'Proof by intimidation': AI is confidently solving 'impossible' math problems. But can it convince the world's top mathematicians?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

At a secret meeting in 2025, some of the world's leading mathematicians gathered to test OpenAI's newest large language model, o4-mini.

Experts at the meeting were amazed by how much the model's responses sounded like a real mathematician when delivering a complex proof.

"I've never seen that kind of reasoning before in models," Ken Ono, a professor of number theory at the University of Virginia said at the time. "That's what a scientist does."

But was the artificial intelligence (AI) model being given more credit than it deserved? And do we run the risk of accepting AI-derived proofs without fully understanding them?

Ono acknowledged that the model might be giving convincing — but potentially incorrect — answers.

"If you say something with enough authority, people just get scared," Ono said. "I think o4-mini has mastered proof by intimidation; it says everything with so much confidence."

In the past, confidence and the appearance of a good argument were good signs because only the best mathematicians could make convincing arguments, and their reasoning was usually sound. That has changed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Unfortunately, the AI is much better at sounding like they have the right answer than actually getting it … right or wrong; they will always look convincing,"

Terry Tao, UCLA mathematician

"If you were a terrible mathematician, you would also be a terrible mathematical writer, and you would emphasize the wrong things," Terry Tao, a mathematician at UCLA and the 2006 winner of the prestigious Fields Medal, told Live Science. "But AI has broken that signal."

Naturally, mathematicians are beginning to worry that AI will spam them with convincing-looking proofs that actually contain flaws that are difficult for humans to detect.

Tao warned that AI-generated arguments might be incorrectly accepted because they look rigorous.

"Unfortunately, the AI is much better at sounding like they have the right answer than actually getting it … right or wrong; they will always look convincing," Tao said.

He urged caution on the acceptance of AI '"proofs." "One thing we've learned from using AIs is that if you give them a goal, they will cheat like crazy to achieve the goal," Tao said.

While it may seem largely abstract to ask whether we can truly "prove" highly technical mathematical conjectures if we can't understand the proofs, the answers can have significant implications. After all, if we can't trust a proof, we can't develop further mathematical tools or techniques from that foundation.

For instance, one of the major outstanding problems in computational math, dubbed P vs. NP, asks, in essence, whether problems whose solutions are easy to check are also easy to find in the first place. If we can prove that, we could transform scheduling and routing, streamline supply chains, accelerate chip design, and even speed up drug discovery. The flip side is that a verifiable proof might also compromise the security of most current cryptographic systems. Far from being arcane, there is real jeopardy in the answers to these questions.

Proof is a social construct

It might shock non-mathematicians to learn that, to some extent, human-derived mathematical proofs have always been social constructs — about convincing other people in the field that the arguments are right. After all, a mathematical proof is often accepted as true when other mathematicians analyze it and deem it correct. That means a widely accepted proof doesn't guarantee a statement is irrefutably true. Andrew Granville, a mathematician at the University of Montreal, suspects there are issues even with some of the better-known and more scrutinized human-made mathematical proofs.

There's some evidence for that claim. "There have been some famous papers that are wrong because of little linguistic issues," Granville told Live Science.

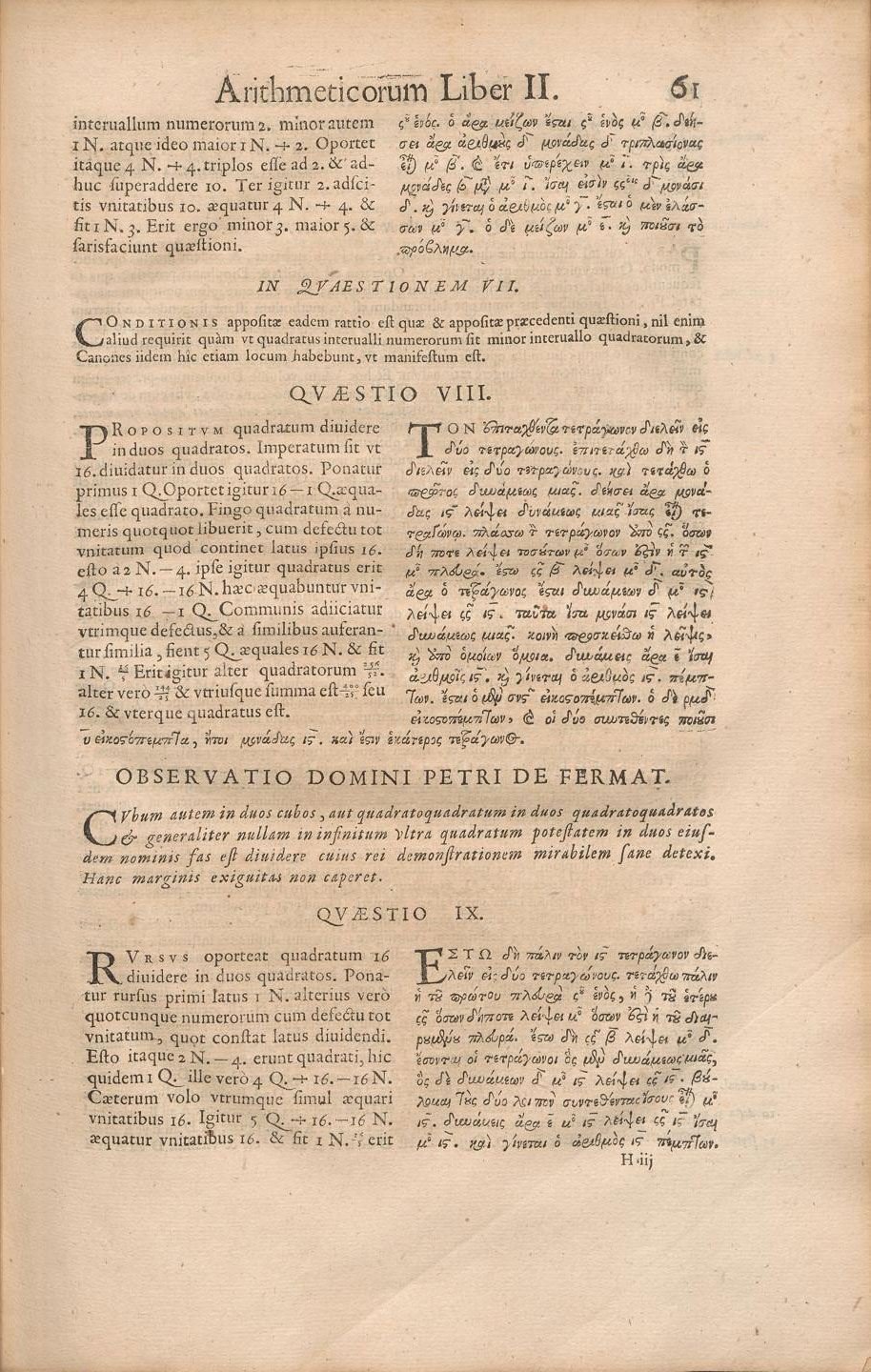

Perhaps the best-known example is Andrew Wiles' proof of Fermat's last theorem. The theorem states that although there are whole numbers where one square plus another square equals a third square (like 32+42=52), there are no whole numbers that make the same true for cubes, fourth powers, or any other higher powers.

Wiles famously spent seven years working in almost complete isolation and, in 1993, presented his proof as a lecture series in Cambridge, to great fanfare. When Wiles finished his last lecture with the immortal line "I think I'll stop there," the audience broke into thunderous applause and Champagne was uncorked to celebrate the achievement. Newspapers around the world proclaimed the mathematician's victory over the 350-year-old problem.

During the peer-review process, however, a reviewer spotted a significant flaw in Wiles' proof. He spent another year working on the problem and eventually fixed the issue.

But for a short time, the world believed the proof was solved, when, in fact, it hadn't been.

Mathematical verification systems

To prevent this sort of problem—where a proof is accepted without actually being correct—there's a move to shore up proofs with what mathematicians call formal verification languages.

These computer programs, the best known example of which is called Lean, require mathematicians to translate their proofs into a very precise format. The computer then goes through every step, applying rigorous mathematical logic to confirm the argument is 100% correct. If the computer comes across a step in the proof it doesn't like, it flags it and doesn't let go. This encoded formalization leaves no room for the linguistic misunderstandings that Granville worries have plagued previous proofs.

Kevin Buzzard, a mathematician at Imperial College London, is one of the leading proponents of the formal verification. "I started in this business because I was worried that human proofs were incomplete and incorrect and that we humans were doing a poor job documenting our arguments," Buzzard told Live Science.

In addition to verifying existing human proofs, AI, working in conjunction with programs like Lean, could be game-changing, mathematicians said.

"If we force AI output to produce things in a formally verified language, then this, in principle, solves most of the problem," of AI coming up with convincing-looking, but ultimately incorrect proofs, Tao said.

"There are papers in mathematics where nobody understands the whole paper. You know, there's a paper with 20 authors and each author understands their bit. Nobody understands the whole thing. And that's fine. That's just how it works."

Kevin Buzzard, Imperial College London mathematician

Buzzard agreed. "You would like to think that maybe we can get the system to not just write the model output, but translate it into Lean, run it through Lean," he said. He imagined a back-and-forth interaction between Lean and the AI in which Lean would point out errors and the AI would attempt to correct them.

If AI models can be made to work with formal verification languages, AI could then tackle some of the most difficult problems in mathematics by finding connections beyond the scope of human creativity, experts told Live Science.

"AI is very good at finding links between areas of mathematics that we wouldn't necessarily think to connect," Marc Lackenby, a mathematician at the University of Oxford, told Live Science.

A proof that no one understands?

Taking the idea of formally verified AI proofs to its logical extreme, there is a realistic future in which AI will develop "objectively correct" proofs that are so complicated that no human can understand them.

This is troubling for mathematicians in an altogether different way. It poses fundamental questions about the purpose of undertaking mathematics as a discipline. What is ultimately the point of proving something that no one understands? And if we do, can we be said to have added to the state of human knowledge?

Of course, the notion of a proof so long and complicated that no one on Earth understands it is not new to mathematics, Buzzard said.

"There are papers in mathematics where nobody understands the whole paper. You know, there's a paper with 20 authors and each author understands their bit," Buzzard told Live Science. "Nobody understands the whole thing. And that's fine. That's just how it works."

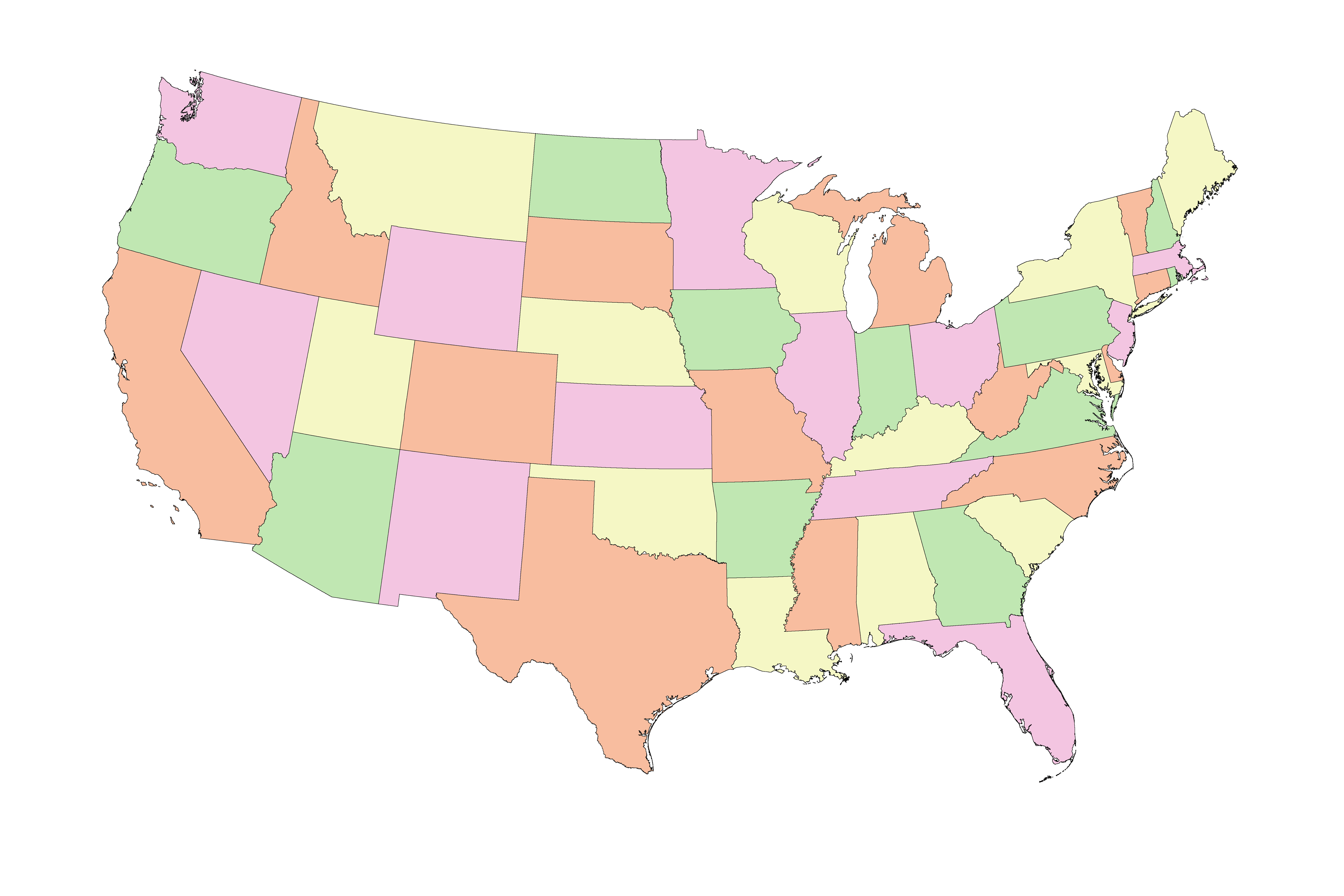

Buzzard also pointed out that proofs that rely on computers to fill in gaps are nothing new. "We've had computer-assisted proofs for decades," Buzzard said. For instance, the four-color theorem states that if you have a map divided into countries or regions, you'll never need more than four distinct colors to shade the map such that neighboring regions are never the same colors.

Almost 50 years ago, in 1976, mathematicians broke the problem into thousands of small, checkable cases and wrote computer programs to verify each one. As long as the mathematicians were convinced there weren't any problems with the code they'd written, they were reassured the proof was correct. The first computer-assisted proof of the four-color theorem was published in 1977. Confidence in the proof built gradually over the years and was reinforced to the point of almost universal acceptance when a simpler, but still compute-aided, proof was produced in 1997 and a formally verified machine-checked proof was published in 2005.

"The four-color theorem was proved with a computer," Buzzard noted. "People were very upset about that. But now it's just accepted. It's in textbooks."

Uncharted territory

But these examples of computer-assisted proofs and mathematical teamwork feel fundamentally different from AI proposing, adapting and verifying a proof all on its own — a proof, perhaps, that no human or team of humans could ever hope to understand.

Regardless of whether mathematicians welcome it, AI is already reshaping the very nature of proofs. For centuries, the act of proof generation and verification have been human endeavors — arguments crafted to persuade other human mathematicians. We're approaching a situation in which machines may produce airtight logic, verified by formal systems, that even the best mathematicians will fail to follow.

In that future scenario — if it comes to pass — the AI will do every step, from proposing, to testing, to verifying proofs, "and then you've won," Lackenby said. "You've proved something."

However, this approach raises a profound philosophical question: If a proof becomes something only a computer can comprehend, does mathematics remain a human endeavor, or does it evolve into something else entirely? And that makes one wonder what the point is, Lackenby noted.

Kit Yates is a professor of mathematical biology and public engagement at the University of Bath in the U.K. He reports on mathematics and health stories, and was an Association of British Science Writers media fellow at Live Science during the summer of 2025.

His science journalism has won awards from the Royal Statistical Society and The Conversation, and has written two popular science books, The Math(s) of Life and Death and How to Expect the Unexpected.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus