An 'invisible threat': Swarm of hidden 'city killer' asteroids around Venus could one day collide with Earth, simulations show

A new study suggests that unidentified "co-orbital asteroids" around Venus may have the capacity to impact our planet in the future, with potentially devastating consequences. However, there is no immediate threat.

A hidden swarm of "city killer" space rocks, known as co-orbital asteroids, is likely hiding around Venus and could pose an "invisible threat" to Earth over the coming millennia if the asteroids are not found, new simulations suggest. However, there is no immediate danger to our planet, researchers told Live Science.

Co-orbital asteroids are space rocks that orbit the sun alongside a planet or other large body without truly orbiting the larger object. There are currently 20 known co-orbitals around Venus — ranging from "Trojan asteroids," which are fixed either in front of or behind a planet in its orbital plane, to a closely circling "quasimoon," known as Zoozve — all of which likely originated from the solar system's main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Dozens of similar co-orbitals also tag along with Earth, and more are being discovered all the time.

All of the Venusian space rocks are likely wider than 460 feet (140 meters) — large enough to be considered "city killers," meaning they could potentially wipe out a heavily populated area if they impacted our planet.

Although the co-orbitals pose no threat to us from afar, a close approach to Earth could cause them to be pulled away from their gravitational anchor — and thus put them on a collision course with our planet. Venus is one of our closest neighbors and comes closer to Earth than any other planet — within around 25 million miles (40 million km) at its nearest point — making its trailing asteroids a credible threat to our world.

Related: Undiscovered extra moons may orbit Earth. Could they help us become an interplanetary species?

Researchers think there are more hidden space rocks lurking around Venus. All but one of the planet's known co-orbitals have eccentricities greater than 0.38, meaning they have very elongated trajectories around the planet. This suggests there is an observational bias, likely because objects with lower eccentricities are probably being obscured by the sun's glare.

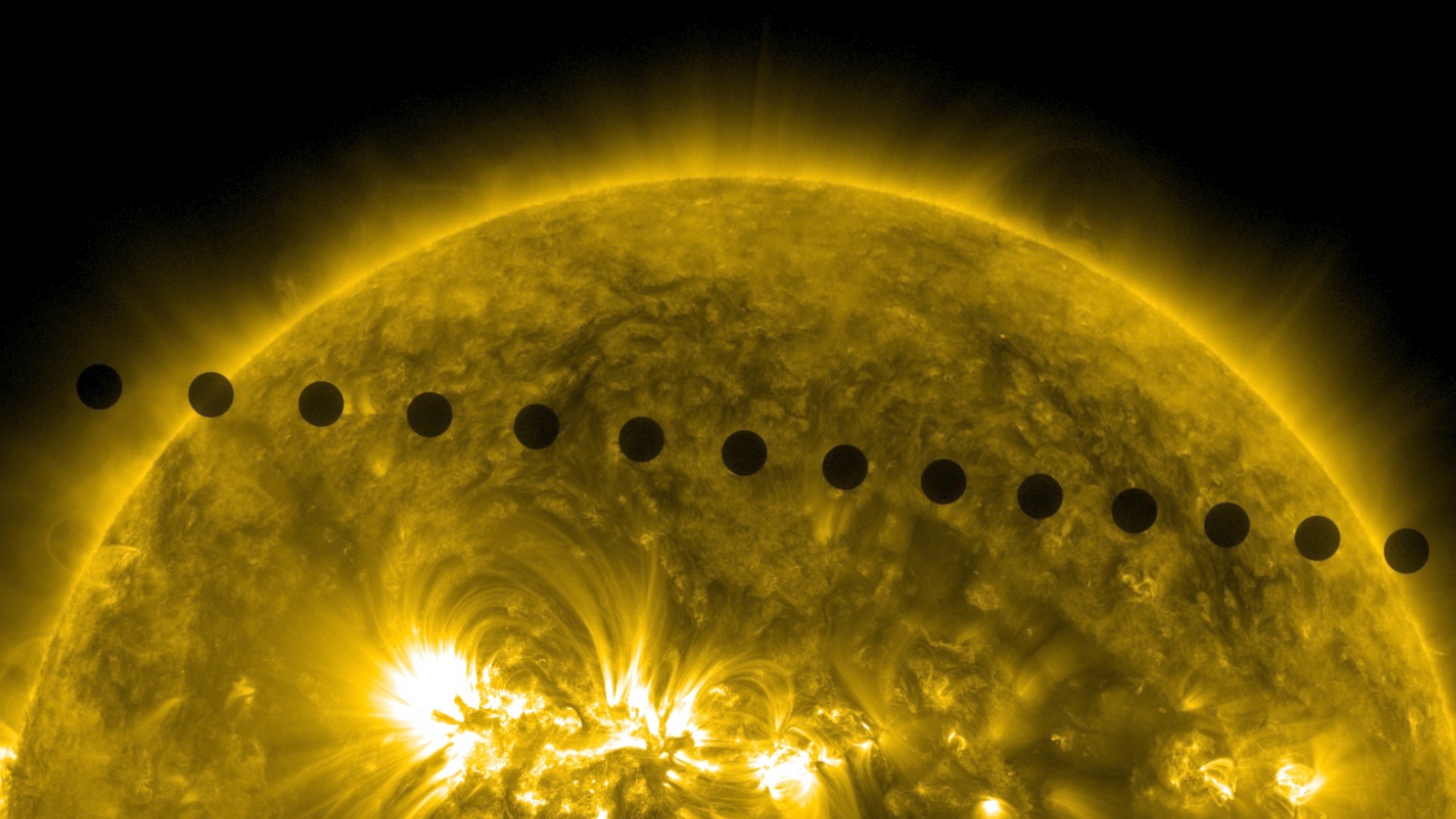

Co-orbitals can also move around relative to Venus, which can change their chances of colliding with Earth in the future. Previous research has shown that this likely happens to the space rocks once roughly every 12,000 years — known as a co-orbital cycle.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In a new study, which was uploaded May 21 to the preprint server arXiv and is currently undergoing peer review, researchers carried out a series of computer simulations to gauge whether hidden asteroids with lower eccentricities could threaten Earth. To do this, the researchers "cloned" known co-orbitals with eccentricities below 0.38 and simulated how they might behave over a 36,000-year period (three co-orbital cycles).

The simulations revealed that some of the newly added co-orbitals could pose a threat to Earth during this period. However, the study offers no indication of how likely a future collision really is, because it is "hard to predict" how many co-orbitals there really are, study lead author Valerio Carruba, an astronomer at São Paulo State University in Brazil, told Live Science in an email. "How many exactly is an open question."

"Exciting" asteroids

Since the new study was first uploaded, several media outlets have overhyped the risk of an imminent collision, with several tabloids claiming Earth could be hit by Venusian asteroids "within weeks." But there is nothing in the study to support those claims.

"None of the current co-orbital objects will impact Earth soon," Carruba clarified.

Carruba has been disappointed by some of the reporting surrounding the new study, but is glad the topic is being covered. "There has been some sensationalism about this research, and our work has been cited with some liberties," he said. "But we hope that this attention could raise interest in a very exciting class of asteroids, which should be more carefully monitored."

Related: 'Planet killer' asteroids are hiding in the sun's glare. Can we stop them in time?

The researchers also highlighted the recent discovery of the city killer asteroid 2024 YR4, which was initially predicted to have a 2.3% chance of colliding with Earth in 2032, before the odds were later downgraded to zero. This was an important reminder of the importance of detecting and monitoring potentially hazardous asteroids, they wrote.

New observational tools — such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, which will capture its first light later this year — will improve scientists' ability to spot dangerous space rocks, including Venus' co-orbitals, in the coming decades. However, it may also be prudent to send a telescope to Venus' orbit to specifically hunt for these objects, the researchers wrote.

"I believe that we should not underestimate their potential danger, but I would not lose sleep over this issue," Carruba said. "Soon, our understanding of this population will improve."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus