An extra solar system planet once orbited next to Earth — and it may be the reason we have a moon

Earth may have a moon today because a nearby neighbor once crashed into us, a new analysis of Apollo samples and terrestrial rocks reveals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The catastrophic collision that forged the moon, and marked one of the most consequential events in Earth's early history, may have been triggered not by a distant interloper, but by a sibling world that grew up right next door, according to a new study.

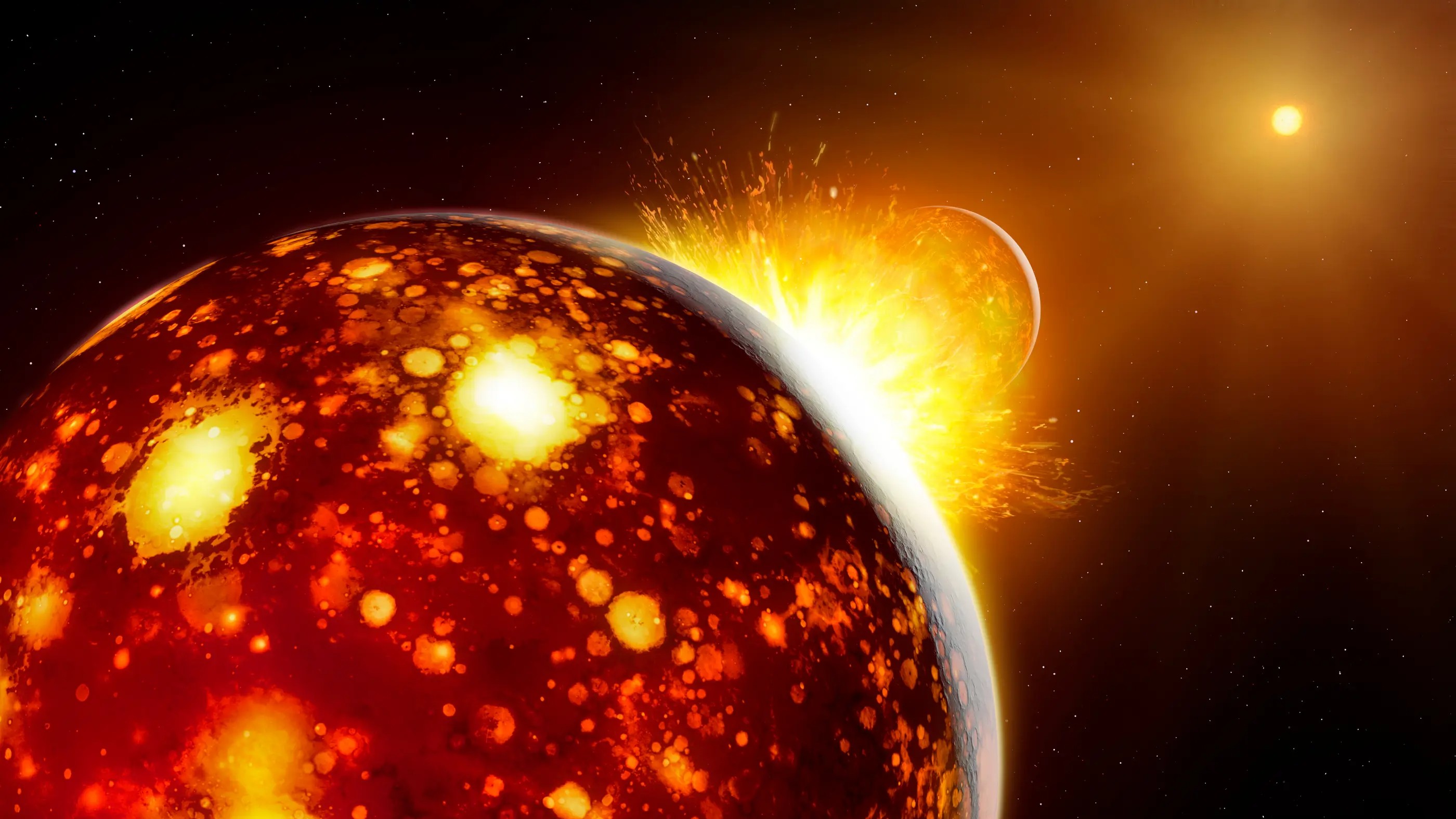

About 4.5 billion years ago, a Mars-size world slammed into the young Earth with such tremendous force that it melted huge swaths of our planet's mantle and blasted a disk of molten debris into orbit. That wreckage eventually clumped together to form the moon we know today. Scientists have long favored this "giant impact" origin story, but where the long-lost world, nicknamed Theia, came from and what it was made of remain a mystery.

But the new analysis of moon samples from Apollo missions, terrestrial rocks and meteorites now argues that Theia, much like Earth, was a rocky world that formed in the inner solar system — likely even closer to the sun than our planet.

"Theia and proto-Earth come from a similar region of the inner solar system," Timo Hopp, a geoscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, who led the research, told Live Science.

The findings, detailed in a paper published Nov. 20 in the journal Science, reinforce the classical picture of how rocky planets assembled billions of years ago, Hopp said.

"Our results do not predict a new twist in the mechanism," Hopp said. Instead, they "are in very good agreement from what we expect from the classical theory of terrestrial planet formation."

Violent youth of the planets

In the turbulent first 100 million years after the sun formed, the inner solar system was crowded with dozens to hundreds of planetary embryos — moon- to Mars-size worlds that frequently collided, merged or were kicked into new orbits by the gravitational chaos of early planet formation, as well as by Jupiter's immense pull.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Theia was one of 10-100s of planetary embryos from which our planets formed," said Hopp. But lunar samples from the Apollo missions have shown that Earth and moon are nearly chemically identical, a similarity that scientists say has made pinpointing Theia's birthplace extremely difficult.

To investigate, Hopp and his colleagues searched for minuscule chemical clues left behind from the impact in Earth's mantle — traces of elements such as iron and molybdenum that should have sunk into Earth's core if they had been present early in the planet's formation. Their survival in mantle rocks today suggests these elements arrived later, likely delivered by Theia during the giant impact, and therefore carry valuable information about the lost planet's composition, the researchers say.

Clues from the moon

The researchers analyzed six lunar samples from the Apollo 12 and 17 missions alongside 15 terrestrial rocks that included specimens from Hawaii's Kīlauea volcano, as well as meteorites recovered from Antarctica and curated in major museum collections.

The team focused on extremely subtle differences in iron isotopes (different versions of elements), which recent research shows can pinpoint where material formed relative to the sun. They combined these iron measurements with isotopic signatures of molybdenum and zirconium, then compared the results with known meteorite compositions to deduce which kinds of planetary "building blocks" could have formed Theia.

Across hundreds of modeled scenarios, from small impactors to bodies nearly half the mass of Earth, the only configuration that successfully reproduced the chemistry of Earth and the moon was the one in which Theia formed in the inner solar system, the study reports. Theia was likely a rocky, metal-cored world containing roughly 5 to 10% of Earth's mass, the team notes.

The models also reveal that both proto-Earth and Theia contain material from an "unsampled" inner-solar-system reservoir, a type of matter absent from all known meteorite collections. This mysterious component likely formed extremely close to the sun, in a region where early material was either swept up by Mercury, Venus, Earth and Theia — or never survived as free-floating bodies capable of becoming meteorites.

"It might be only sample bias," Hopp acknowledged. Samples from Venus or Mercury, he added, may someday reveal larger fractions of this missing material and could ultimately "confirm or reject our conclusion."

While the study clarifies that Earth and Theia were likely local siblings, how the giant impact mixed the two worlds so thoroughly that their chemical identities became nearly indistinguishable remains an open question, Hopp said.

Cracking that mystery may reveal the last missing chapter in the moon's violent origin story — and could be the key to fully understanding how our moon and Earth came to be.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus