The earliest black holes in the universe may still be with us, surprising study claims

The earliest black holes in the universe may not have disappeared from Hawking radiation after all, new research hints. Instead, they fed on the energy of the ancient cosmos to grow supermassive.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

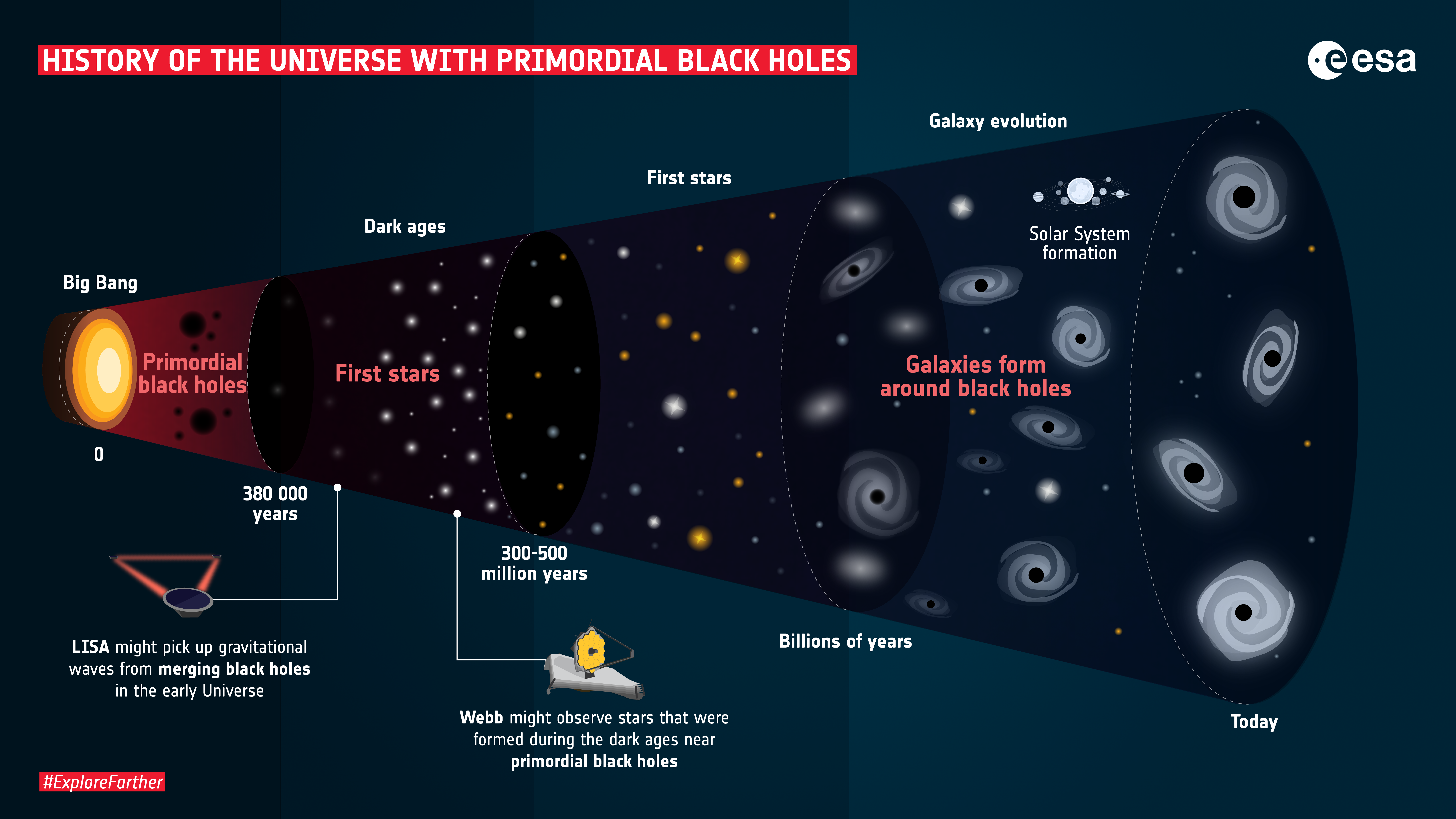

Moments after the Big Bang, the newborn universe was a wild, hot place. In that cosmic soup, primordial black holes — the first black holes in the universe, formed from extremely dense pockets of matter — could quickly take shape.

For ages, our understanding of these objects, especially the smaller ones, was that they eventually just faded away through a quantum process called Hawking radiation. It seemed like a settled fate.

But a new investigation, published in January to the preprint database arXiv, has opened a different path. This research claims that these objects didn't always shrink — sometimes, they could grow, becoming cosmic devourers that absorbed the radiation of the early universe.

Article continues belowThis unexpected appetite doesn't just change the individual destinies of early black holes; it also transforms how we see the universe's past — and, crucially, it alters our search for dark matter, the invisible scaffolding that holds galaxies together.

Hungry newborns

Primordial black holes are a fascinating idea in cosmology. Unlike the usual black holes born from collapsing stars, these objects would have formed in the first moments after the Big Bang, from extreme densities in the universe's initial soup. They could range from microscopic sizes up to masses greater than that of the sun.

For a long time, general relativity told us that these objects, especially the smaller ones, would slowly lose mass through Hawking radiation. They would just evaporate and fade into nothing.

Here's where the story takes a turn. The early universe wasn't just a quiet vacuum around these primordial black holes; it was a thick, hot soup, full of radiation — with photons zipping everywhere.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This new research adds a vital piece to the puzzle: direct absorption of that thermal radiation. If a primordial black hole's collapse efficiency passes a certain point calculated in the new research, it doesn't just slowly evaporate; it starts to feed. These black holes become silent, hungry cosmic devourers, the new study suggests.

This new understanding changes everything about how we picture the early cosmos and the destiny of these ancient objects. Their ability to grow means they can live far longer than we previously thought, leading to extended lifetimes and substantial mass.

If primordial black holes can grow by absorbing radiation, then a much broader range of initial masses could still exist today, acting as the universe's unseen dark matter. The research indicates this expanded range depends heavily on something called the absorption efficiency parameter — a measure of how quickly and efficiently the black hole can feed on matter around it.

For instance, if this parameter is 0.3, the allowed range for a primordial black hole to form and become dark matter expands from 10^16 grams to 10^21 grams. If the parameter is 0.39, then the range is from 5*10^14 grams to 5*10^19 grams. Previously, it was thought that primordial black holes couldn't be this massive and still be responsible for dark matter.

This work makes us rethink a lot about the universe's earliest moments. It forces a fundamental reevaluation of how these objects evolve and their potential to explain the mystery of dark matter. This isn't just a small tweak to a model; it's a new chapter in our cosmic story. We thought we knew the life cycle of these objects, but it turns out, the universe had other plans.

Haque, M. R., Karmakar, R., & Mambrini, Y. (2026). When primordial black holes absorb during the early universe. arXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2601.16717

Black hole quiz: How supermassive is your knowledge of the universe?

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus