Pumas in Patagonia started feasting on penguins — but now they're behaving strangely, a new study finds

Pumas in Patagonia, Argentina are eating penguins in a national park — and it's changing how the big cats are interacting with each other.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Pumas in Patagonia are preying on penguins — and it's changing how the big cats interact with each other.

The pumas in question reestablished themselves in an Argentinian national park that housed a penguin breeding colony — and the cats promptly began eating the birds. Now, it turns out the normally solitary cats that eat the penguins are tolerating each other more often than expected, new research published Wednesday (Dec. 17) in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B reports.

The findings suggest that reintroductions like these can have surprising knock-on effects.

Article continues below"Restoring wildlife in today's changed landscapes doesn't simply rewind ecosystems to the past," said study co-author Mitchell Serota, an ecologist at Duke Farms in New Jersey. "It can create entirely new interactions that reshape animal behavior and populations in unexpected ways."

Sheep ranchers in Patagonia forced pumas out of the region in the 20th century. After Monte Leon National Park was established in 2004, pumas have started making their way back. But in the pumas' absence, other species had adapted to the reduced hunting pressure. For example, a group of Magellanic penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus), usually confined to offshore islands, established a mainland breeding colony consisting of some 40,000 breeding pairs.

Shortly after the park was established, researchers started noticing penguin remains in puma scat. The pumas were taking advantage of the changed ecosystem.

"We thought it was just a couple individuals that were doing this," said Serota, who conducted the research while he was a doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley. "But when we got there … we noticed a ton of puma detections near the penguin colony."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

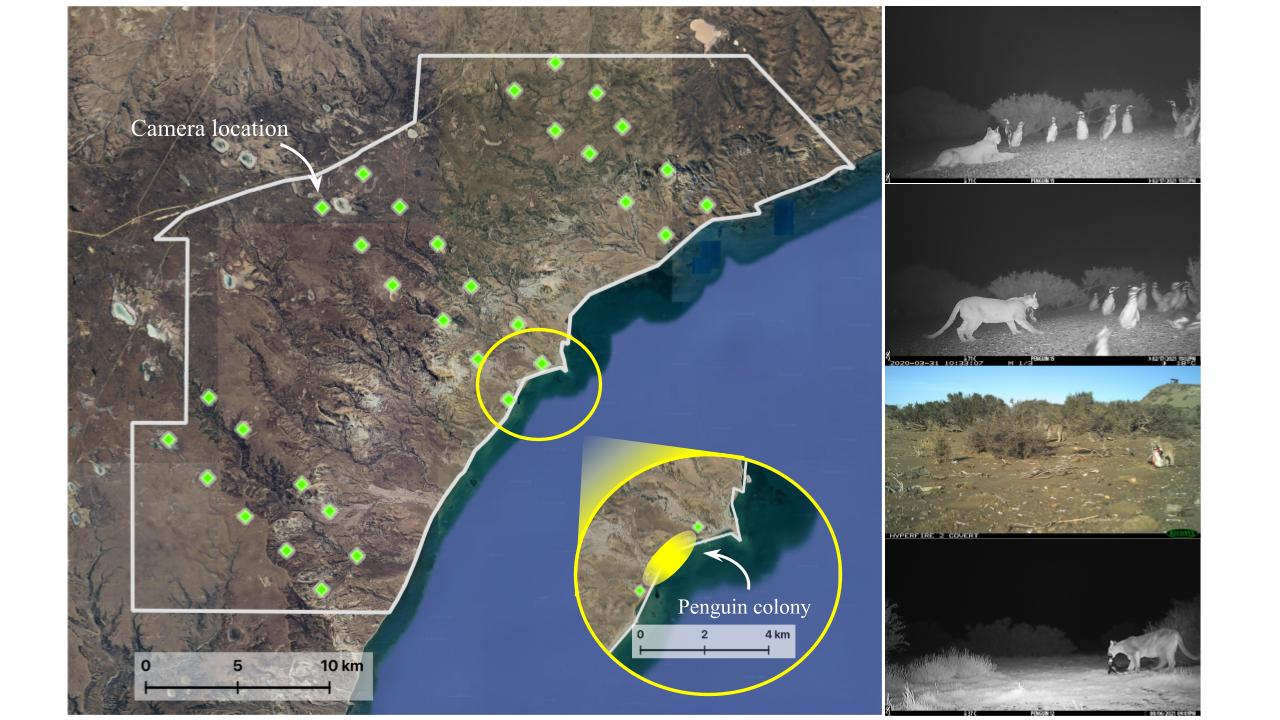

In the new study, researchers used cameras to estimate how many pumas lived near the penguin breeding colony, a 1.2 mile (2 kilometers) stretch of beach inside the national park. They also tracked 14 individual pumas with GPS collars and investigated penguin kill sites across several field seasons between 2019 and 2023. Nine of the pumas they tracked hunted penguins, while five did not.

Pumas that ate penguins had bigger variation in their ranges from season to season, the study found. The penguin-eating cats stuck close to the penguin colony when the birds were in the national park during breeding season. But they ranged about twice as far when the birds migrated offshore during the summer.

Penguin-eating pumas also interacted with each other more often than pumas who relied on other prey. The researchers documented 254 encounters between any two of the pumas who both ate penguins, and just four encounters between pumas where neither ate penguins. Most meetings between pumas occurred within 0.6 miles (1 km) of the penguin colony.

Because multiple pumas were using the colony as a food source, this disparity suggests that penguin-eating pumas tolerate other pumas better than those that rely on other prey, likely because they don't have to compete as much for the plentiful food. In fact, the researchers found that the density of pumas within the park was more than twice the highest previously-recorded concentration within Argentina. Usually, adult pumas are solitary and establish large ranges to ensure they have enough prey to feed themselves and their kittens.

Understanding how large carnivores behave when they return to ecosystems impacted by humans "is essential for conservation planning because it allows managers to … design management strategies that are grounded in how ecosystems actually function today, not how we assume they should function based on the past," Juan Ignacio Zanon Martinez, a population ecologist at Argentina's National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) who was not involved in the study, wrote in an email to Live Science.

Knowing how the pumas' behavior affects both the cats and the penguins could aid future conservation efforts in the park.

For example, puma predation might not have a big effect on large breeding colonies, but it could affect the growth of new, smaller colonies. It's a "complex situation for the people who do the management of the area, because you have two native [species] interacting," in a way that's different from before human activities changed the ecosystem, said Javier Ciancio, a biologist at CONICET who was not involved in the new study.

In future work, Serota says the team will investigate how the relationship between pumas and penguins affects pumas' other prey, such as the guanaco (Lama guanicoe), a relative of the llama.

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus