We were wrong about how the moon's largest and oldest crater formed — and that's great news for NASA's next lunar landing

A new study has revealed that our understanding of the South Pole-Aitken basin was quite literally back-to-front, meaning astronauts on NASA's future Artemis III mission may be able to collect valuable samples of ancient radioactive material, known as KREEP.

The largest and oldest crater on the moon did not form as we initially suspected, a new study suggests. The findings hint that a specific region of the lunar surface could be more scientifically interesting than we thought — with big implications for NASA's upcoming Artemis missions, which are scheduled to land astronauts within this newly realized area of interest as soon as 2027.

The moon formed around 4.46 billion years ago, when an ancient Mars-size protoplanet, known as Theia, collided with Earth, creating a giant cloud of debris that combined into a large spherical satellite orbiting our planet. For the next 200 million years or so, the lunar surface was covered by a hellish magma ocean, as a result of gravitational squeezing from Earth. But as the moon moved farther away from our planet, the molten rock eventually cooled and crystalized, forming an outer rocky crust that has remained largely unchanged ever since — aside from a near-constant bombardment of space rocks.

Shortly after the moon cooled off, around 4.3 billion years ago, an asteroid more than 10 times wider than the one that wiped out the dinosaurs slammed into what is now the satellite's permanent far side. This birthed the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin, a giant impact crater around 1,550 miles (2,500 kilometers) across and up to 5 miles (8 km) deep. Researchers believe that this extreme impact may have ejected a mix of radioactive material, dubbed "potassium, rare earth elements and phosphorus" or KREEP, that was left over from the past magma ocean. (The chemical symbol for potassium is K, hence the name KREEP.)

KREEP is believed to have formed during the final cooling phase of the moon, when radioactive elements built up in the space between the moon's newly formed mantle and crust. Studying these elements more closely could help shed light on several mysteries surrounding this period of lunar evolution, including why the crust on the moon's far side is thicker than its visible near side.

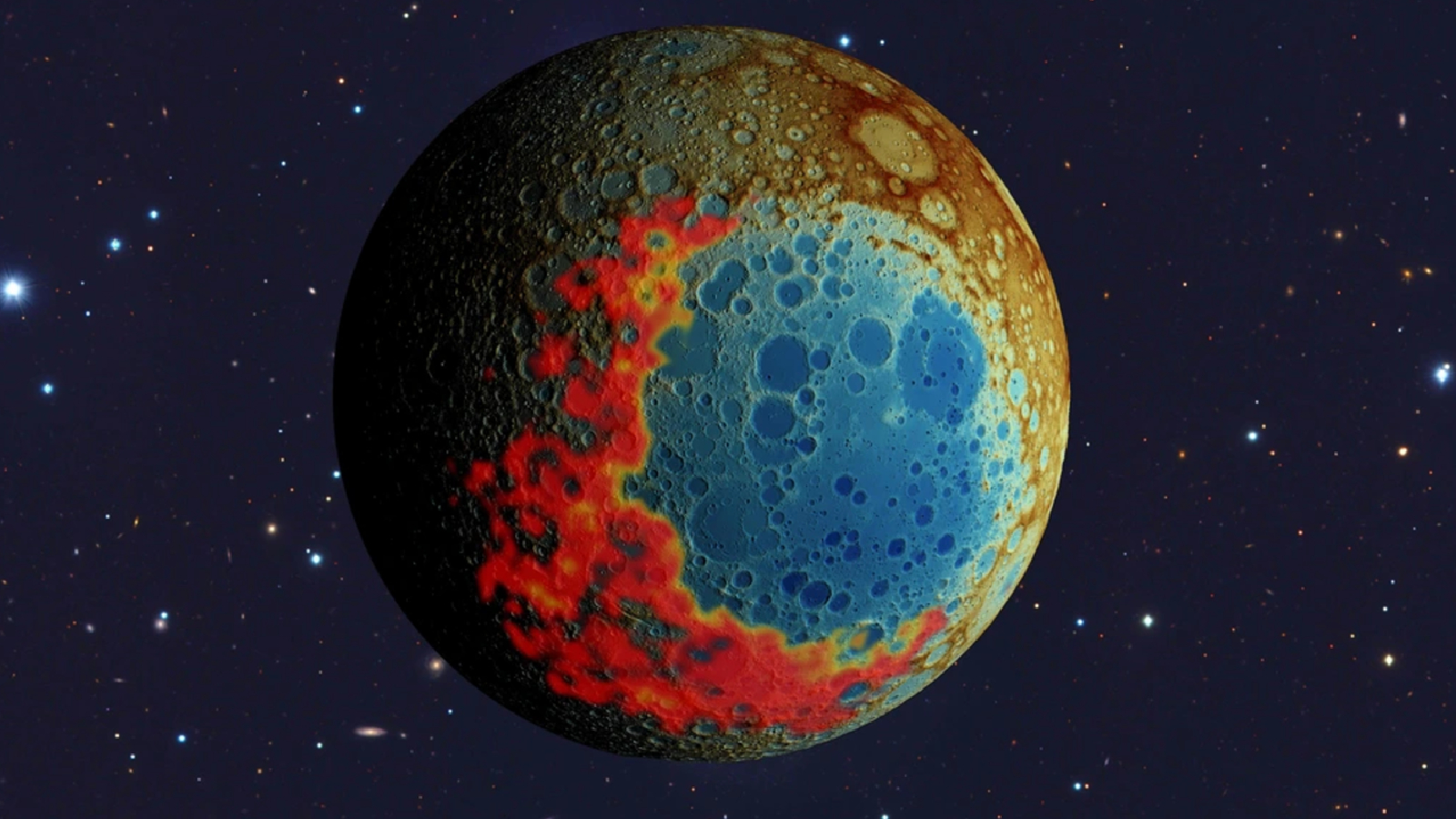

Until now, researchers believed that the SPA basin was formed by an asteroid impacting the moon from the south, which would have splashed a layer of KREEP around the crater's northern rim. However, in a new study, published Oct. 8 in the journal Nature, researchers found that the impact actually occurred from the north, meaning that the resulting KREEP is plastered around the southern edge of the crater — right where the crewed Artemis III mission is scheduled to land.

"This means that the Artemis missions will be landing on the down-range rim of the basin — the best place to study the largest and oldest impact basin on the moon," study lead author Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, said in a statement. This is "where most of the ejecta, material from deep within the moon's interior, should be piled up," he added.

The researchers became suspicious of the SPA basin's true origins when they compared its shape to other impact craters in the solar system, including Mars' Hellas basin and Pluto's Sputnik basin. All three craters have a similar shape, with one rounded end and another more pointed, making them look somewhat like an avocado or teardrop. The pointed tip of these craters likely represents the direction of impact, enabling researchers to guess which way the SPA basin asteroid hit.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These suspicions were confirmed when the team analyzed data from the Lunar Prospector, a NASA spacecraft that orbited the moon from 1998 to 1999 and measured the radioactivity of surface elements. This revealed a high concentration of thorium — a radioactive element and key component of KREEP — around the crater's southwestern rim.

Collecting KREEP-y samples

The Artemis III mission, which aims to put humans on the moon for the first time since 1972, is currently scheduled for mid-2027, following the completion of the Artemis II mission, which is due to launch at some point before the end of April 2026. The initial mission will send a crewed spacecraft to orbit the moon, similar to the uncrewed Artemis I spacecraft, which successfully circled the moon in late 2022.

The Artemis III astronauts will land near the moon's south pole in one of nine potential sites, most of which lie inside the KREEP splash zone surrounding SPA, according to NASA. If they land in the right place, this could give the team the chance to collect valuable KREEP samples.

However, there is some uncertainty about when Artemis III will actually launch.

Both Artemis II and Artemis III have already been delayed several times. Historically high cuts proposed to NASA's 2026 budget have also led some experts to predict further delays, which may end up handing China the advantage in the race to return humans to the moon.

China has also already acquired the first samples of the moon's far side, which were returned to Earth in June 2024 by the Chang'e 6 spacecraft, from inside the SPA basin. However, despite sharing the valuable lunar rocks with several other countries, NASA has not yet been allowed to anlayze these samples.

Moon quiz: What do you know about our nearest celestial neighbor?

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus