James Webb telescope finds supermassive black hole hidden inside 'Jekyll and Hyde' galaxy

The discovery of a hidden supermassive black hole inside an ancient galaxy suggests that some of our universe's most extreme objects could be invisible unless observed in infrared wavelengths, James Webb telescope observations reveal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has detected a supermassive black hole hiding in an ancient "Jekyll and Hyde" galaxy that changes its appearance depending on how you look at it.

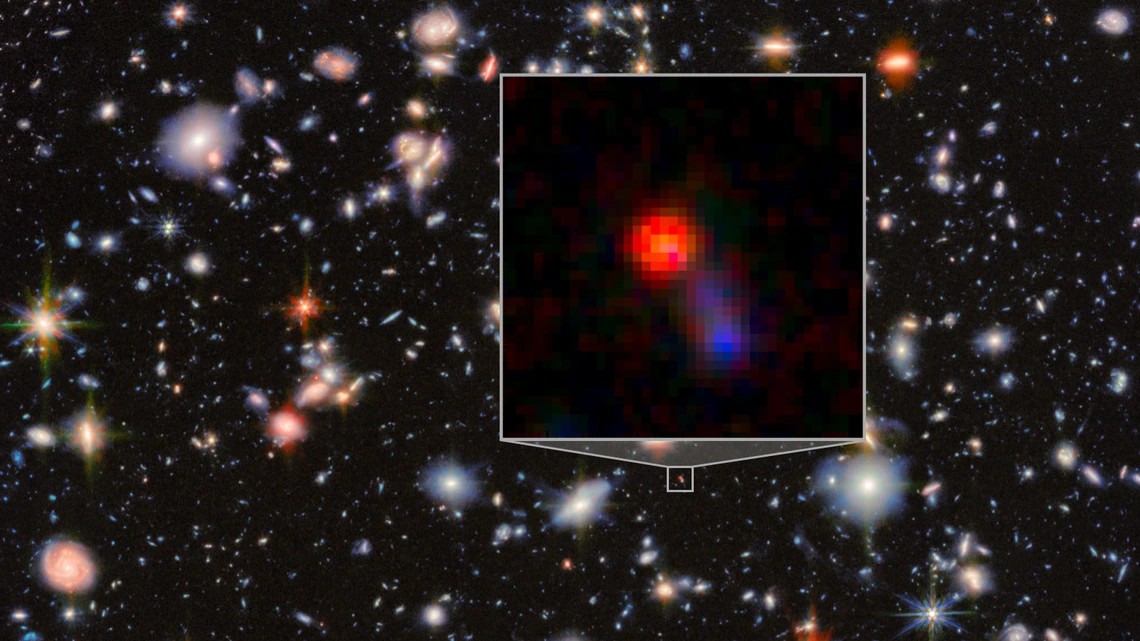

The galaxy, nicknamed Virgil, looked like an ordinary star-forming galaxy when observed in optical wavelengths (the kind of light that human eyes and optical telescopes like Hubble can see). However, when JWST viewed the object in infrared via its Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), a monster black hole became visible in the galaxy's core.

"Virgil has two personalities," George Rieke, an astronomer at the University of Arizona who co-led the discovery, said in a statement released Dec. 10. "The UV and optical show its 'good' side — a typical young galaxy quietly forming stars. But when MIRI data are added, Virgil transforms into the host of a heavily obscured supermassive black hole pouring out immense quantities of energy."

Article continues belowRieke and his colleagues published their findings Nov. 17 in The Astrophysical Journal. The findings suggest that some of our universe's most extreme objects could be invisible unless observed in infrared wavelengths.

Light takes a long time to travel across the galaxy, so when a powerful telescope like JWST observes distant objects, it sees the objects as they appeared in the distant past. Basically, JWST acts like a time machine into the early universe. Virgil appears to JWST as it existed 800 million years after the Big Bang. (For context, the universe is thought to be around 13.8 billion years old.)

The researchers classified Virgil as a little red dot (LRD). This is the name given to mysterious red objects that appear in JWST observations of the distant, early universe, and that astronomers don't fully understand.

LRDs appear in large numbers at around 600 million years after the Big Bang, before rapidly declining at around 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang. Observing galaxies like Virgil should help researchers unravel the mysteries of LRDs, which have been linked to actively feeding supermassive black holes that are heavily obscured by dust.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

JWST's Virgil observations also help researchers better understand how supermassive black holes grew in the early universe. The one at the center of Virgil was a so-called "overmassive" black hole — meaning a massive black hole that shouldn't be able to exist in a host galaxy of that size, according to the statement.

Astronomers used to think that black holes at the centers of galaxies grew at the same rate as their hosts, with the galaxies forming first and growing black holes over time as large quantities of matter coalesced at their centers. However, JWST observations like this one suggest that the opposite might be true — first comes the black hole, then the galaxy around it.

"JWST has shown that our ideas about how supermassive black holes formed were pretty much completely wrong," Rieke said. "It looks like the black holes actually get ahead of the galaxies in a lot of cases. That's the most exciting thing about what we're finding."

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus