Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

A species of moss survived for 9 months on the outside of the International Space Station, new research reveals — and 80% of the samples kept reproducing when returned to Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

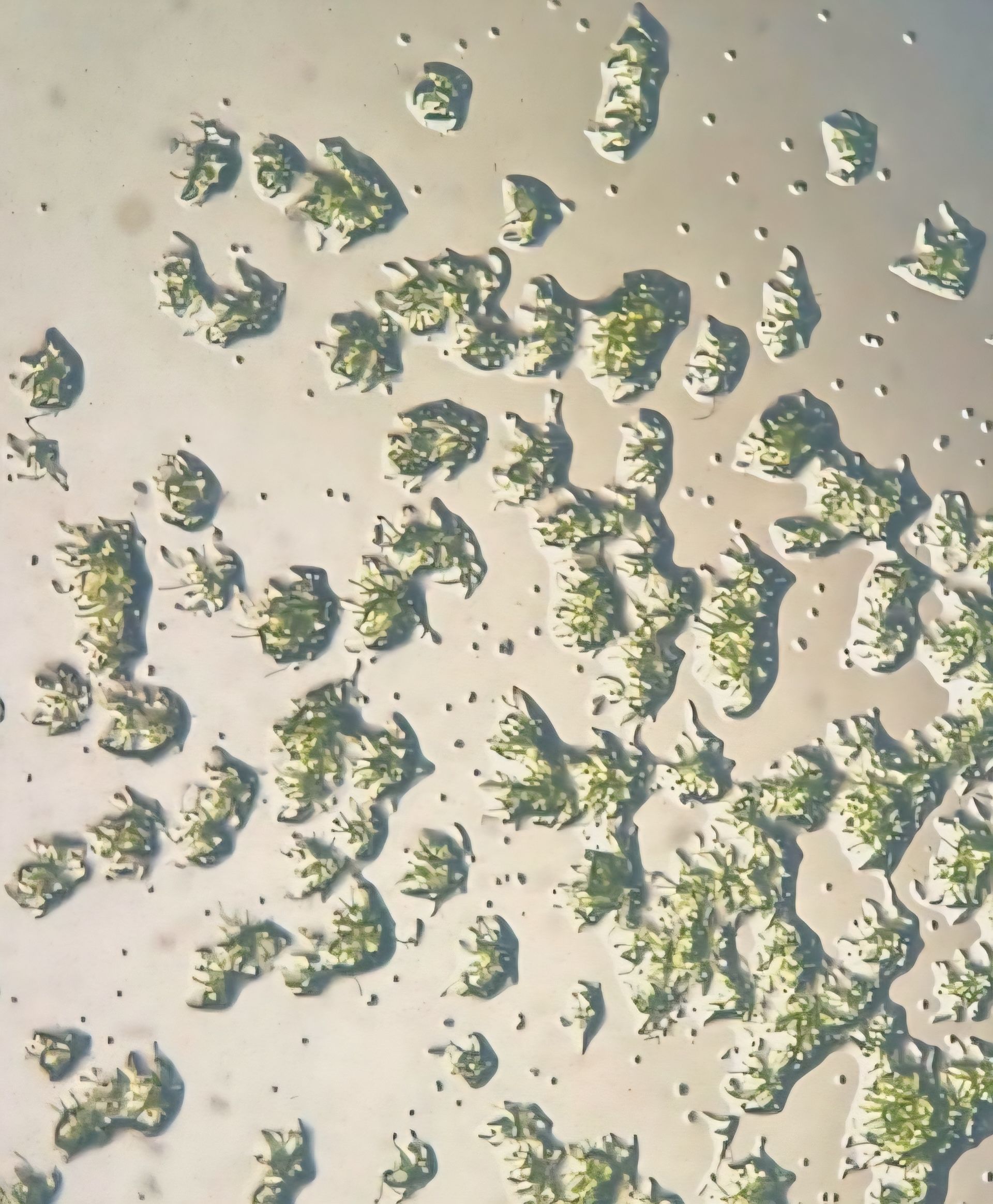

Moss spores have survived a prolonged trip to space, scientists reveal. The spores spent nine months on the outside of the International Space Station (ISS) before returning to our planet, and over 80% of the spores were still able to reproduce when they arrived back on Earth.

The discovery improves our understanding of how plant species survive in extreme conditions, the researchers wrote in their findings, published Thursday (Nov. 20) in the journal iScience.

Moss thrives in some of the most extreme environments on Earth, from the cold peaks of the Himalayas to the dry, scorched sands of Death Valley. Moss's resilience to adverse conditions makes it an ideal candidate for surviving in the harsh environment of outer space, where extreme temperature fluctuations, altered gravity, and high radiation exposure push life-forms to their limits.

Previous experiments have explored how plants might cope in space, but so far, they have focused on larger organisms such as bacteria or plant crops. Now, researchers have shown that samples of the moss Physcomitrium patens (P. Patens) can not only survive but thrive in space.

First, the researchers tested three cell types of P. patens from various stages in the moss's reproductive cycle. They found that sporophytes — cell structures that encase spores — showed the greatest stress tolerance when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light, freezing and heat.

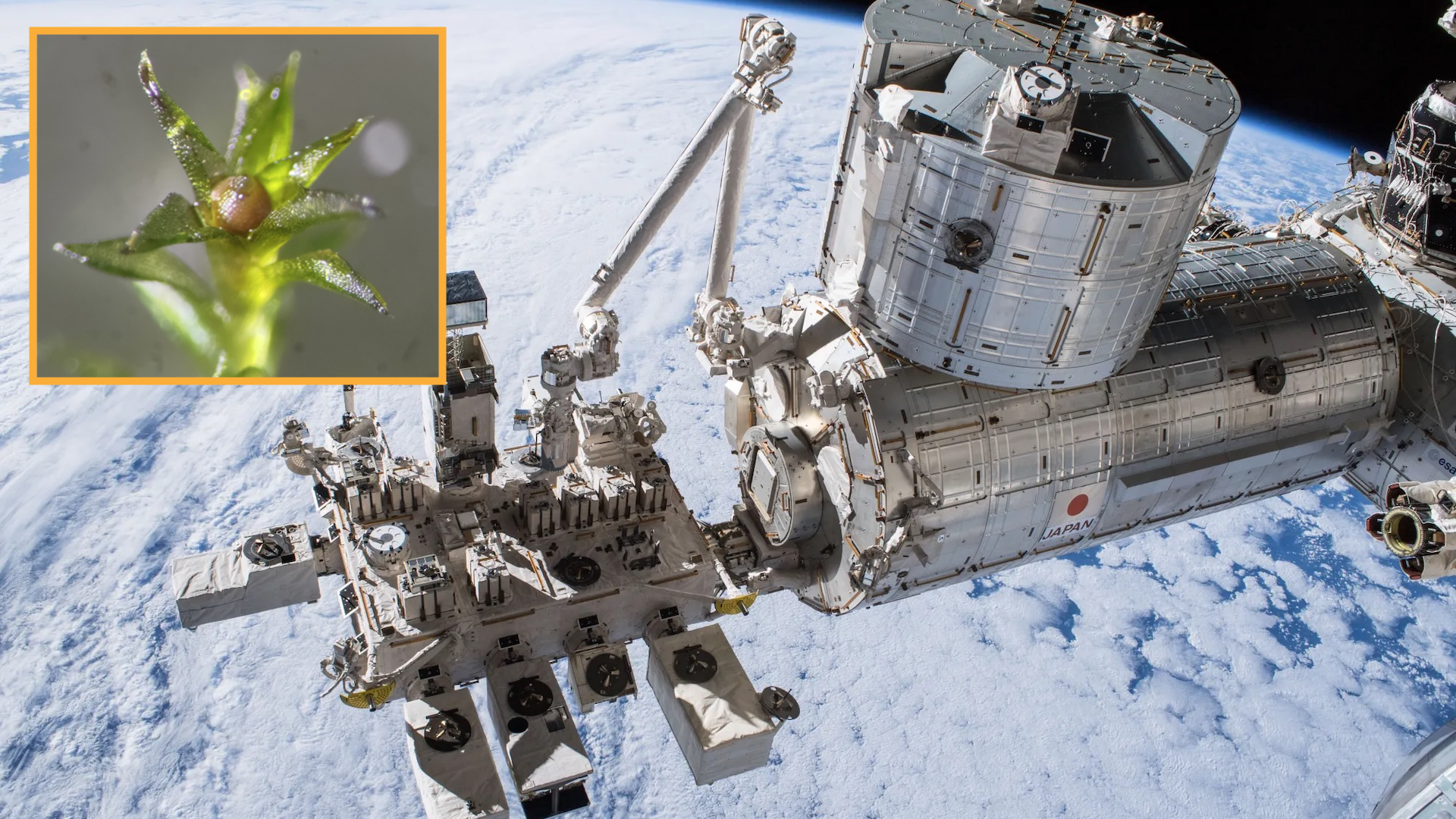

Sporophyte samples were then placed outside of the ISS in a special exposure facility attached to Japan’s Kibo module, where the samples lived for around nine months in 2022. After this time, the samples were returned to Earth.

"Surprisingly, over 80% of the spores survived and many germinated normally," study lead author Tomomichi Fujita, a professor of plant biology at Hokkaido University in Japan, told Live Science in an email. From this study, Fujita and his team developed a model that suggests the moss spores could actually survive for up to 5,600 days in space, or around 15 years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Back on Earth, the team found that most of the conditions — including the vacuum of space, microgravity and extreme temperature fluctuations — had a limited impact on the moss spores. However, samples that were exposed to light, particularly high-energy wavelengths of UV light, fared less well. Levels of pigments used by the moss for photosynthesis, such as chlorophyll a, were significantly reduced as a result of light damage, which affected later moss growth.

Even though some moss samples faced damage from the conditions of outer space, P. patens still fared much better than other plant species that have been previously tested under similar conditions. Fujita thinks the protective, spongy casing surrounding the spores may help defend against UV light and dehydration.

"This protective role may have evolved early in land plant history to help mosses colonize terrestrial habitats," he said.

While this may seem like an exercise in testing the limits of a single species, the "spores' success in space could offer a biological stepping stone for building ecosystems beyond our planet," Fujita said. In the future, he hopes to test other species and better understand how these resilient cells survive such stressful conditions.

Mason Wakley is a freelance science journalist from the UK, most interested in chemistry, materials and environmental science. He was a 2025 Chemistry World intern. Mason has a masters in chemistry from the University of Oxford.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus