'No easy explanation': Scientists are debating a 70-year-old UFO mystery as new images come to light

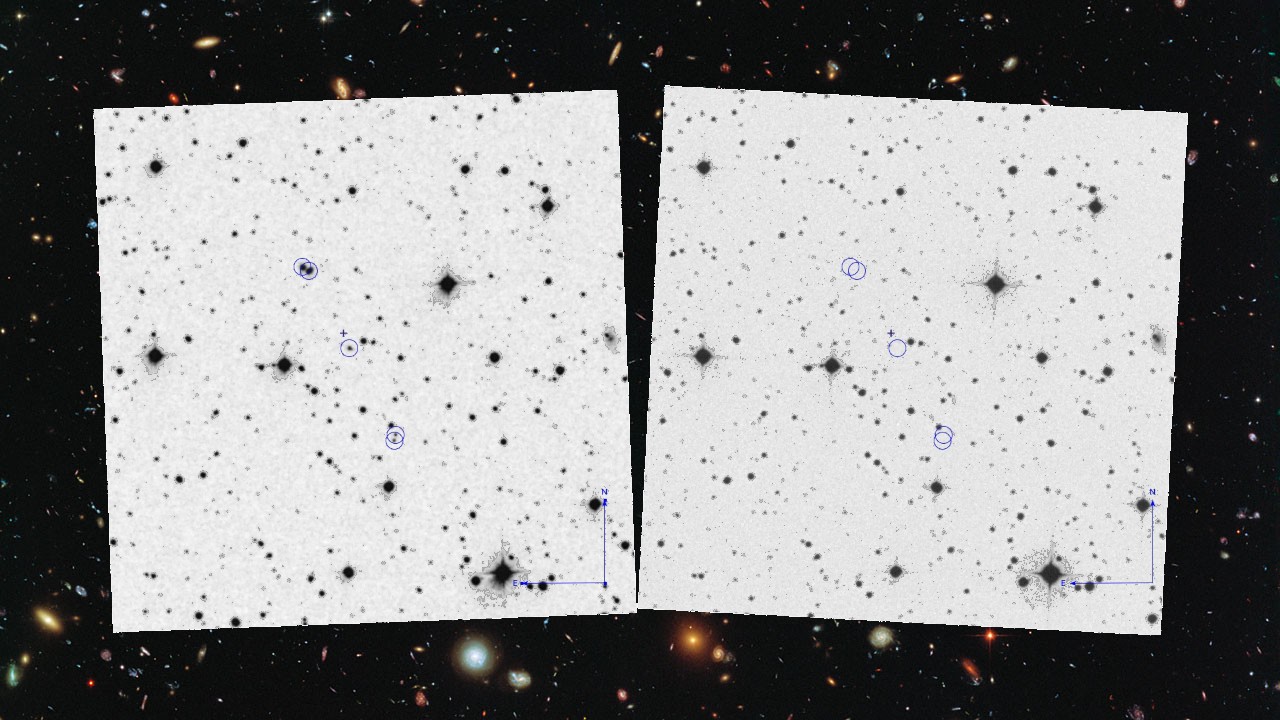

Two new peer-reviewed papers claim thousands of unexplained light flashes in vintage Palomar telescope images show statistical ties to nuclear tests and UFO reports. Not everyone agrees with the paper's conclusion.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

More than 70 years ago, astronomers at the Palomar Observatory in California photographed several star-like flashes that appeared and vanished within an hour — years before the first satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched into orbit.

New peer-reviewed research revisiting those midcentury sky plates reports that these fleeting points of light, called transients, appeared on or near dates of Cold War nuclear weapons tests and coincided with a spike in historical UFO reports. Could these things all be related? Researchers are trying to find out.

While such flashes can sometimes be traced to natural phenomena such as variable stars, meteors or instrumental quirks, several of the Palomar events share distinctive features — including some sharp, point-like shapes that appear to line up in straight rows — that the authors of the new research say defy known natural or instrumental causes.

"We've ruled out some of the prosaic explanations, and it means we have to at least consider the possibility that these might be artificial objects from somewhere," study co-author Stephen Bruehl, an anesthesiologist at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Tennessee who is interested in UFOs, told Live Science. Bruehl co-authored two recent papers with Beatriz Villarroel, an astronomer at the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics in Sweden.

"If it turns out that transients are reflective artificial objects in orbit — prior to Sputnik — who put them there, and why do they seem to show interest in nuclear testing?" Bruehl added.

Not all researchers agree with this interpretation of the images, however — with some experts noting that technological restrictions of the time make this data very hard to interpret with any certainty. Michael Garrett, director of the University of Manchester's Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics in the U.K. who was not involved with the new studies, praised Villarroel's team for their creative use of archival data but cautioned against interpreting these results too literally.

"My main worry is not the quality of the research team but the quality of the data at their disposal," he said. Before Sputnik, the data are poor — especially the anecdotal UFO, or UAP (Unidentified Anomalous Phenomenon) reports, which Villarroel's team acknowledges it did not assess for validity.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The scientific method is well suited to investigating such anomalies, but it takes time, replication and patience," Garrett told Live Science. "I suspect that with better data, these apparent correlations would go away."

Vanishing lights in the sky

Transient objects are a recurring phenomenon in astronomy. Modern sky surveys such as the Zwicky Transient Facility in California and the Pan-STARRS in Hawaii have already detected thousands of these fleeting events, and the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory is expected to identify millions each night over the next decade.

Many of these transients have been successfully linked to known astrophysical processes, including sudden flares from comets and asteroids, explosive deaths of stars, variability in accreting black holes, and neutron-star mergers that produce kilonova afterglows.

To search for such events in the pre-space-age sky, the new research examined digitized images from the first Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS-I), conducted between 1949 and 1958. That survey relied on about 2,000 photographic glass plates, each coated with a light-sensitive emulsion that reacted to incoming light, preserving an imprint of stars, galaxies and other celestial objects. These were manually loaded into the Samuel Oschin Schmidt Telescope for 50-minute exposures that captured broad stretches of the northern sky, and were later scanned and converted into a digital archive.

Villarroel's team examined 2,718 days of survey data and found transient sky events on 310 nights, with as many as 4,528 flashes appearing on a single day across multiple locations but absent from images taken immediately before or after the events, and from all later sky surveys.

When compared with the UFOCAT database of historical UFO reports, the researchers found that transients were 45% more likely to occur within 24 hours of aboveground nuclear tests conducted by the U.S., Soviet Union and Great Britain, and that each additional UAP report on a given day corresponded to an 8.5% rise in transients.

The analysis, published Oct. 20 in the journal Scientific Reports, describes these as "associations beyond chance" between transients, nuclear testing and UAP reports. A companion study the team published Oct. 17 in the journal Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific suggests that some transients appeared in aligned groups and dropped by about 30 percent in sky regions within Earth's umbral shadow — a pattern the authors argue is best explained by sunlight glinting off unknown reflective objects in high, potentially geosynchronous, orbit.

According to the researchers, this finding echoes long-standing speculations that extraterrestrials might be drawn to human nuclear activity, though the authors emphasize that the data do not prove any causal link.

But what if it’s the opposite? A more straightforward explanation, some experts say, is that the flashes, and perhaps some of the reported UFOs, were by-products of the nuclear detonations themselves. Michael Wiescher, a nuclear astrophysicist at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, told Scientific American that such explosions can inject metallic debris and radioactive dust into the upper atmosphere, where they might appear as brief, star-like bursts of light through a telescope.

Villarroel and Bruehl said they considered that possibility but countered that radiation-induced glows or fallout contamination would produce diffuse smudges or streaks, not the star-like points seen on Palomar's sky plates. And if the flashes were fragments of bomb casings hurled into orbit, those objects would need to reach roughly 22,000 miles (35,000 kilometers) above Earth, where modern geostationary satellites reside, to appear motionless over a 50-minute exposure.

Such a scenario seems implausible "unless a miracle occurred," Bruehl told Live Science. "There's no easy explanation for what these transients are and why they show up at nuclear tests."

The imperfect past

Several other astronomers suggest that the mystery likely lies not in the skies but in imperfect photographic plates and error-prone records of the time.

Robert Lupton, an astronomer at Princeton University who develops algorithms to extract meaning from optical data and was not involved with the papers, noted that astronomy has a long history of misinterpreting apparent alignments — including early debates over quasars, when astronomers once thought their apparent pairings in the sky meant they were physically connected, only to later learn they were chance alignments.

"The thing that's hard is to know what the anomalies in the data really look like, and the number of other weird things that we could have seen," Lupton told Live Science. "I thought that using pre-Sputnik data was clever, but hard."

Apparent alignments like those seen in the Palomar Observatory data may stem from imperfections in the photographic material itself, said Nigel Hambly, a survey astronomer at the University of Edinburgh in the U.K. who examined this issue in a 2024 paper. Spurious linear features, he said, can arise from mundane causes — diffraction spikes from bright stars that look like lines, dust, hair and other debris adhered to the emulsion that mimic aligned transients. In some cases, scratches introduced during the copying or digitization of old photographic plates can also create such artifacts, he said.

These problems are especially common when researchers work with copies rather than the originals, as was the case with Villarroel's team, because flaws can persist through generations of reproductions, Hambly said.

A turning point in UFO studies?

Researchers interviewed for this story agree that independent analyses are essential, and several proposed reexamining the same historical data and other archives of scanned plates from observatories active before 1957, ideally from the Northern Hemisphere and with complete, time-series images like those from the Palomar Mountain. Revisiting the original Palomar plates themselves and conducting a microscopic "forensic" examination could help determine whether the reported transients truly appear on the originals or were introduced later, Hambly added.

Inspecting the plates by eye can often reveal the difference between a genuine detection and a spurious blemish in the emulsion "at a level of detail that is lost in the digital scans, even with very high-resolution imaging," Hambly said.

Whether these mysterious flashes prove to be evidence of UAPs, classified military technology, or simply artifacts of a bygone imaging process, the ongoing debate underscores how science probes the unknown and tests the extraordinary.

"I suspect that we may eventually look back to see the publication of these results as a turning point for mainstream acceptance of UFOs as a legitimate research topic, worthy of academic scientific investigation and earnest coverage in the media," David Windt, a research scientist at Columbia University who was not involved with the papers, told Live Science.

Editor's note: This article was updated on Dec. 2 to include a description of the authors' companion paper, published Oct. 17.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus