Science history: Russian mathematician quietly publishes paper — and solves one of the most famous unsolved conjectures in mathematics — Nov. 11, 2002

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Milestone: Poincaré conjecture solved

When: Nov. 11, 2002

Where: St. Petersburg, Russia

Who: Grigori Perelman

On a cold day in November, a man living quietly in Russia posted a paper to a public server.

Published by "Grisha Perelman" and titled "The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications," it was the foundation for one of the most important math proofs.

The paper was the first of three published over the next year solving the long-standing Poincaré conjecture, a hypothesis posed nearly a century earlier by Henri Poincaré.

In simple terms, Poincaré hypothesized that if you were to take any kind of 3D space — from a cat to the Empire State Building — and draw a 2D loop on it, if you can shrink that loop down to a point without breaking either the loop or the shape, then the space is mathematically equivalent to a sphere.

Proving this conjecture was crucial to topology, the mathematical study of shapes. Mathematician Stephen Smale had solved the conjecture in five dimensions in 1961, earning math's prestigious Fields Medal in the process. But the 3D case proved the most intractable.

In the 1980s, Richard Hamilton, a mathematician at Columbia University, proposed solving the conjecture using a math technique called Ricci flow, which had been useful for Einstein's theory of general relativity, as well as string theory.

In 2006, New York Times reporter Dennis Overbye likened the Ricci flow technique to using heat from a hair dryer to smooth out shrink-wrap. Similarly, the Ricci flow could smooth out wrinkles and curvature and reduce a complicated shape to a more fundamental one.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ricci flow worked to simplify roundish shapes to spheres, but singularities — points of infinite density — kept cropping up in more complicated shapes. Topologists can perform a kind of "surgery" to excise these singularities, but there was still a possibility that the singularities would keep emerging forever. Researchers were stuck.

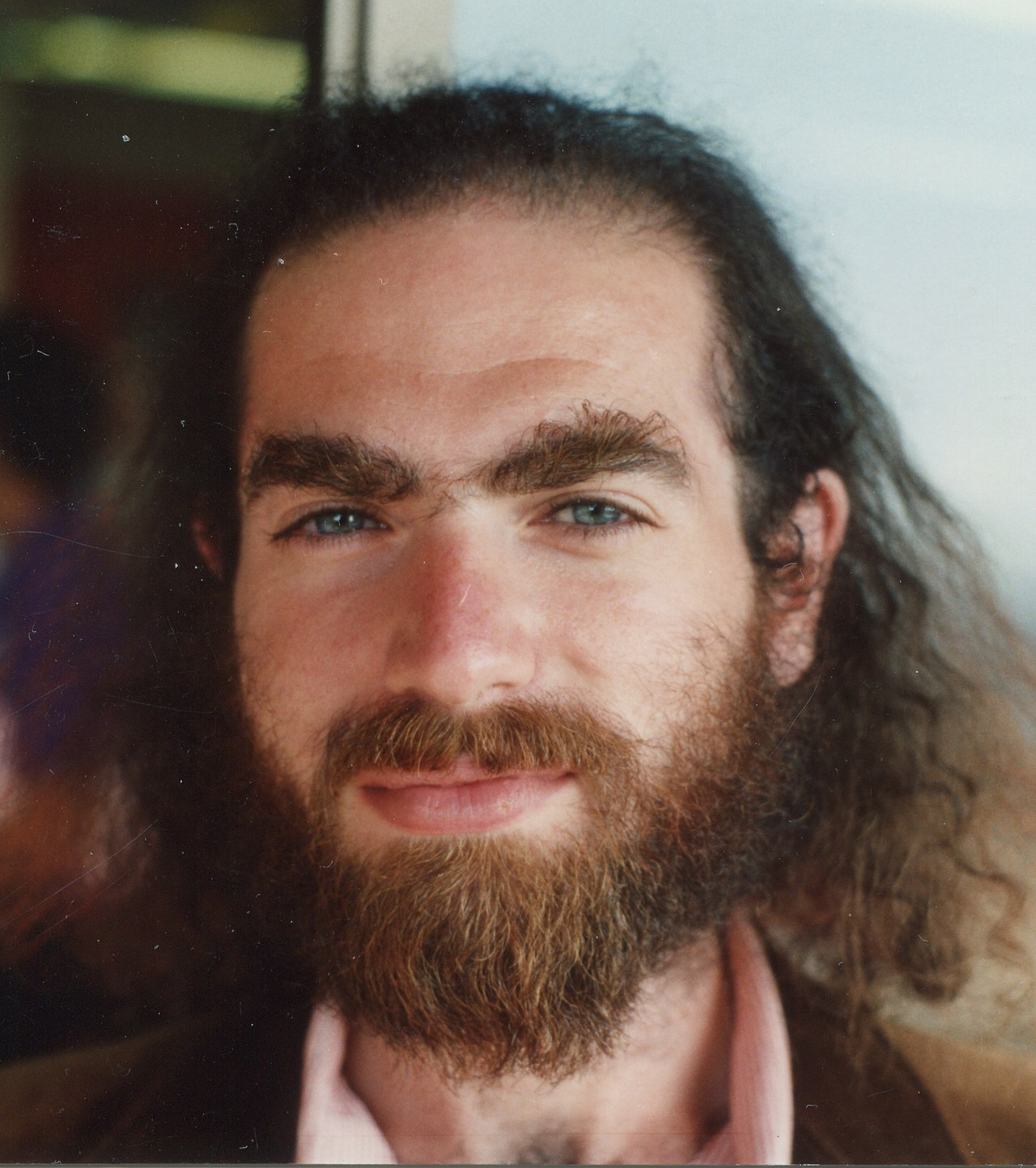

Perelman's work solved the singularity problem. Perelman (whose first name is Grigori, also spelled Grigory; Grisha was a nickname) had spent the prior decade doing postdoctoral research in the U.S. at several institutions. In the mid-1990s, he turned down very prestigious math fellowships in the U.S. and Europe, returned to St. Petersburg, and took a position at the Steklov Institute of Mathematics.

The friendly-but-shy and "unworldly" mathematician "looked like Rasputin, with long hair and fingernails," and he told colleagues he enjoyed hiking in the woods around St. Petersburg, hunting for mushrooms, Robert Greene, a mathematician at UCLA, told Overbye in 2006. He seemed completely uninterested in wealth or material success, his colleagues reported.

Perelman receded into obscurity after he returned to Russia in the mid- to late 1990s, and many of his colleagues thought he had left mathematics altogether.

Then Perelman published his 2002 paper. Over the next year, he published two more papers and gave a series of talks at several East Coast colleges, explaining his process. Then, he receded into the background once more.

Perelman's work showed that all of the singularities actually reduced to simple shapes, like spheres or tubes, and that if you could follow the Ricci process to its end, you would find the 3D shape reduced to a sphere. He had proved the Poincaré conjecture, but it would take another few years for mathematicians to wade through his brilliant, original and highly technical proofs and confirm that the great topographical problem had, indeed, been solved.

In 2006, mathematicians John Morgan and Gang Tian published a 473-page paper showing that Perelman's work, building on Hamilton's, did in fact prove the elusive conjecture.

Perelman was offered the prestigious Fields Medal and the Clay Millennium math prize, which came with a $1 million award. He turned them down, reportedly due to objections about how credit was given for solving the problem.

Perelman resigned from his position at the Steklov Institute in 2005 and has since ferociously avoided the limelight. It's unclear whether he is still working on math in his St. Petersburg apartment, where as of the early 2010s, his neighbors said he cared for his elderly mom.

When a reporter tried to contact him in 2010, he rejected an interview, saying, "You are disturbing me. I am picking mushrooms."

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus