Fallout from NASA's asteroid-smashing DART mission could hit Earth — potentially triggering 1st human-caused meteor shower

A new study suggests that millions of tiny space rock fragments, which were ejected from the 2022 collision between asteroid Dimorphos and NASA's DART spacecraft, may be on a collision course with Earth and Mars.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Millions of tiny space rock fragments may be on a collision course with Earth and Mars after NASA deliberately crashed a probe into a far-away asteroid two years ago, a new study reveals. The celestial shrapnel, which could start hitting our planet within a decade, poses no risk to life on Earth — but it could trigger the first ever human-caused meteor showers.

On Sept. 26, 2022, NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft purposefully collided with the asteroid Dimorphos, smashing right into the middle of the space rock at around 15,000 mph (24,000 km/h). The epic impact, which occurred more than 7 million miles (11 million kilometers) from Earth, was the first test of humanity's capability to redirect potentially hazardous asteroids that pose a threat to our planet.

The mission was a major success. Not only did DART alter Dimorphos' trajectory — shortening its trip around its partner asteroid Didymos by around 30 minutes — it also completely changed the shape of the asteroid. It demonstrated that this type of action, known as the kinetic impactor method, was a potentially viable option for protecting our planet from dangerous space rocks.

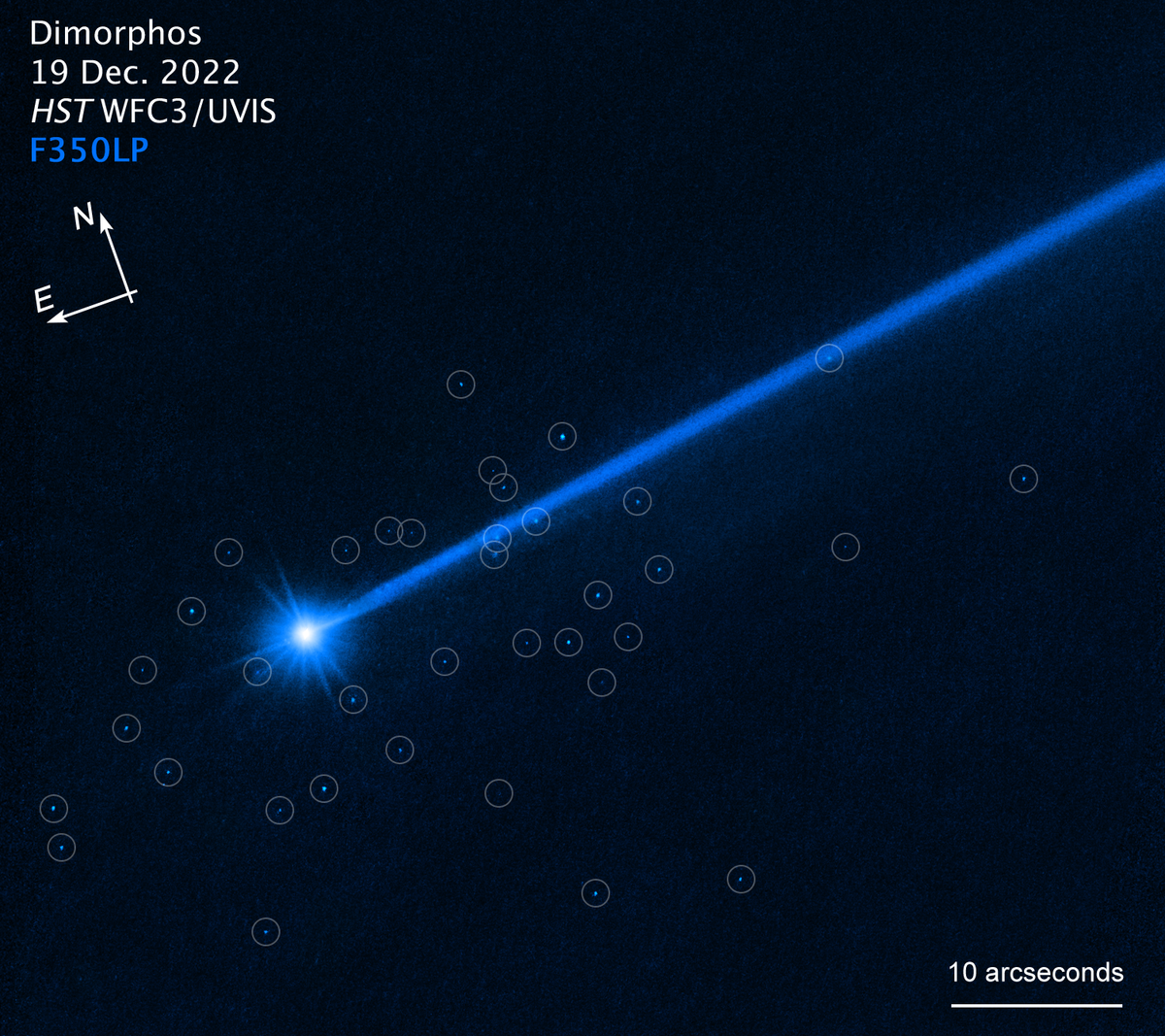

Photos of Dimorphos captured in the aftermath of the impact showed that the collision also ejected a large plume of debris into space, including dozens of large boulders that researchers believe could smash into Mars in the next few decades. None of these larger fragments are expected to hit Earth.

But in the new study, which was uploaded Aug. 7 to the preprint server arXiv and has been accepted for publication in The Planetary Science Journal, researchers turned their attention to Dimorphos' smaller fragments.

The researchers used a NASA supercomputer to analyze data collected by the European Space Agency's Light Italian Cubesat for Imaging of Asteroids (LICIACube) spacecraft, which flew alongside DART as the spacecraft smashed into Dimorphos. They then simulated the initial trajectory and velocities of 3 million fragments. This revealed that many of the asteroid pieces will likely reach Mars or the Earth-moon system.

Related: Could scientists stop a 'planet killer' asteroid from hitting Earth?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ejected fragments are harmless because of their diminutive size — between 0.001 inches (30 micrometers) and 4 inches (10 centimeters) across. But their arrival in Earth's atmosphere could trigger a new light show in the night sky.

"If these ejected Dimorphos fragments reach Earth, they will not pose any risk," study lead author Eloy Peña-Asensio, an aerospace engineer and astrophysicist at the Polytechnic Institute of Milan in Italy, told Universe Today. "Their small size and high speed will cause them to disintegrate in the atmosphere, creating a beautiful luminous streak in the sky."

However, there is still some uncertainty about when these fragments will reach us or when they will be visible.

The smallest fragments, which are likely traveling at speeds up to 3,350 mph (5,400 km/h), could reach us within seven years but will likely be too tiny to create any shooting stars in the sky, researchers wrote in the paper. But the larger fragments, which could be spotted as they burn up in the atmosphere, are moving more than four times slower and might not arrive for more than 30 years.

If and when these larger fragments arrive, they could create a brand new meteor shower, which the researchers have preemptively nicknamed the "Dimorphids." However, we won't know if this will really happen until these pieces start getting much closer to our planet.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus