Some objects we thought were planets may actually be tiny black holes from the dawn of time

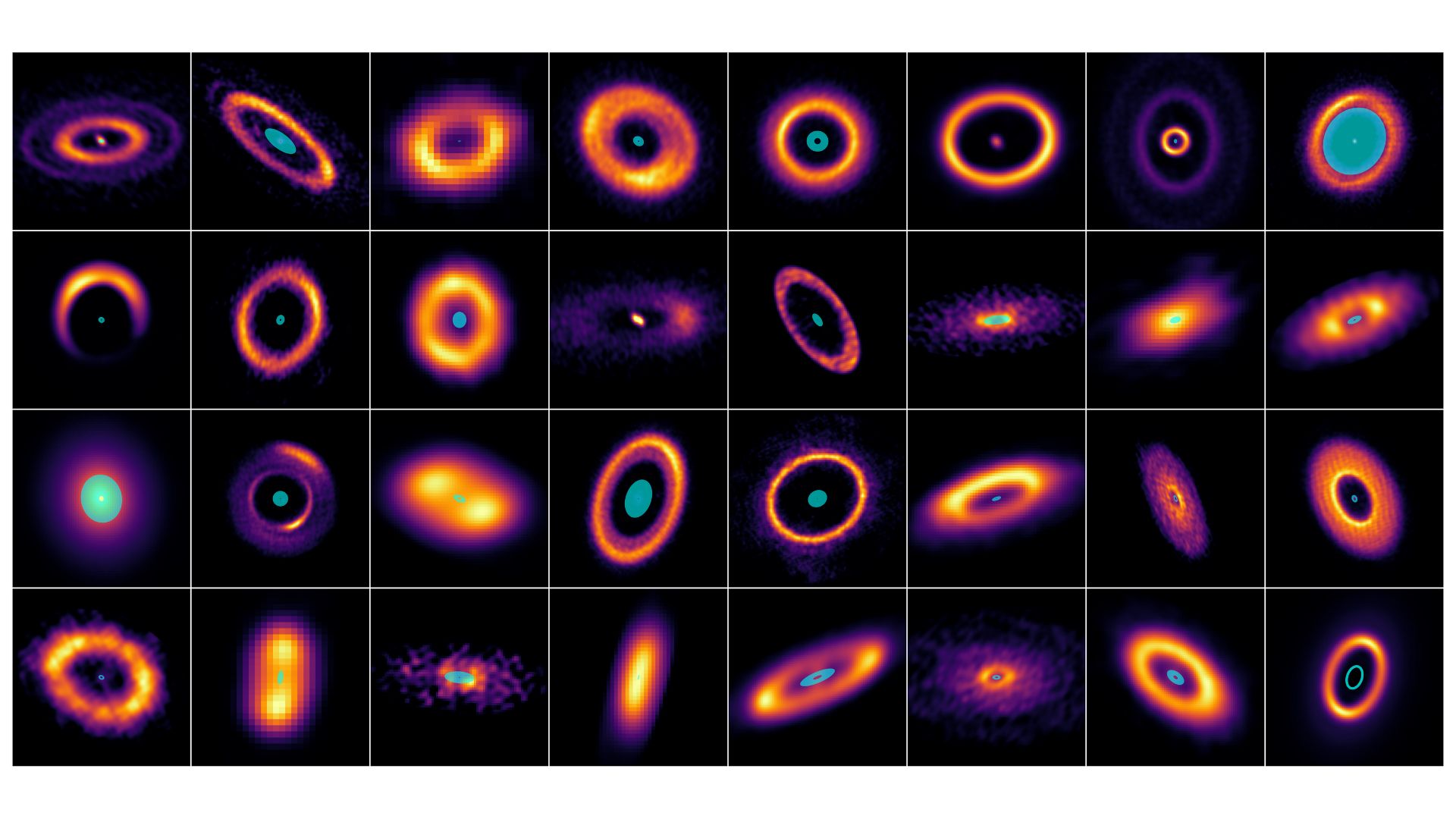

Scientists have discovered more than 6,000 planets beyond our solar system. What if some of them aren't planets at all, but tiny black holes in disguise?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

What if some of the alien worlds we've discovered are not actually planets at all?

Astronomers have spent years cataloging thousands of worlds orbiting distant stars, assuming that if something has the mass of a planet and exerts a gravitational pull on its parent star, it must be a planet.

But there may be a ghostly alternative lurking in the early universe. In a recent paper that was uploaded to the arXiv preprint server but has not been peer-reviewed, researchers suggest that some "exoplanets" we've detected might actually be something far more exotic — primordial black holes.

These are not your garden-variety black holes, born from dying stars. Instead, they are hypothetical leftovers from the Big Bang itself, formed when the newborn universe was a chaotic, high-pressure soup of energy. These "mini" black holes could have the mass of Earth or Jupiter but be the size of a grapefruit.

Our current methods for finding planets are exceptionally good at measuring mass but less so at determining the physical size of a planet. For example, we often use the radial velocity method — a technique that involves watching a star "wobble" because the gravity of an orbiting object is yanking on it. If the wobble is big, the object is heavy. If the wobble is small, the object is light.

But here's the catch: A planet with the mass of Neptune and a black hole with the mass of Neptune produce the exact same wobble.

In an attempt to separate the two, the authors of the new study looked at exoplanets that have been detected via these wobbles but have never been seen crossing the face of their star — a process called a transit. When a planet transits, it blocks some light, telling us its physical size. If an object pulls on a star but never blocks any light, it might be because it is too small to see, or it might be because it is a black hole.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers identified several intriguing suspects, including Kepler-21 Ac, HD 219134 f and Wolf 1061 d. These objects are heavy enough to make their stars wobble, yet they remain invisible to our telescopes. The team pointed to microlensing events — brief flashes of light caused when a massive object passes in front of a distant star and acts like a magnifying glass — as potential hiding spots for these ancient nomads.

The authors admitted that these candidates are merely representative possibilities, rather than a definitive gallery of tiny black holes. Most will likely turn out to be ordinary planets that just happen to have tilted orbits that prevent them from transiting.

The next decade of data from missions like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope — a NASA telescope that will take a broad survey of exoplanets, due to launch as soon as this fall — will be crucial for learning more about these objects. We might catch one evaporating via Hawking radiation, a theoretical process whereby black holes slowly leak energy until they vanish. If so, we might discover that the universe is a lot more crowded with ancient black holes than we ever imagined.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus