Every major galaxy is speeding away from the Milky Way, except one — and we finally know why

A vast, flat sheet of dark matter may solve the long-standing mystery of why our neighboring galaxy Andromeda is speeding toward us while our other neighbors are moving away from us.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The structure of the local universe is surprisingly flat, according to new research, and this cosmic quirk may save our Milky Way from colliding with countless other massive, nearby galaxies — except one.

For decades, astronomers have made the puzzling observation that our nearest galactic neighbor, Andromeda, is speeding toward a possible collision with our galaxy, while other nearby galaxies are moving away from us. Now, a new study may finally reveal why: A vast, flat sheet of dark matter is drawing those galaxies into deep space.

Dark matter anchors and attracts visible matter, and the gravitational pull from the far-out dark matter sheet, which lies slightly beyond the bounds of Andromeda and the Milky Way, overwhelms the attraction between our galaxy and other neighboring galaxies, researchers reported in a paper published Jan. 27 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"The observed motions of nearby galaxies and the joint masses of the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy can only be properly explained with this 'flat' mass distribution," the researchers said in a statement.

Future simulations could further explain how gravity sculpts our surroundings and why the local universe looks the way it does.

Going with the flow

The motion of galaxies throughout the expanding fabric of space-time is known as the Hubble flow. It's mathematically described by Hubble's law, named after astronomer Edwin Hubble, who discovered the expansion of the universe in the 1920s. His eponymous law constrains an observational phenomenon: Galaxies are moving away from Earth at speeds that are proportional to their distance. The farther a galaxy is from our vantage point, the faster it seems to be receding.

So why is Andromeda, located 2.5 million light-years away, hurtling toward us at 68 miles per second (110 kilometers per second), while most other large, nearby galaxies are following the flow? Curiously, these receding galaxies appear to resist the immense gravitational attraction of our Local Group, which includes the Milky Way, Andromeda, the Triangulum Galaxy and dozens of gravitationally bound, smaller galaxies.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This universal enigma has endured for more than half a century. In 1959, astronomers Franz Kahn and Lodewijk Woltjer found evidence of dark matter situated around Andromeda and the Milky Way. They calculated that to reverse the initial expansion imparted by the Big Bang, these two galaxies would require a combined mass much greater than all their stars put together.

It turns out that a significant portion of the mass of the Milky Way and Andromeda is contained in dark matter halos that surround each galaxy and facilitate the galaxies' rapid approach toward each other.

However, this attraction does not seem to affect nearby galaxies outside the Local Group, where "material is actually moving away from the Milky Way faster than the Hubble flow," study co-author Simon White, director emeritus of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany, said in a statement.

"Thus, galaxies closer than [roughly 8 million light-years] are moving away from us slower than predicted by Hubble's Law, whereas galaxies farther than [that] are actually receding faster than predicted," White told Live Science via email.

Building a universe from scratch

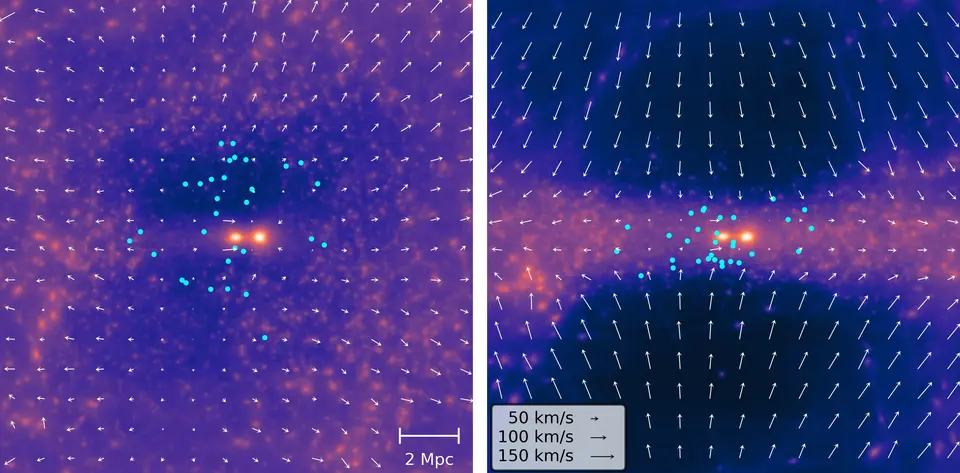

To find out why, the researchers built their own universe. They ran a multitude of simulations to explore the interactions among dark matter, our Local Group, and the receding galaxies just outside it, to a distance of around 32 million light-years.

The simulations modeled the evolution of the local universe from the beginning of space-time, starting with the mass distributions observed in the cosmic microwave background, the oldest light in the cosmos, emitted when the universe was just 380,000 years old. The researchers then had the model reproduce certain salient characteristics observed in nearby galaxies, including the mass, position and velocity of Andromeda and the Milky Way, as well as the positions and velocities of 31 galaxies located just outside the Local Group.

This revealed that the mass just slightly beyond the Local Group, including both dark matter and visible matter, is distributed in a vast, flat sheet that stretches for tens of millions of light-years and continues beyond the boundaries of the simulation.

Because nearby galaxies are embedded in this flattened sheet of dark matter, any gravitational pull from our Local Group is counteracted by the gravitational pull from the more distant mass in the sheet, drawing them away from us.

"If the mass were distributed approximately spherically around the Local Group, rather than being flat, then the external galaxies would be moving away from us slower than predicted by Hubble's law for the cosmic expansion, because they would be slowed down by the gravitational pull of the Milky Way and Andromeda," White told Live Science. "Instead, the flattened distribution of the surrounding matter pulls these galaxies outwards in a way which almost exactly compensates for the inward pull of the [Milky Way] and [Andromeda]."

Equally important, the regions above and below the sheet are devoid of galaxies. Such sparse regions occur throughout the cosmos, and the deep Local Voids around our Local Group formed in areas where the initial density of the universe was a bit lower than average.

"As a result these regions expanded faster than average, and their matter was 'pushed' outwards," White said via email. "By the present day these low-density regions fill most of space and gravitational effects have concentrated most of their material into the 'walls' that separate them."

Reconciling experiments, observations and models

The location of the voids is essential. These sparse regions are where any existing structures would fall toward the Local Group; any galaxies there would indeed be moving toward us. So we don't see any other objects careening toward the Milky Way, as Andromeda is doing, because there simply aren't any galaxies there to do so.

Overall, when accounting for the vast sheet of mass, the simulations accurately modeled the distribution of nearby galaxies and the voids, thereby reconciling experimental results with astronomical observations of galactic motions as well as with the leading model of cosmology, known as lambda cold dark matter.

"We are exploring all possible local configurations of the early universe that ultimately could lead to the Local Group," lead study author Ewoud Wempe, a cosmologist at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, said in a different statement. "It is great that we now have a model that is consistent with the current cosmological model on the one hand, and with the dynamics of our local environment on the other."

Interestingly, the researchers report that high-latitude galaxies farther out in the cosmos have been observed to be falling toward the flat sheet of matter at several hundred kilometers per hour. Finding additional structures infalling from the directions of the voids could lend further support to the results of this study.

Wempe, E., White, S. D. M., Helmi, A., Lavaux, G., & Jasche, J. (2026). The mass distribution in and around the Local Group. Nature Astronomy. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02770-w

Ivan is a long-time writer who loves learning about technology, history, culture, and just about every major “ology” from “anthro” to “zoo.” Ivan also dabbles in internet comedy, marketing materials, and industry insight articles. An exercise science major, when Ivan isn’t staring at a book or screen he’s probably out in nature or lifting progressively heftier things off the ground. Ivan was born in sunny Romania and now resides in even-sunnier California.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus