Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS may come from the mysterious frontier of the early Milky Way, new study hints

The interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS does not come from our corner of the Milky Way, and may be a time capsule of the early galaxy, new research into its trajectory hints.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers may be closing in on the age and origin of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS as it barrels toward the center of our solar system.

A new study that models the last 4 million years of the comet's journey through the Milky Way hints that the interstellar visitor came from far, far away — potentially originating from the wild frontier where the galaxy's oldest and youngest stars meet. If that's the case, the comet may be a relic of the early galaxy, dating billions of years older than Earth's sun.

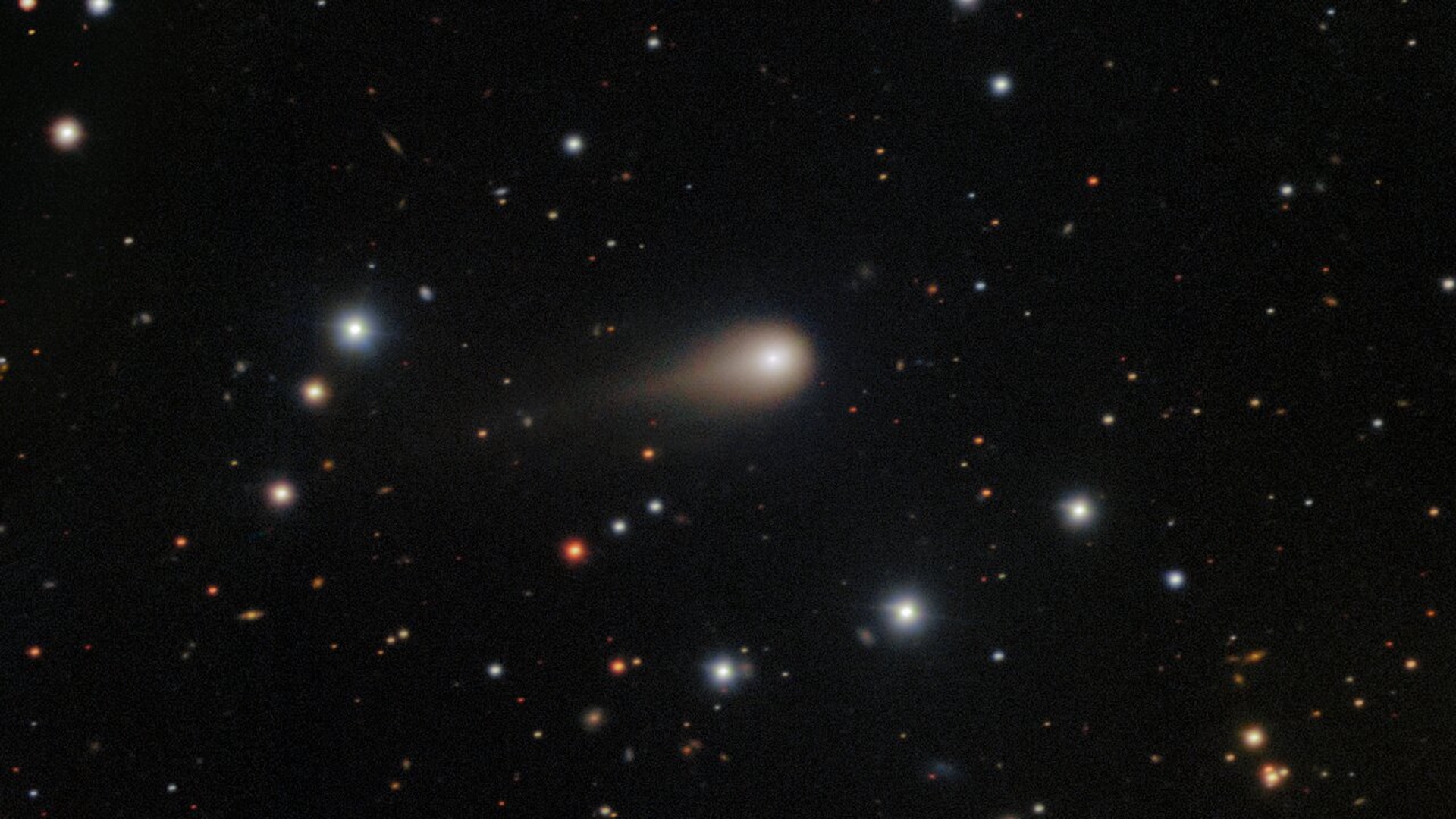

First spotted in late June and confirmed by NASA in early July, 3I/ATLAS is a peculiar comet whose staggering speed and odd trajectory indicate that it came from a star system beyond our own. It is only the third interstellar object ever detected — after 1I/'Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov — and appears to be the largest so far, with recent estimates putting it somewhere between 3 and 7 miles (4.8 to 11.2 kilometers) wide.

Galactic grand tour

This cosmic visitor is currently taking a months-long sightseeing tour through our inner solar system, completing a close approach to Mars on Friday (Oct. 3) and poised to make its closest swoop past the sun on Oct. 30, according to NASA. After that, it will head out toward interstellar space again, passing Jupiter in March of 2026 before finally disappearing from view. The comet poses no threat to Earth.

While 3I/ATLAS's immediate trajectory is easy to predict, figuring out where it came from is much harder.

Traveling at about 130,000 miles per hour (210,000 kmh), a record for interstellar objects, the renegade ice ball has been picking up speed for millions, if not billions, of years. That leaves it vulnerable to the gravitational tugs of an untold number of Milky Way stars. Just as NASA uses the gravitational influence of our solar system's planets to slingshot spacecraft into deeper orbits, 3I/ATLAS could easily have been knocked off its original trajectory by the gravity of massive stars intervening in its path.

Now, new research published to the preprint server arXiv makes the best effort yet to pin down the comet's origins by looking at which nearby stars, if any, may have influenced its orbit.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

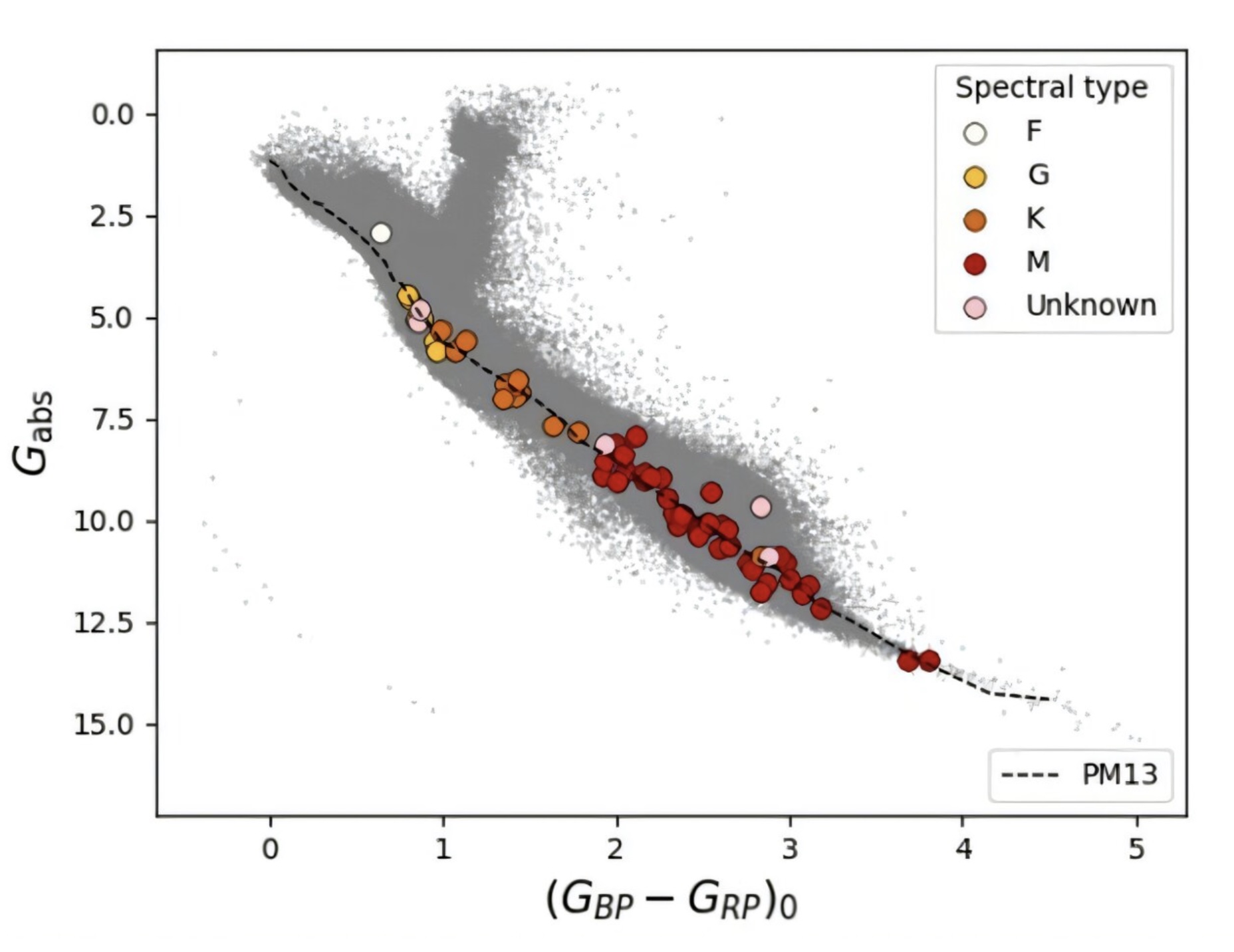

Using data from the European Space Agency's now-retired Gaia space telescope, the study authors traced the comet's trajectory back in time 4.27 million years and identified 62 nearby stars that the interstellar object likely encountered along the way. Using Gaia's high-definition data on the stars' motions, velocities and sizes, the study authors concluded that none of them have significantly altered the comet's orbit — hinting that it did not originate anywhere near us.

"We have found that none of the stars in the solar neighborhood can explain the trajectory and high velocity of 3I/ATLAS," lead study author Xabier Pérez-Couto, an astrophysics postgraduate student at Spain's Universidade da Coruña, told Live Science in an email. Only one nearby star, measuring about 70% the mass of the sun, appears to have impacted the comet's trajectory at all, but it was only by a negligible amount, the researchers added in their paper.

This led the team to postulate that "3I/ATLAS is a very old object, that has been traveling for [billions of years], and that its origin belongs to the border of the thin disk," Pérez-Couto said.

Object from the wild frontier?

What's so special about that? Spiral galaxies like the Milky Way divide their stars between a thin disk and a thick disk. Slicing through the central bulge of our galaxy, the younger and smaller thin disk is thought to contain the vast majority of the Milky Way's stars and star-forming gases — most of which are rich in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, picked up from the older generations of stars that lived and died before them. By contrast the broader thick disk, wrapped around the borders of the thin disk, has long ceased its star formation. It contains a smaller — but much older — sampling of stars that are poor in heavy metals, according to Swinburne University of Technology in Australia.

If comet 3I/ATLAS did indeed originate from the border of these two disks, it could mean the object is incredibly old — potentially 10 billion years old, making it more than double the age of our roughly 4 billion-year-old sun. According to Pérez-Couto, the comet was likely "ejected from the primordial disk of an early formed planetary system," potentially making it a valuable time capsule of the ancient Milky Way.

However, the new study acknowledges the limitations of its approach: by looking at nearby stars, the analysis only accounts for a few million years of the comet's long history, making its exact origin still highly uncertain. As 3I/ATLAS continues to zoom through the solar system, scientific instruments on Earth and Mars, as well as those in orbit around Jupiter, will soon have the chance to study it in much greater detail. Unraveling the interstellar object's composition will provide essential clues to its cosmic birthplace — and potentially open a precious window into our galaxy's past.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus