Dozens of mysterious blobs discovered inside Mars may be the remnants of 'failed planets'

"Marsquake" data collected by NASA's InSight lander have revealed dozens of mysterious blobs within the Red Planet's mantle. The structures may have been left by powerful impacts up to 4.5 billion years ago.

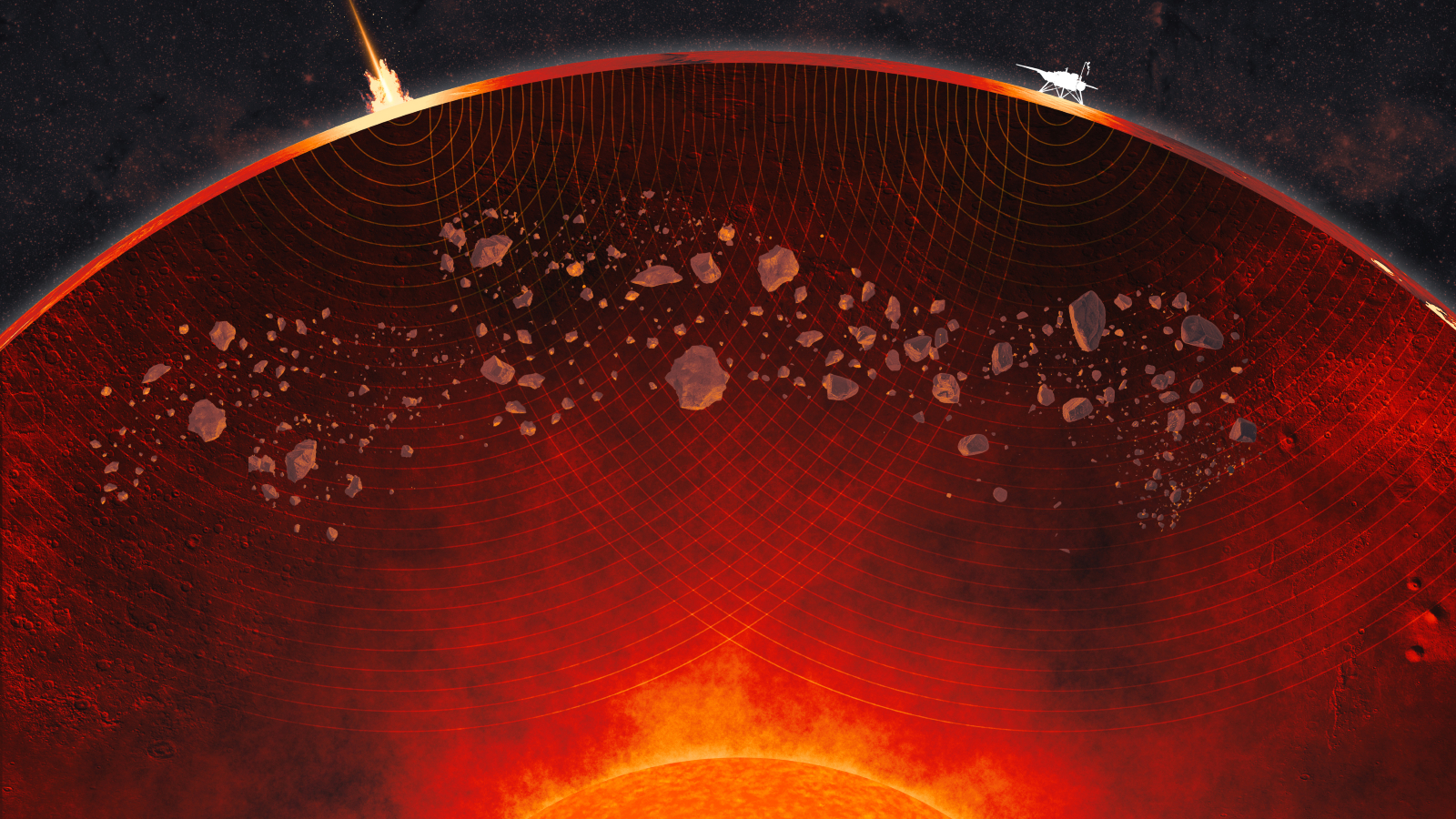

Giant impact structures, including the potential remains of ancient "protoplanets," may be lurking deep beneath the surface of Mars, new research hints. The mysterious lumps, which have been perfectly preserved within the Red Planet's immobile innards for billions of years, may date back to the beginning of the solar system.

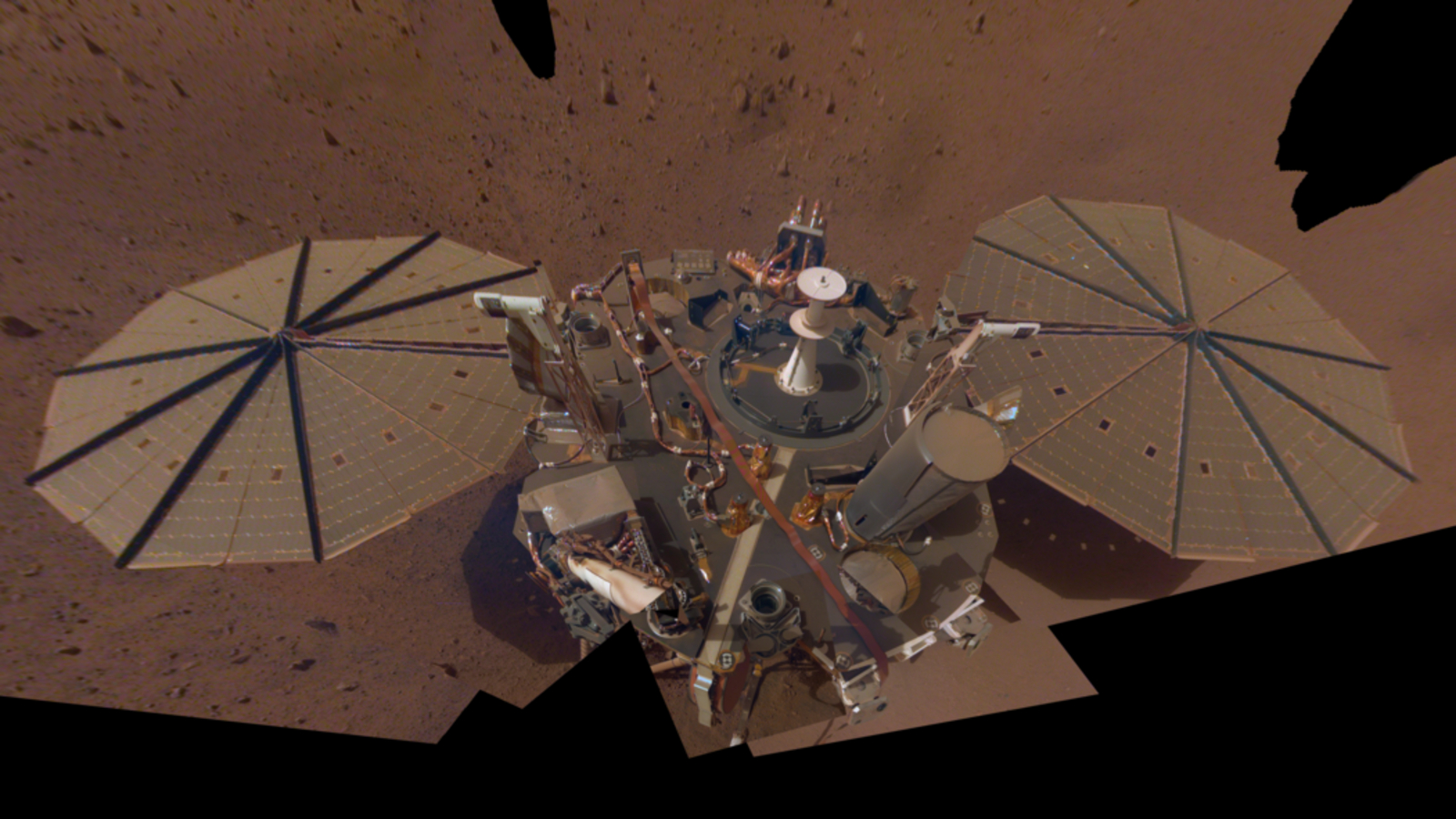

In a new study, published Aug. 28 in the journal Science, researchers analyzed "Marsquake" data collected by NASA's InSight lander, which monitored tremors beneath the Martian surface from 2018 until 2022, when it met an untimely demise from dust blocking its solar panels. By looking at how these Marsquakes vibrated through the Red Planet's unmoving mantle, the team discovered several never-before-seen blobs that were much denser than the surrounding material.

The researchers have identified dozens of potential structures, measuring up to 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) across, at various depths within Mars' mantle, which is made of 960 miles (1,550 km) of solid rock that can reach temperatures as high as 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit (1,500 degrees Celsius).

"We've never seen the inside of a planet in such fine detail and clarity before," study lead author Constantinos Charalambous, a planetary scientist at Imperial College London, said in a NASA statement. "What we're seeing is a mantle studded with ancient fragments."

Based on the hidden objects' size and depth, the researchers think the structures were made when objects slammed into Mars up to 4.5 billion years ago, during the early days of the solar system. Some of the objects were likely protoplanets — giant rocks that were capable of growing into full-size planets if they had remained undisturbed, the researchers wrote.

Related: 32 things on Mars that look like they shouldn't be there

The researchers first noticed the buried structures when they found that some of the Marsquake signals took longer to pass through parts of the mantle than others. By tracing back these signals, they identified regions with higher densities than the surrounding rock, suggesting that those sections did not originate there.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mars is a single-plate planet, meaning that its crust remains fully intact, unlike Earth's, which is divided into tectonic plates. As pieces of Earth's crust subduct through plate boundaries, they sink into the mantle, which causes the molten rock within our planet to rise and fall via convection. But on Mars, this does not happen, which means its mantle is fixed in place and does not fully melt.

The newly discovered blobs are further proof that Mars' interior is much less active than Earth's.

"Their survival to this day tells us Mars' mantle has evolved sluggishly over billions of years," Charalambous said. "On Earth, features like these may well have been largely erased."

Because Mars has no tectonic activity, Marsquakes are instead triggered by landslides, cracking rocks or meteoroid impacts, which frequently pepper the planet's surface. These tremors have also been used to detect other hidden objects beneath the Red Planet's surface, including a giant underground ocean discovered using InSight data last year.

In total, InSight captured data on 1,319 Marsquakes during its roughly four-year-long mission. However, scientists were still surprised that they could map the planet's insides in such great detail.

"We knew Mars was a time capsule bearing records of its early formation, but we didn't anticipate just how clearly we'd be able to see with InSight," study co-author Tom Pike, a space exploration engineer at Imperial College London, said in the statement.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus