Scientists spot 'unprecedented celestial event' around the 'Eye of Sauron' star just 25 light-years from Earth

Scientists watching the nearby Fomalhaut star system have directly seen two protoplanets smash together for the first time. Then, they saw it happen again.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers hoping to observe a planet around a nearby star have witnessed a much rarer "unprecedented celestial event," the team said: The violent aftermath of not one, but two collisions between the rocky building blocks of planets.

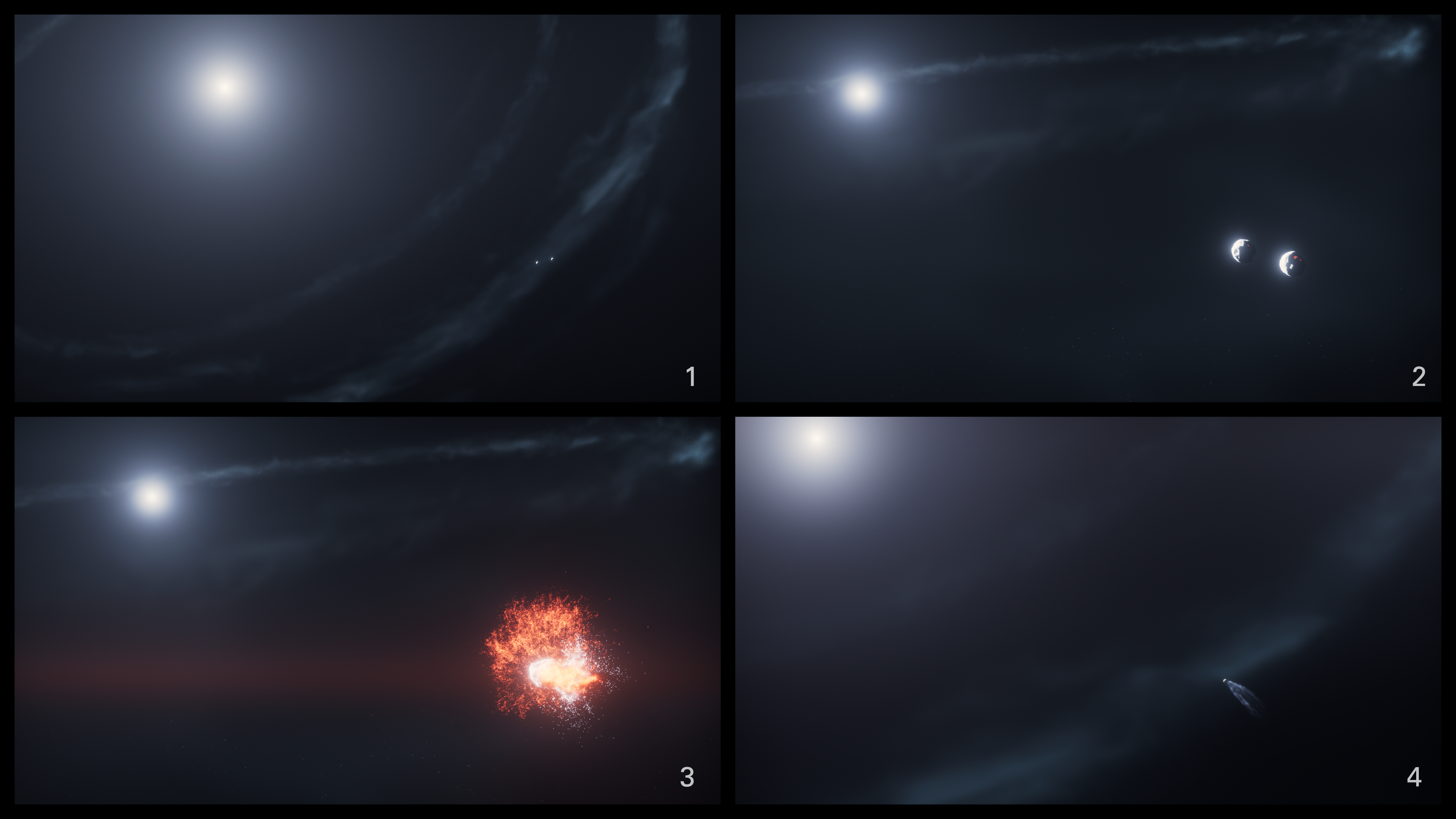

Over the past two decades, astronomers witnessed two separate catastrophic collisions around the star Fomalhaut, located just 25 light-years away in the constellation Piscis Austrinus. The detections occurred after planetesimals (rocky pieces of unformed planets) measuring much larger than the dinosaur-killing asteroid smashed each other into massive clouds of glittering debris.

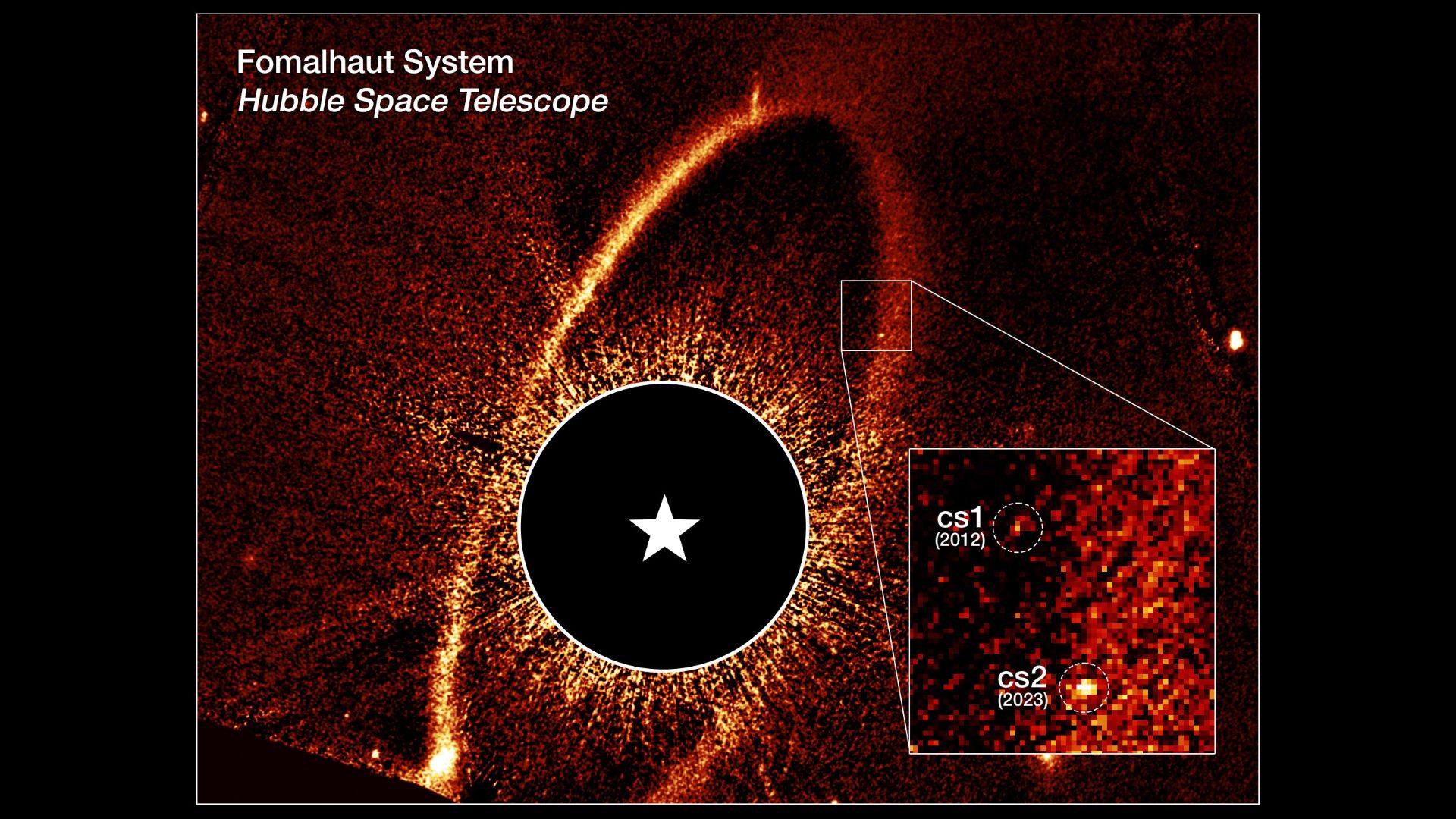

The Fomalhaut system is no stranger to such crashes. It's famously known as the "Eye of Sauron" due to its resemblance to the fiery, all-seeing eye from J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of The Rings franchise. The likeness comes from the spectacular dust belt that surrounds Fomalhaut at a distance of 133 astronomical units (AU), with one AU being equal to 93 million miles (150 million km) — the average distance between the sun and Earth.

Formed from countless rocky, icy collisions, this belt of dust and debris provides a dustier analog of our early solar system as it appeared more than 4 billion years ago, the team said — offering a glimpse of our neighborhood's chaotic infancy, when planets were being created, destroyed, and reassembled.

False planet syndrome

A new study, conducted by an international team of researchers and led by Paul Kalas, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley, described these two collision events in destructive detail to help solve a planetary mystery.

In the early 2000s, astronomers observing the Fomalhaut system spotted a large, luminous object that many assumed to be a dust-covered exoplanet reflecting light. They designated this exoplanet candidate Fomalhaut b.

Yet when this supposed planet blinked out of existence and another bright point of light appeared nearby, all in the span of approximately 20 years, researchers realized they weren't viewing planets, but the shining debris clouds formed by what they call a "cosmic fender bender."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fomalhaut forensics: a history of catastrophic crashes

The two collision events, now known as Fomalhaut cs1 and Fomalhaut cs2, appear to be incredibly serendipitous. Theory suggests that collisions of this size should only happen once every 100,000 years or so, but the Fomalhaut system surprised scientists with two such smash-ups in just 20 years.

Indeed, based on this timeline, the study infers that 22 million similar events may have occurred during the Fomalhaut system's relatively young, 440-million-year-old life so far. Even if one could rewind only the past 3,000 years or so, "Fomalhaut's planetary system would be sparkling with these collisions," Kalas explained in a statement.

Reverse engineering the collisions based on factors like the mass of the debris clouds and the size of the dust grains suggests that Fomalhaut cs1 and cs2 were the result of colliding planetesimals around 37 miles (60 km) in diameter, or around four to six times the size of the asteroid that devastated the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

It's an alien event with a relatable twist: "These larger bodies are like the larger bodies that comprise our own asteroid and Kuiper belts," study co-author Jason Wang, an astronomer at Northwestern University, told Live Science via email.

And there are a lot of these bodies. Based on their reconstruction of the event, the researchers suggest that the Fomalhaut system may host 1.8 Earth masses of these primordial planetesimals. This may amount to about 300 million such bodies, according to a separate statement.

Furthermore, the system holds another 1.8 Earth masses in smaller bodies measuring less than 0.186 miles (0.3 kilometers) across. These relative runts constantly replenish the tiny dust grains, many just a few 10,000ths of an inch in size, that swirl and shimmer in Fomalhaut's dust belt. Without this rocky reservoir, the dust belt would disappear as its grains are blown out of the system by stellar wind or engulfed by its star.

The planet that never was, still may be

Even though Fomalhaut b no longer exists — as a planet, at least — this "planet that never was" may actually still be hiding within the system.

Researchers calculated that, given the specific conditions, there's about a 10% chance that Fomalhaut cs1 and cs2 are not random collisions. Their similar timing and location may point to a hidden influence, such as the ghostly gravitational pull of an unseen exoplanet.

"For example, something — like planets — should be responsible for carving out the planetesimals into a dust belt that we see," Wang told LiveScience. "Additionally, we speculate that the proximity in location of the cs1 and cs2 impact sites may be driven by a planet that preferentially causes planetesimals to collide there."

Playing planetary peek-a-boo

This exoplanetary confusion highlights an important consideration for planet-hunters, and for next-generation facilities like NASA's Habitable Worlds Observatory that are designed to directly image habitable-zone exoplanets in the nearby universe: "Fomalhaut cs2 looks exactly like an extrasolar planet reflecting starlight," explained Kalas.

As a result, this unique study not only informs our ideas about planetary formation, such as collision rates and debris belt mechanics, but can also help astronomers more precisely identify planetary bodies from among all the other shining celestial objects with which the universe continually dazzles us.

Ivan is a long-time writer who loves learning about technology, history, culture, and just about every major “ology” from “anthro” to “zoo.” Ivan also dabbles in internet comedy, marketing materials, and industry insight articles. An exercise science major, when Ivan isn’t staring at a book or screen he’s probably out in nature or lifting progressively heftier things off the ground. Ivan was born in sunny Romania and now resides in even-sunnier California.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus