Science history: DART, humanity’s first-ever asteroid deflection mission, punches a space rock in the face — Sept. 26, 2022

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

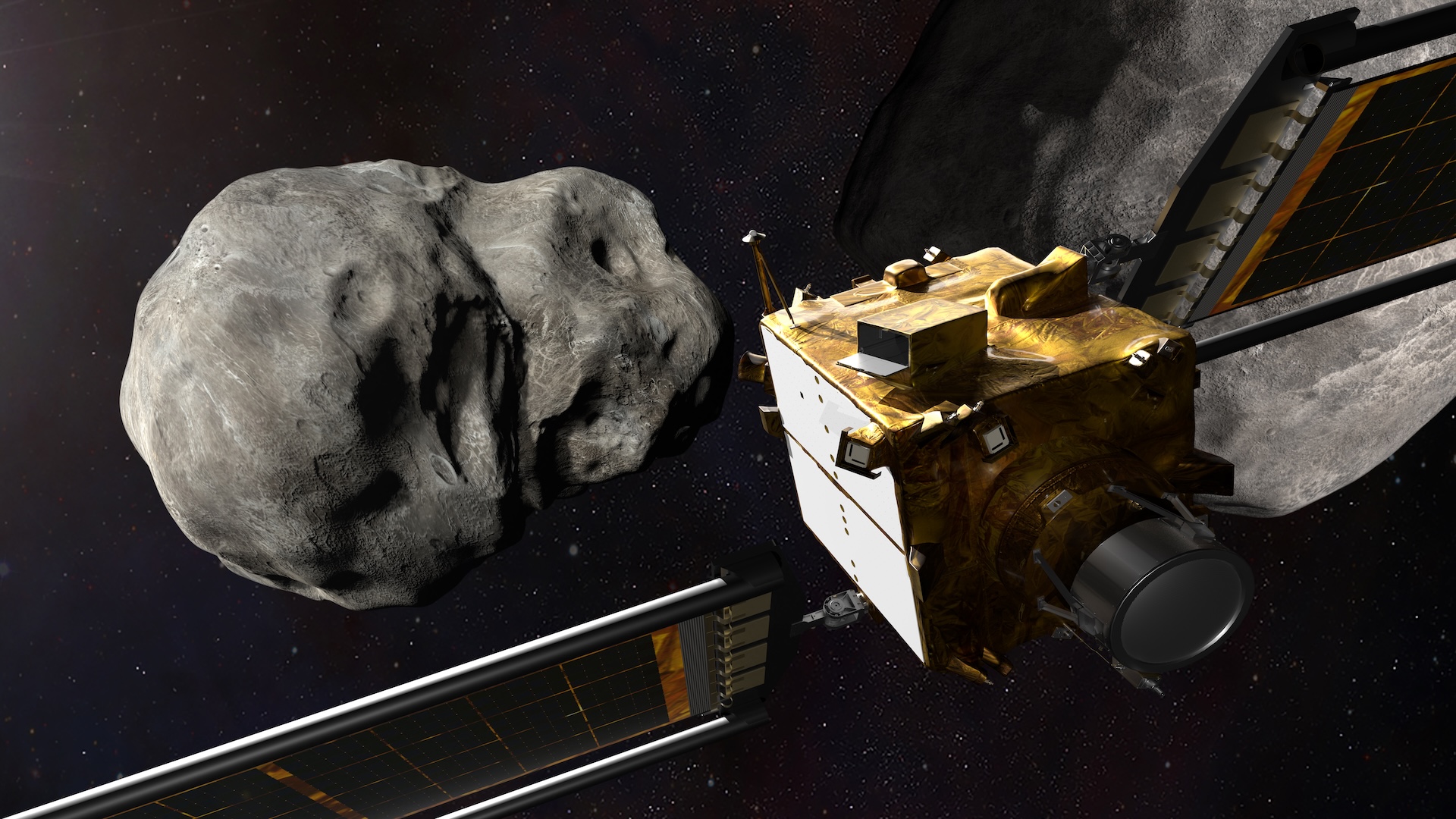

Milestone: DART rocket crashes into asteroid moonlet Dimorphos

Date: Sept. 26, 2022 at 7:14 p.m. EDT

Where: 11 million kilometers (6.8 million miles) from Earth

Who: NASA and Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory scientists

On Sept. 26, 2022, at 7:14 p.m. EDT, NASA smashed a pint-sized spacecraft into an asteroid — and changed the course of both the space rock and planetary defense forever.

The purpose of that mission, dubbed the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), was to see whether an "impactor," or a heavy, fast craft, could deflect a dangerous asteroid from a potential collision course with Earth.

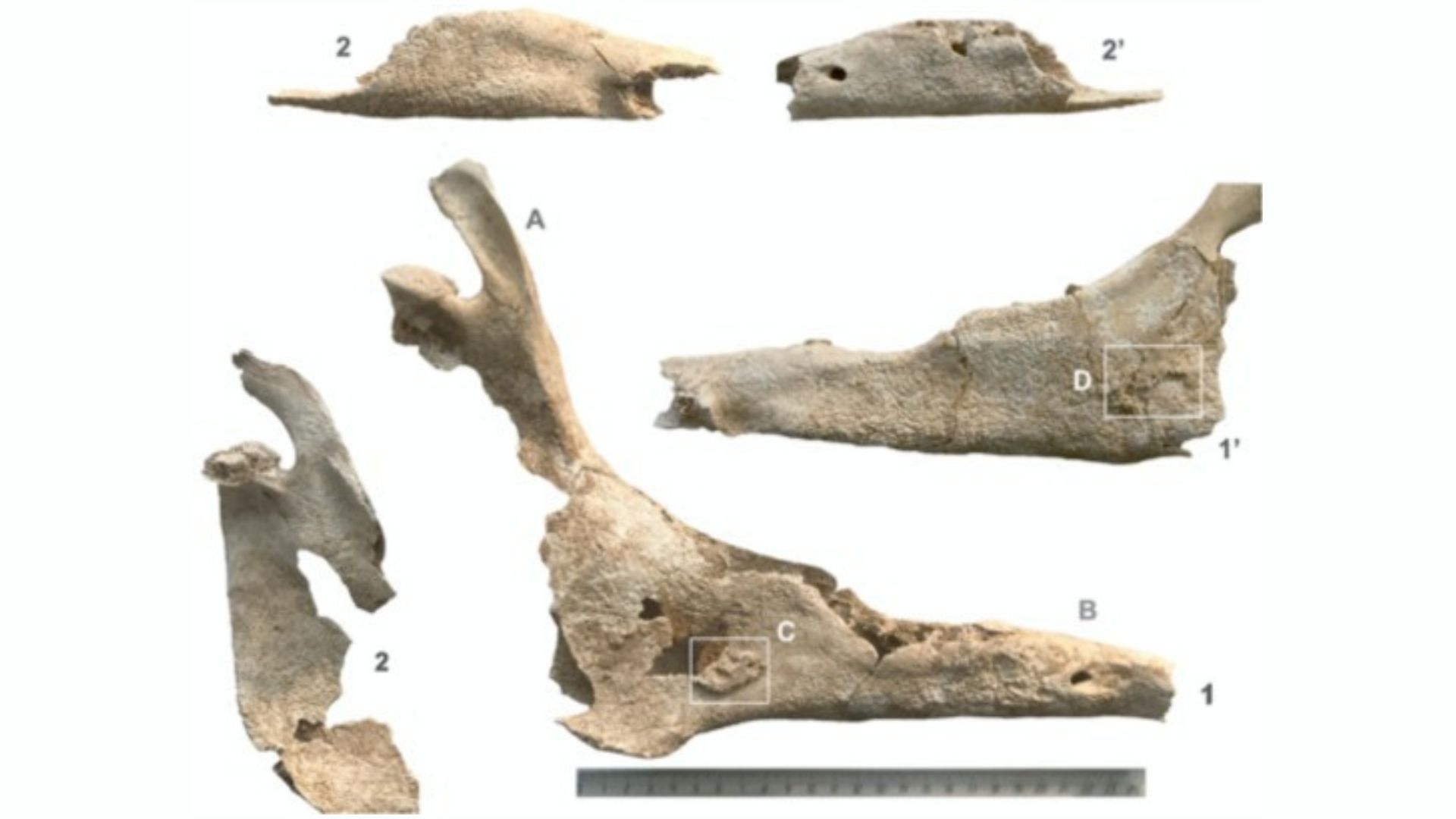

As early as 1968, students at MIT had proposed a thought experiment to commandeer NASA rockets to deflect an earthbound asteroid. But it wasn't till 1980, when geologist Luis Alvarez and colleagues found a global band of iridium in Earth's crust dating to the end of the Cretaceous period, that the potential stakes of such a strike became clear.

The layer of iridium, rare on Earth but common on asteroids, suggested that a massive space rock had struck our planet 66 million years ago, triggering a mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs. In 1992, scientists found the "smoking gun:" the roughly 120-mile-wide (200 kilometers) Chicxulub crater off of Mexico's Yucatan peninsula.

In the 1980s and 1990s astronomers identified a bevy of potentially dangerous space rocks — sometimes only after they had passed worryingly close to Earth. So they began to seriously consider proposals to neutralize asteroids: by nuking them , shooting lasers at them, shoving them off course with steam clouds, or smashing something big into them. (The “smashing” scenario is now known as the kinetic impactor method.)

Then in 2013, a meteor the size of a semitrailer breached the atmosphere over Chelyabinsk, Russia. Exploding with 30 times the energy of the Hiroshima blast, it blew out the windows on more than 7,000 buildings and caused instant ultraviolet burns and injuries to 1,600 people on the ground. No one saw it coming.

Chelyabinsk "was a cosmic wake-up call," then NASA Planetary Defense Officer Lindley Johnson said about the event.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2017, NASA approved funding for a project to test a kinetic impactor against Dimorphos, a moonlet that orbited the larger asteroid Didymos. The duo posed little threat to Earth, but because they skim relatively close to our planet, they presented a good test bed for the kinetic impactor method.

Over the next few years, scientists with NASA and Johns Hopkins' Applied Physics Laboratory built a 6.2-foot-long (1.9 meters), 1,280 pound (580 kilograms) spacecraft whose sole purpose was to slam into Dimorphos.

DART launched on Nov. 23, 2021, and smashed into the moonlet's rocky heart, just shy of center, on Sept. 26, 2022, using a special onboard camera to record its last moments. A tiny cube camera had split off from the main rocket days earlier, and lingered to record the chaotic aftermath of the collision.

DART shortened Dimorphos' orbit by 32 minutes, more than astronomers expected and far more than the 73 seconds needed for the project to be considered a success. The impact also created a swarm of boulders, Hubble revealed.

Follow-up studies have raised concerns about the unintended consequences of future deflection missions. One found that rogue boulders from the rubble pile could hit Earth and trigger a spectacular meteor shower in 30 years, while another study predicted that boulders could crash into Mars.

And earlier this year, scientists determined that the boulders aren't behaving as expected, traveling faster and in non-random configurations that hint at physics not yet accounted for. The findings suggest we still have more to learn before we can rely on such technology to save us from a true killer space rock.

"If an asteroid was tumbling toward us, and we knew we had to move it a specific amount to prevent it from hitting Earth, then all these subtleties become very, very important," Jessica Sunshine, a University of Maryland scientist who worked on DART, said at the time. "You can think of it as a cosmic pool game. We might miss the pocket if we don’t consider all the variables."

DART remains the first and only planetary defense mission to be tested on a real space rock. But China has announced that its space agency will mount its own DART-like mission to strike the roughly 100-foot-wide (30 meters) asteroid 2015 XF261, with the launch window opening as soon as 2027.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus