Einstein was right: Time ticks faster on Mars, posing new challenges for future missions

Clocks on Mars tick faster by about 477 microseconds each Earth day, a new study suggests. This difference is significantly more than that for our moon, posing potential challenges for future crewed missions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have found that time moves slightly faster on the Red Planet than it does on Earth. Clocks on Mars tick, on average, 0.477 milliseconds (477 microseconds) faster over 24 hours when measured from Earth compared with time recorded on our planet, a new study finds. Knowing this difference may help in establishing an "internet" across the solar system.

Over the next few decades, humanity's presence in the solar system is set to boom, with missions like those in NASA's Artemis program expected to pave the way for permanent settlements on the moon and beyond. Developing a standard clock for each cosmic locale would help astronauts navigate these worlds while coordinating communications with Earth.

But there's a catch: Time doesn't run at the same pace everywhere. Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity shows that time in a given area depends on how strong the gravity is there. Clocks in areas of high gravity tick more slowly than those where gravity is weaker, which is why people residing atop mountains age a fraction of a millisecond faster than sea-level dwellers. (Time appears to move faster at high altitudes, where Earth's gravitational tug is reduced.)

Article continues belowAdditionally, time on a planet depends on its velocity around its parent star; the faster the orbital rate, the faster the passage of time.

Time keeps on slippin'

Together, velocity and gravity cause time on different solar system bodies to tick at different rates when measured from Earth. A 2024 study calculated that clocks on the moon would run an average of 56 microseconds (millionths of a second) faster than Earth-based ones. Having established this, the researchers — Neil Ashby and Bijunath Patla, both physicists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado — turned their attention to Mars.

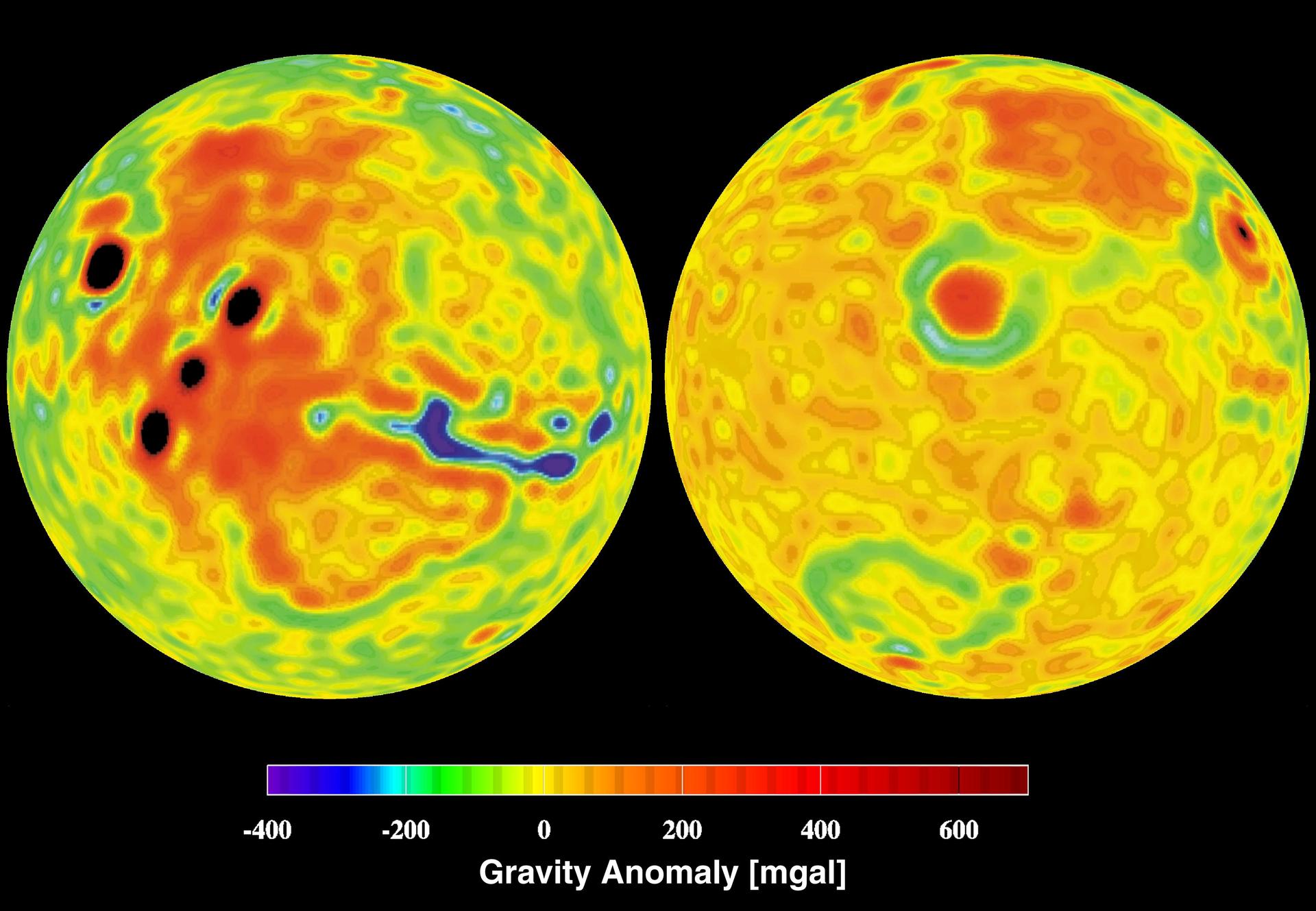

First, they chose a reference level on Mars — an equivalent to Earth's sea level called the areoid. Then, they used physics-based formulas to calculate how, at the areoid, Mars' and Earth's gravities and velocities would influence Martian time. Although Mars' slower orbital speed relative to Earth slows down Mars-based clocks, the planet's weaker surface gravity — five times lesser at the areoid than Earth's sea-level gravity — speeds them up much more.

But this analysis neglected the orbits' shapes. Mars' orbit is more egg-shaped than Earth's, having been contorted by the gravitational tugs of Earth and its moon. (Mars' moons, Deimos and Phobos, have a negligible impact, Patla told Live Science in an email, because of their puny size. They're just a few miles wide, compared with 2,159 miles, or 3,475 kilometers, for Earth's moon.) So, Ashby and Patla factored Mars' orbital shape, the sun's gravity and Earth moon's gravity into their equations.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Setting clocks on Mars

The analysis showed that Martian clocks tick faster, when measured from Earth, than Earth-based ones by an average of 477 microseconds per Earth day. Strikingly, though, this value varies daily by 226 microseconds (about half the offset's value itself) over a Martian year. The variation stems from the egg-like shape of Mars’ orbit and changes in the gravitational tugs of its celestial neighbors as they approach and twirl away from Mars.

Additionally, the researchers found that the clocks change by an extra 40 microseconds over seven of Mars' synodic periods, with a synodic period being how long the planet takes to reappear in the same position of the sky.

"The fluctuation and the Earth-Mars planetary dance (synodic period) variation was a surprise," Patla said, because their magnitudes were larger than he expected.

The findings, published Dec. 1 in The Astronomical Journal, will help scientists synchronize time across the solar system, allowing them to establish rapid communications channels in an interplanetary internet in the distant future, although the large fluctuations will complicate this effort, Patla said. He added that the study "provides a baseline for future tests of general relativity and fundamental physics, which explore the nature of spacetime."

But the calculations were still inaccurate by about 100 nanoseconds (0.1 microseconds) per day over long timescales, because tiny shifts in the planets' movements weren't factored in. Although this imprecision is minuscule, it would mean resetting Martian clocks every 100 days.

The study also didn't account for factors like how the planets' orbits precess, or gradually wobble, and the effects of Earth's and Mars' gravitational quadrupole moments, which is a measure of how their mass is arranged within their structures. Taken together, these limitations may make it more challenging to obtain more precise time calculations, the researchers said.

Deepa Jain is a freelance science writer from Bengaluru, India. Her educational background consists of a master's degree in biology from the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, and an almost-completed bachelor's degree in archaeology from the University of Leicester, UK. She enjoys writing about astronomy, the natural world and archaeology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus