Our leading theory of dark matter may be wrong, huge new gravity study hints

New research using a space-time phenomenon predicted by Einstein presents evidence that the invisible backbone of the universe may be much "fuzzier" than we realized.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Physicists' top theory about the nature of the universe may be wrong, a new study of strangely warped light suggests.

The new research looked into three leading theories of dark matter, the invisible stuff that makes up most of the universe and provides structure to most galaxies, though we still don't know exactly what it is.

For decades, cold dark matter (CDM) has been our leading theory for the universe's invisible scaffolding. It's a neat idea: tiny, slow-moving particles that interact only through gravity. But CDM has its problems. It struggles with explaining galactic anomalies and with describing the strange rotation curves of dwarf galaxies, for example.

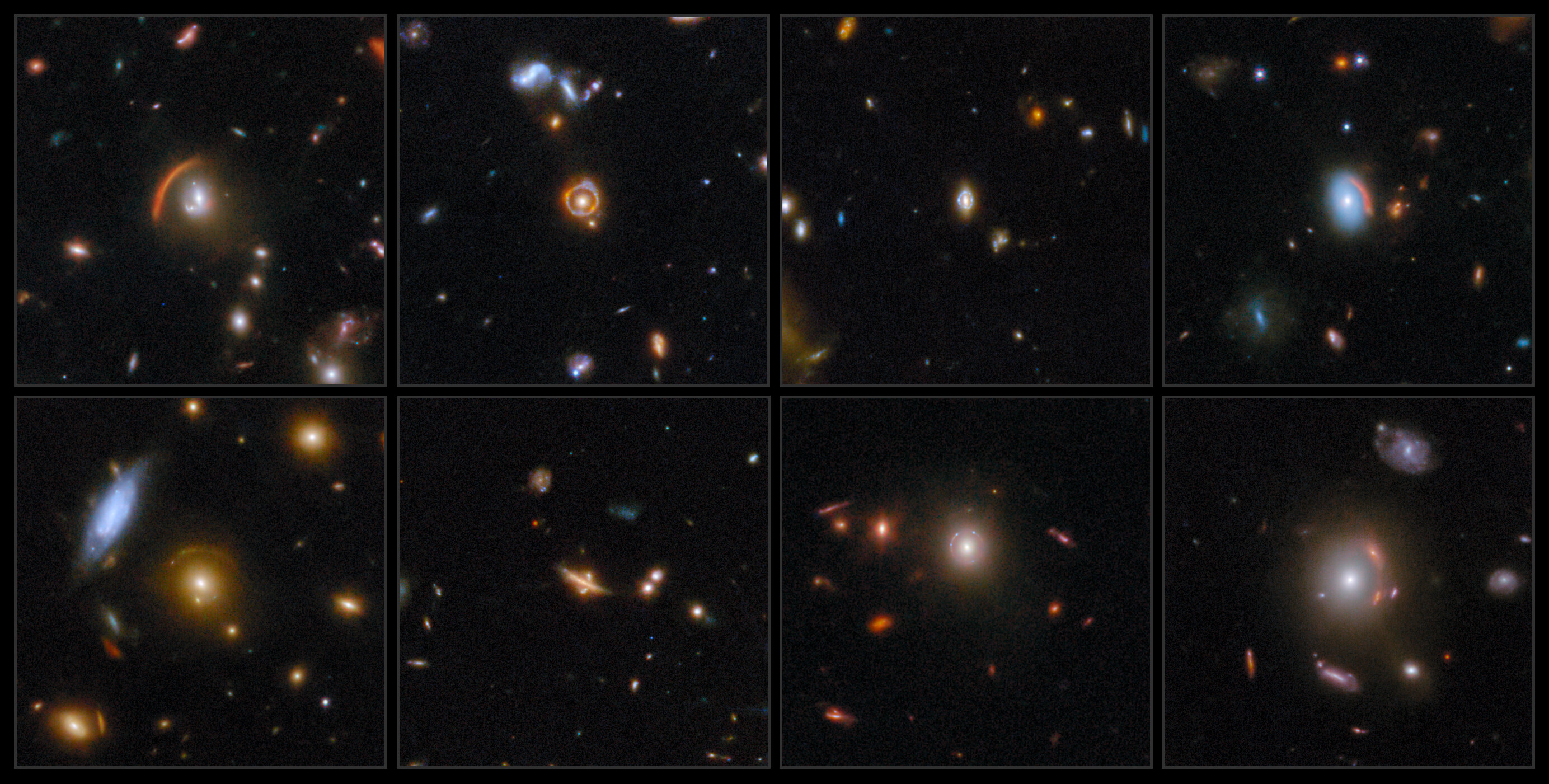

Article continues belowTo further test the nature of dark matter, scientists observe bent starlight from distant galaxies — a process called gravitational lensing — to find critical clues about their hidden architecture. And a new paper published Jan. 23 to the preprint database arXiv turned up something fascinating: This deep lensing analysis decisively disfavors smooth dark matter lens models and strongly prefers fuzzy dark matter (FDM) over both the standard CDM and the more exotic self-interacting dark matter model, which proposes that dark matter slightly sticks to itself.

If it can be bolstered by more evidence, this discovery reveals a fuzzier, more quantum-like reality that underpins everything we know.

Flavors of darkness

Astronomers often talk about different dark matter "flavors," with three major theories topping the menu.

In CDM — the leading theory — dark matter acts like a vast, invisible cosmic scaffolding. It's made of tiny, slow-moving particles. They clump together easily, forming large invisible structures, or "halos," and countless smaller clumps within them. These smaller clumps are subhalos, and they act as gravitational anchors for galaxies.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Self-interacting dark matter, meanwhile, suggests those invisible sand grains of CDM have a slight stickiness or friction when they bump into each other. This extra interaction means that within dense clumps, the particles can transfer energy. It makes the centers of the clumps smoother. It can also cause them to collapse differently.

The final, a la carte model of the universe is fuzzy dark matter. According to this theory, instead of being made of distinct particles, dark matter could be a quantum fog or soup made of incredibly tiny, superlight waves. Because of their wave nature, they can't form extremely sharp, small clumps like CDM. Instead, they create fuzzy, rippling patterns, like gentle waves on a pond. These still bend light, but in a more continuous, less-distinct way than solid clumps would.

A twisted spotlight

The new research, which has not been peer-reviewed yet, really shifts things. Scientists used gravitational lensing data from 11 galaxies — specifically from systems where light bends in particular, sharp ways — to analyze how light bends around massive objects.

The smooth dark matter lens models — the ones we expected from standard CDM — are decisively disfavored by the way light bends in the new dataset. Instead, the data show a strong preference for fuzzy dark matter over both CDM and self-interacting dark matter. This strong preference for fuzzy dark matter persisted even when the researchers made the lens models more complex, and after excluding systems that might be messed up by microlensing.

If fuzzy dark matter is the answer, it completely shifts our understanding of the universe's fundamental building blocks. It would mean dark matter is a quantum wave — that it is not made of discrete, slow-moving particles. Rather, the universe's invisible scaffolding would be more like a vast, cosmic ocean with gentle, rippling currents.

This really changes how astronomers think about galaxy formation and the structure of the cosmos. Our current models, which are based largely on CDM, would need a serious rethink. This also opens up a lot of new questions. Scientists need to figure out how this fuzzy stuff interacts with regular matter. They also need to know what these exotic particles really are.

We started this cosmic detective story trying to understand the universe's true identity, its unseen architecture. For a long time, CDM was the prime suspect — a solid, dependable theory. But the clues, especially from bent starlight, don't quite fit.

Now, with this clever new analysis, we have a compelling piece of evidence suggesting the universe's invisible foundation is far more exotic and quantum than we ever imagined. It's a reminder that the cosmos always has more secrets to reveal.

Hou, S., Xiang, S., Tsai, Y. S., Yang, D., Shu, Y., Li, N., Dong, J., He, Z., Li, G., & Fan, Y. (2026, January 23). Flux-ratio anomalies in cusp quasars reveal dark matter beyond CDM. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.16818

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus