Science history: Sophie Germain, first woman to win France's prestigious 'Grand Mathematics Prize' is snubbed when tickets to award ceremony are 'lost in the mail' — Jan. 9, 1816

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Milestone: Prize for theory of elastic waves awarded

Date: Jan. 9, 1816 (some sources say Jan. 8)

Where: Paris

Who: Sophie Germain

In January 1816, the secretary general of the Paris Academy of Sciences sent Marie-Sophie Germain a strange letter.

In it, he acknowledged that she had won the institute's prestigious "Grand Mathematics Prize" for her mathematical work describing how sound waves travel across 2D surfaces. And yet, the letter offered no congratulations, noted condescendingly that she was the only entrant, and admitted that she had not received tickets to attend the prize ceremony set to occur two days later. He grudgingly acknowledged that, if needed, handwritten tickets could be hastily produced.

Germain did not attend the ceremony.

"The class of mathematical and physical sciences of the Institute held its public session today, a very large assembly that attracted without doubt those desiring to see virtuoso of a new kind, Miss Sophie Germain, to whom the prize for elastic membranes was to be awarded. The expectation of the public was disappointed: the young lady did not go to take the trophy that no one of her gender has ever received in France," the newspaper Journal des Débats reported about the event that day.

The award was the culmination of a decade of work by Germain, a self-taught polymath. Born to a wealthy merchant's family, she became interested in math while reading books in her father's library during a period of seclusion during the French revolution.

Her parents were not pleased with her "unladylike" pursuit. They banked the fires that kept the house toasty and took away her warm clothes, hoping that she'd be too cold and uncomfortable to study. But when they went to sleep, she'd grab candles and cover herself in quilts to continue her math research. She taught herself number theory and calculus that way.

When the École Polytechnique opened in 1794, women were barred from attending, but the notes from lectures were publicly available. She began reading those notes and submitting answers to problems from the lectures under the pseudonym "Antoine August LeBlanc." Under her pseudonym, Germain also began corresponding with some of the leading mathematicians of her day, including Carl Friedrich Gauss and Joseph-Louis Lagrange.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

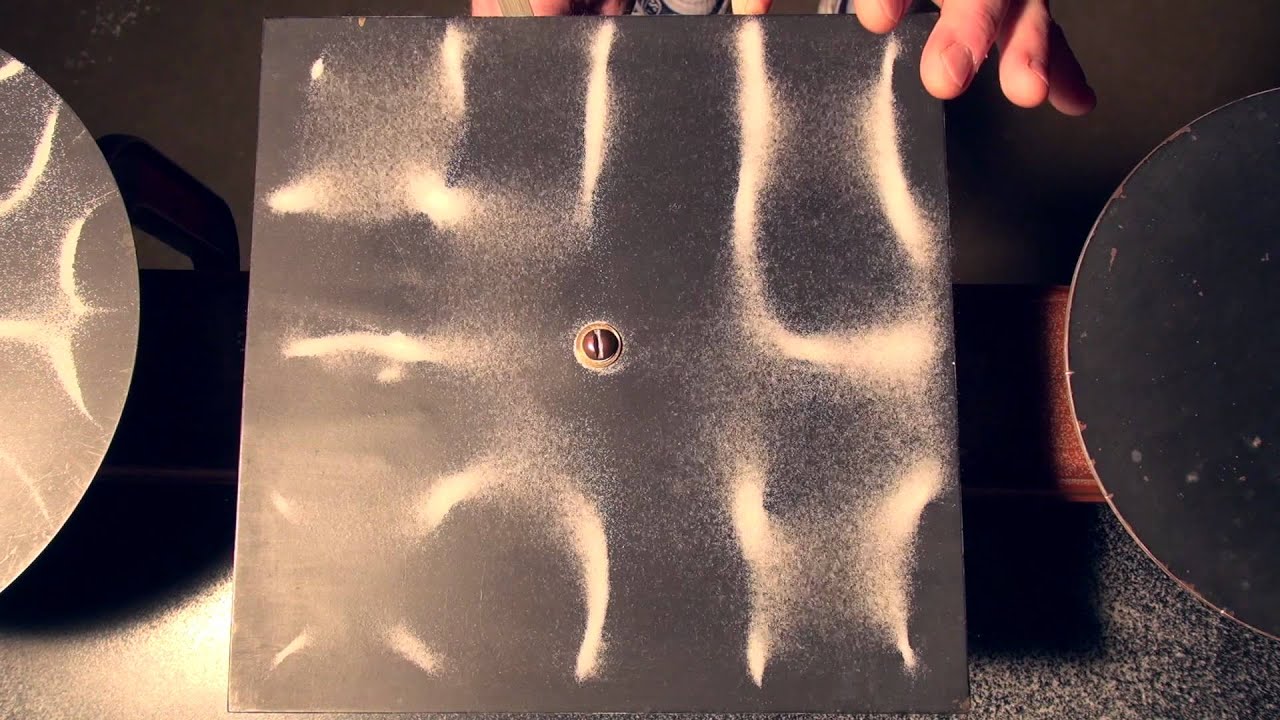

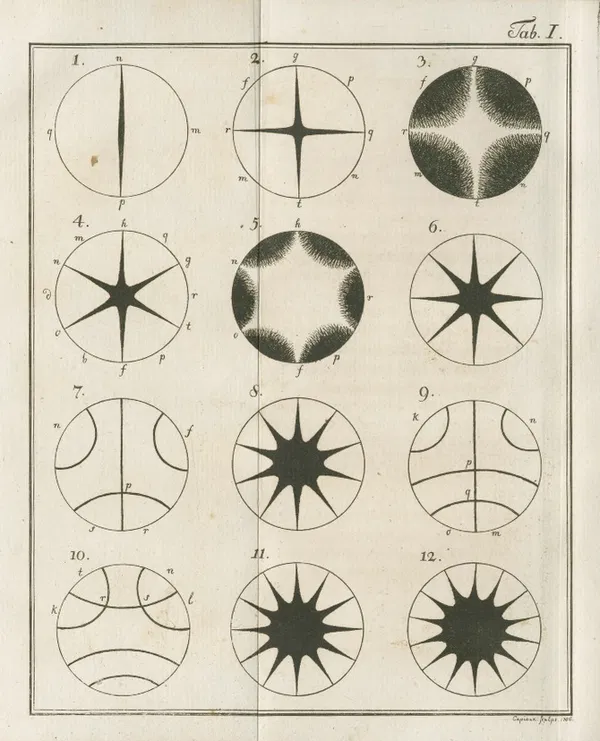

Around 1806, she became intrigued by the physics behind a perplexing experiment. In his 1787 book, physicist and musician Ernst Chladni, often called the "father of acoustics," described a phenomenon in which a person can sprinkle sand across a glass plate and then drag a violin bow across various surfaces and edges. Not only could the plate be played like a violin, but varied geometric patterns formed in the sand depending on how the plates were bowed.

The French institute had offered a prize three years running to mathematically describe the "Chladni figures" that formed. No one else bothered to attempt a solution, with most believing the existing math of the day insufficient to explain the phenomenon.

Germain, however, submitted her proposed solutions all three years. Her third proposal, submitted in 1816, was titled "Research on the Vibrations of Elastic Plates." Though "awkward and clumsy" given the math available at the time, it was still a brilliant insight into the subject of 2D harmonic oscillation, or stably moving waves.

Germain ultimately decided to skip the ceremony because she felt the committee didn't sufficiently respect her work. For instance, her leading rival, Siméon Poisson, was part of the award committee and refused to discuss the problem with her or talk with her in public. Not all of Germain's contemporaries were so dismissive, however; Lagrange and Gauss strongly supported her work.

"But when a woman, because of her sex, our customs and prejudices, encounters infinitely more obstacles than men in familiarizing herself with their knotty problems, yet overcomes these fetters and penetrates that which is most hidden, she doubtless has the most noble courage, extraordinary talent, and superior genius," Gauss wrote when he discovered her gender.

Germain would continue with her solitary math research for decades.

Her work with French mathematician Adrien-Marie Legendre was a major advance in the proof of Fermat's Last Theorem, which states that no three positive integers (a, b, c) can satisfy the equation aⁿ + bⁿ = cⁿ for any integer value of n greater than 2.

Germain showed that Fermat's Last Theorem held for a special class of prime numbers, now called Germain primes, in which both p and 2p+1 are prime. Her work formed the foundation for the eventual, complete solution produced by Andrew Wiles in 1994. Nonetheless, Germain's theorem was mentioned only in a footnote in Legendre's work.

In 1831, her longtime correspondent and mentor Gauss pushed for the University of Göttingen to give Germain an honorary degree. She died of breast cancer a few weeks before she could be given the award.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus