Was This Famous Revolutionary War Hero Intersex?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

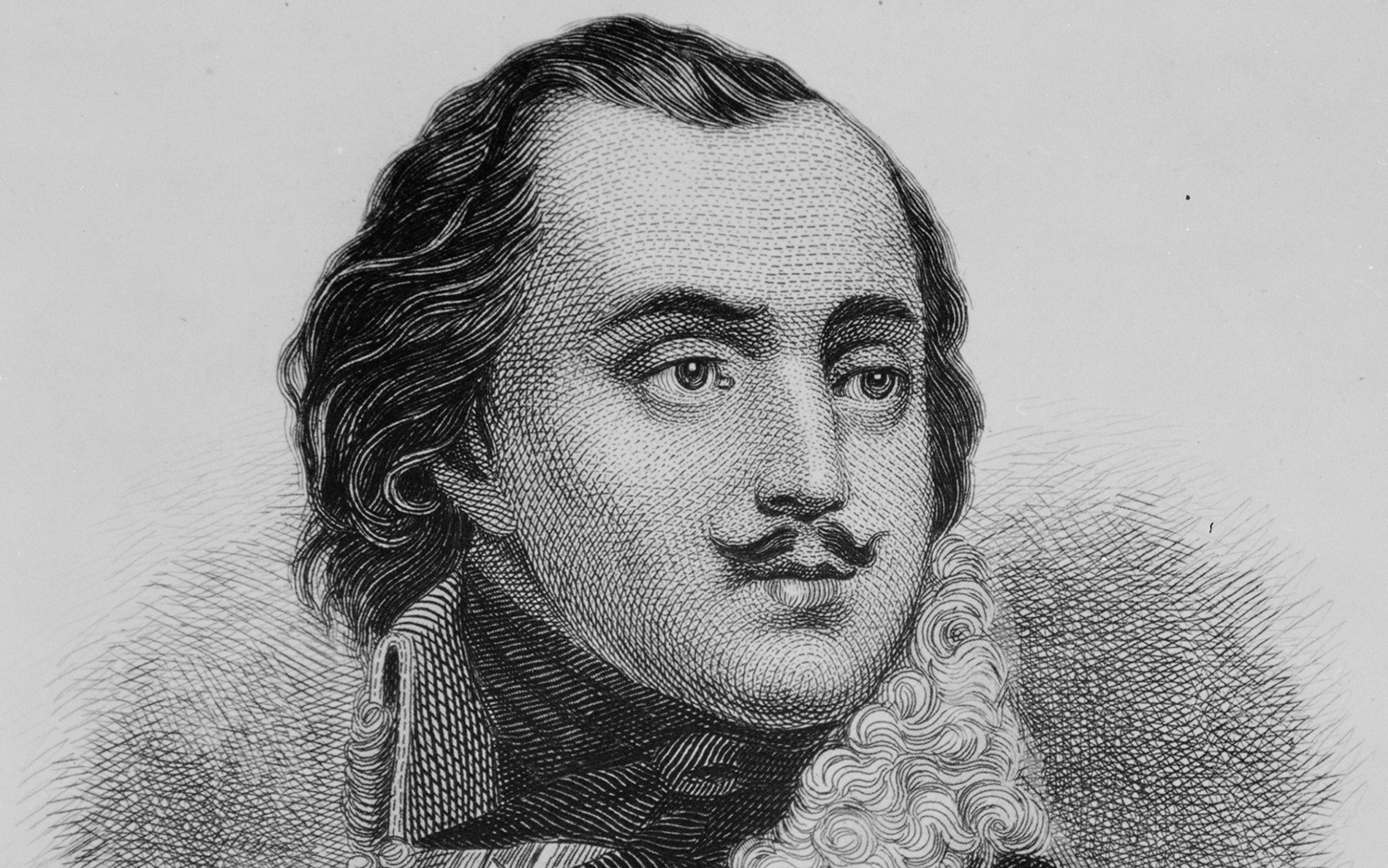

Revolutionary War hero Casimir Pulaski was a dashing young officer who served under George Washington. But a new examination of his remains reveals that he wasn't exactly the gentleman that he appeared to be.

Pulaski, an exiled Polish nobleman, founded America's first cavalry division. He died in battle in 1779 and his remains were entombed inside a monument in Savannah, Georgia, in 1854. But when the tomb was opened more than a century later, experts made a startling discovery: Some features of the skeleton were female.

At that time, scientists were unsure if the body was Pulaski's or that of an unknown woman whose remains were mistakenly placed in Pulaski's tomb. However, new DNA analysis confirms that the skeleton belongs to Pulaski, raising intriguing questions about the general's gender. [The Truth About Genderless Babies]

Details of this incredible story were recently described in "The General Was Female?," an episode in the series "America's Hidden Stories" that premiered yesterday (April 8) on the Smithsonian Channel.

Born in Poland in 1745, Pulaski's military expertise fueled his rise to the role of Brigadier General during America's struggle for independence. He formed a legion that combined cavalry and infantry, called the Pulaski Legion; the generalis known as "The Father of the American Cavalry," according to the National Parks Service.

When the Pulaski monument in Savannah was opened in 1996, experts determined that the skeleton inside was female based on the shape of the pelvis and features in the skull, "such as a delicate midface, with the jaw at more of an obtuse angle," Virginia Estabrook, an assistant professor of anthropology at Georgia Southern University, told Live Science.

But did that mean that Pulaski was actually a woman — or was the body not Pulaski's? Experts conducted genetic tests, comparing DNA from the skeleton with DNA collected from a deceased Pulaski relative. Though the forensic team's results were inconclusive, the body was reburied in 2006 as Pulaski's, Estabrook said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A portrait of the Revolutionary War general Count Casimir Pulaski, engraved by H.B. Hall and published in 1871. Credit: National Archives at College Park

Recently, Estabrook and other experts revisited this historic mystery, analyzing mitochondrial DNA by using a database not available in 2006. They found that DNA from Pulaski and from a maternal relative matched each other more closely than DNA of 27,000 other genetic profiles in the database. This strongly suggested that the two were related — and that the remains in the monument were Pulaski's, Estabrook said.

What's more, the skeleton also preserved known details from Pulaski's life, such as height and build; an old heel injury; and wear in the hip sockets consistent with long-term horseback riding.

Pulaski was almost certainly not a woman living secretly as a man; the general's entire life was conducted as a male identity, and he was christened Casimir — a man's name — as an infant, Estabrook said. However, the researchers proposed something that was not seriously considered when the skeleton was examined 15 years ago: the possibility that Pulaski was intersex, possessing both male and female characteristics.

Intersex is a blanket term for a number of conditions in which development patterns don't all fit neatly into exclusively male or female categories. For instance, babies that are genetically female (two X chromosomes) may have an enlarged clitoris that resembles a penis, while babies that are genetically male (one X and one Y chromosome) may have an abnormally small penis and no testicles, according to the Mayo Clinic.

For Pulaski, one possible explanation could be a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), which can cause females to develop genitals that look more male than female, Estabrook said. Increased androgen production from CAH could also cause someone who was chromosomally female to have a slightly receding hairline and facial hair — as evident on Pulaski in portraits of the general.

Many cultures recognize more than two genders, and some include as many as five, according to Estabrook. Yet remains in archaeological sites are typically interpreted as either male or female, even when a body is buried with gendered objects that aren't consistent with the skeleton's biological sex. Such was the case of the so-called Viking warrior woman, who appeared to be biologically female and was buried with an array of weapons that are usually found in the graves of men.

"What we haven't really thought about is that maybe some of these individuals may have been some form of intersex as well," Estabrook said.

- Men vs. Women: Our Key Physical Differences Explained

- Why Is Pink Associated with Girls and Blue with Boys?

- Photos: Viking Warrior Is Actually a Woman

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus