wider one is more likely to be from a female. A well-trained archaeologist can predict the sex of a skeleton with about 95% accuracy with this method.

Ancient DNA analysis is also an accurate chromosomal sex estimation method, in which scientists identify the sex-linked variant of a gene related to tooth enamel production. This technique now reaches about 99% accuracy, even in archaeological skeletons. However, since DNA degrades over time, not every archaeological skeleton can be analyzed in this way.

In spite of this high accuracy rate, many archaeologists say that estimating whether a past person was male or female based on their bones alone may miss other aspects of biological sex, which is a result of the interplay between chromosomes, hormones, gonads and gametes. (Gender, in contrast, is a cultural construct that reflects self-identity, societal roles and pressures.)

"Sex is not binary, but it may be bimodal," Donovan Adams, a biological anthropologist at the University of Central Florida, told Live Science. Bimodal in this context means that if you were to plot sex on a graph, there would be two "humps" for male and female on each end of the graph. But the overlap between the two groups in the middle would represent people who are described as intersex.

"About 1.7% of the population is some form of intersex," Virginia Estabrook, a biological anthropologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, told Live Science, which is "slightly less than 1 in 50 people."

Some examples of intersex conditions include congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), an over-production of male hormones that can make female genitalia look ambiguous at birth; Klinefelter syndrome, or XXY sex chromosomes, resulting in small testes and enlarged breasts in people born male; androgen insensitivity syndrome, in which a person may be born with female-type external genitalia but no internal reproductive organs; and 5α-Reductase 2 deficiency; in which an infant that appears female at birth later develops a penis and testes. And people may have other forms of sex chromosome mosaicism, with XX chromosomes in some cells and XY in others.

For example, Estabrook studied the skeleton of Revolutionary War hero Casimir Pulaski, who died in battle in 1779. His skeleton showed several bony traits that are more typical in female-patterned growth and development, Estabrook said, but historical records clearly show he lived his life as a man. One possible explanation for this discrepancy may be CAH, in which chromosomally female infants have genitals that look more like male genitals. People with CAH produce increased androgens and can grow facial hair.

The case of the intersex general is relatively unique, Estabrook said, "because ordinarily when we encounter skeletons in archaeology, we don't know who these people were."

Understanding who an ancient person was can be stymied not just by the limitations of osteological sex estimation but also by the variable of gender.

Most aspects of a person's identity — from the sports team they support to the gender they adopt — are not something they are born with. "You have to perform identity all throughout your life," Adams said. Those life experiences, including behaviors like wielding a bow-and-arrow or kneeling to grind grain that are often gendered, may leave marks on an ancient skeleton that can muddy the waters — especially because we only imperfectly understand past cultures.

The complexity of both sex and gender means that sometimes archaeologists' interpretations are wrong.

At Pompeii, for example, DNA analysis revealed that a set of skeletons assumed to be a mother and her biological child were actually a man and unrelated child, and in 2019, a Viking burial replete with weapons was found to be chromosomally female rather than male.

Though DNA analysis can dramatically increase the accuracy of chromosomal sex assignment, that doesn't necessarily mean archaeologists have solved the problems of estimating sex from ancient human remains.

"It's really hard to separate ourselves from that binary system," Tallman said, "but there's a ton of overlap between females and males."

Estabrook agreed. "Every way that we try to put a strict, solid line of demarcation on biological sex, there are people who fall outside of those lines," she said.

Another issue is that archaeologists still lack information on intersex conditions because there hasn't been much research into the potentially 1-in-50 people who have one.

"Future work will be greatly affected by the availability of federal funding to do this type of research," Tallman said, "and that could limit these nuanced perspectives that we need to interpret behavior and biology from skeletal remains and from archaeological sites."

Scientific advances have made it easier to determine limited aspects of sex from ancient skeletons, Best said, but figuring out a person's identity from their skeleton "is actually a lot more complicated than we once thought it was."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus