Physicists recreated the first millisecond after the Big Bang — and found it was surprisingly soupy

Scientists saw a quark plowing through primordial plasma for the first time, offering a rare look at the first moments after the Big Bang

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

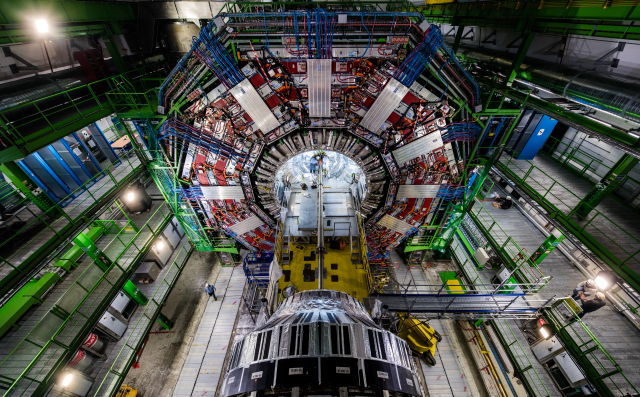

Heavy collisions at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) have revealed the faintest trace of a wake left by a quark slicing through trillion-degree nuclear matter — hinting that the primordial soup of the universe may have literally been more soup-like than we thought.

The new findings from the LHC's Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) collaboration show the first clear evidence of a subtle "dip" in particle production behind a high-energy quark as it traverses quark-gluon plasma — a droplet of primordial matter thought to have filled the universe microseconds after the Big Bang.

A study describing the results, published Dec. 25, 2025, in the journal Physics Letters B, provides a tantalizing look at the universe in its first moments.

Re-creating early-universe conditions in the lab

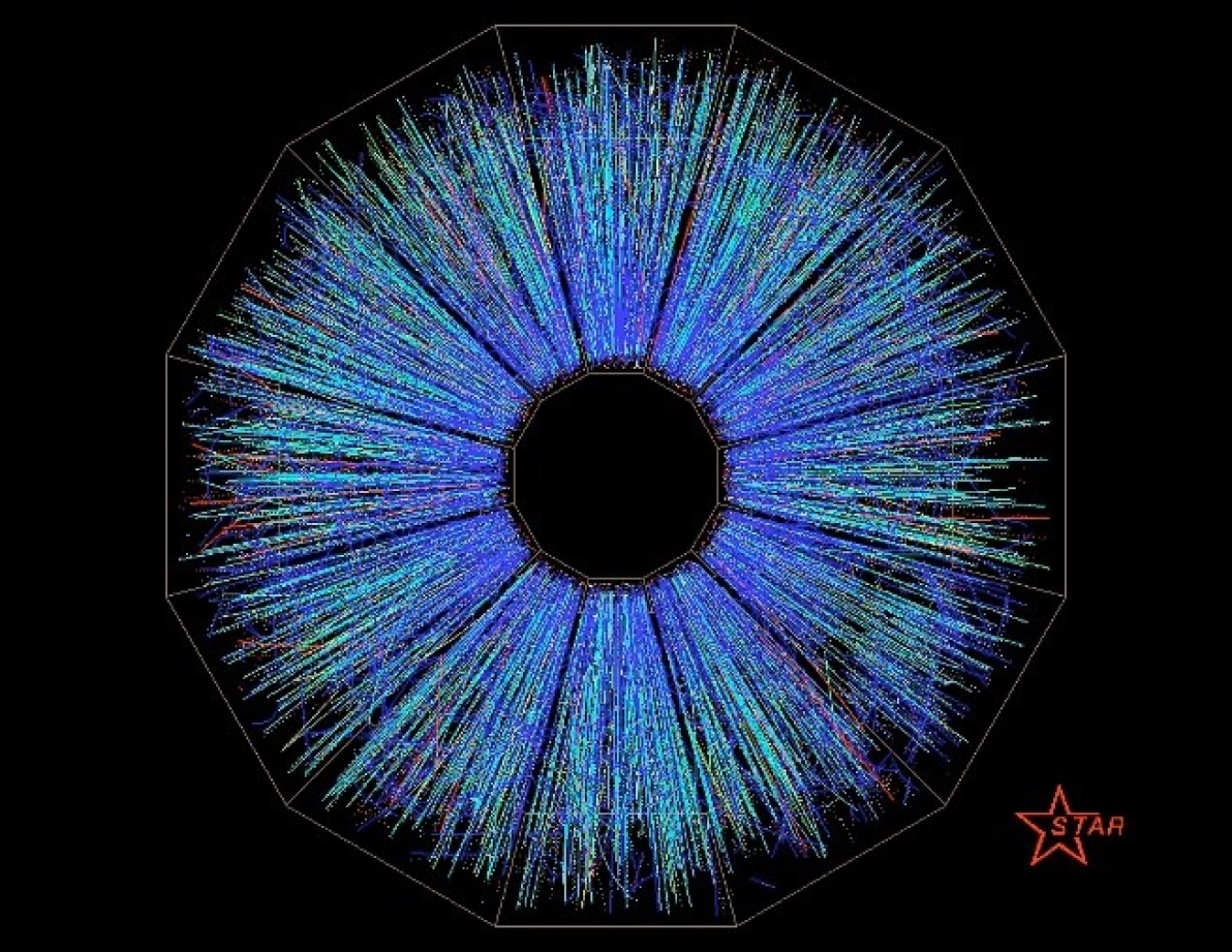

When heavy atomic nuclei collide at near-light speed inside the LHC, they briefly melt into an exotic state known as quark-gluon plasma.

In this extreme environment, "the density and temperature is so high that the regular atom structure is no longer maintained," Yi Chen, an assistant professor of physics at Vanderbilt University and a member of the CMS team, told Live Science via email. Instead, "all the nuclei are overlapping together and forming the so-called quark-gluon plasma, where quarks and gluons can move beyond the confines of the nuclei. They behave more like a liquid."

This plasma droplet is extraordinarily small — about 10-14 meters across, or 10,000 times smaller than an atom — and vanishes almost instantly. Yet within that fleeting droplet, quarks and gluons — the fundamental carriers of the strong nuclear force that holds atomic nuclei together — flow collectively in ways that resemble an ultrahot liquid more than a simple gas of particles.

Physicists want to understand how energetic particles interact with this strange medium. "In our studies, we want to study how different things interact with the small droplet of liquid that is created in the collisions," Chen said. "For example, how would a high energy quark traverse through this hot liquid?"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Theory predicts that the quark would leave a detectable wake in the plasma behind it, much as a boat slicing though water would. "We will have water pushed forward with the boat in the same direction, but we also expect a small dip in water level behind the boat, because water is pushed away," Chen said.

In practice, however, disentangling the "boat" from the "water" is far from straightforward. The plasma droplet is tiny, and the experimental resolution is limited. At the front of the quark's path, the quark and plasma interact intensely, making it difficult to tell which signals come from which. But behind the quark, the wake — if present — must be a property of the plasma itself.

"So we want to find this small dip in the back side," Chen said.

A clean probe with Z bosons

To isolate that wake, the team turned to a special partner particle: the Z boson, one of the carriers of the weak nuclear force — one of the four fundamental interactions, along with the electromagnetic, strong, and gravitational forces — responsible for certain atomic and subatomic decay processes. In certain collisions, a Z boson and a high-energy quark are produced together, recoiling in opposite directions.

Here's where the Z boson becomes crucial. "The Z bosons are responsible for the weak force, and as far as the plasma is concerned, Z just escapes and is gone from the picture," Chen said. Unlike quarks and gluons, Z bosons barely interact with the plasma. They leave the collision zone unscathed, providing a clean indicator of the quark's original direction and energy.

This setup allows physicists to focus on the quark as it plows through the plasma, without worrying that its partner particle has been distorted by the medium. In essence, the Z boson serves as a calibrated marker, making it easier to search for subtle changes in particle production behind the quark.

The CMS team measured correlations between Z bosons and hadrons — composite particles made of quarks — emerging from the collision. By analyzing how many hadrons appear in the "backward" direction relative to the quark's motion, they could search for the predicted wake.

A tiny-but-important signal

The result is subtle. "On average, in the back direction, we see there is a change of less than 1% in the amount of plasma," Chen said. "It is a very small effect (and partly why it took so long for people to demonstrate it experimentally)."

Still, that less-than-1% suppression is precisely the kind of signature expected from a quark transferring energy and momentum to the plasma, leaving a depleted region in its wake. The team reports that this is the first time such a dip has been clearly detected in Z-tagged events.

The shape and depth of the dip encode information about the plasma's properties. Returning to her analogy, Chen noted that if water flows easily, a dip behind a boat fills in quickly. If it behaves more like honey, the depression lingers. "So studying how this dip looks … gives us information on the plasma itself, without the complication of the boat," she said.

Looking back to the early universe

The findings also have cosmological implications. The early universe, shortly after the Big Bang, is believed to have been filled with quark-gluon plasma before cooling into protons, neutrons and, eventually, atoms.

"This era is not directly observable through telescopes,” Chen says. "The universe was opaque back then.” Heavy-ion collisions provide "a tiny glimpse on how the universe behaved during this era," she added.

For now, the observed dip is "just the start," Chen concluded. "The exciting implication of this work is that it opens up a new venue to gain more insight on the property of the plasma. With more data accumulated, we will be able to study this effect more precisely and learn more about the plasma in the near future."

Collaboration, C. (2025). Evidence of medium response to hard probes using correlations of Z bosons with hadrons in heavy ion collisions. Physics Letters B, 140120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2025.140120

Andrey got his B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in elementary particle physics from Novosibirsk State University in Russia, and a Ph.D. in string theory from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. He works as a science writer, specializing in physics, space, and technology. His articles have been published in AdvancedScienceNews, PhysicsWorld, Science, and other outlets.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus