No, NASA hasn't warned of an impending asteroid strike in 2038. Here's what really happened.

Experts from NASA and other international organizations recently simulated their response to a hypothetical asteroid impact scenario. The test was deemed a success. However, several media outlets have misreported the group's findings.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Officials from NASA and other international organizations recently completed a mock test to assess their ability to respond to a hypothetical asteroid potentially crashing into Earth in 2038.

The tabletop exercise went as planned and has largely been deemed a success by those involved. However, several media outlets have misreported what happened, either making it seem like the impact scenario was real or that we are worryingly ill-equipped to deal with it — neither of which is true.

Between April 2 and April 3, nearly 100 experts from more than 25 organizations in the U.S. and abroad — including NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Department of State's Office of Space Affairs — met at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, to participate in the Planetary Defense Interagency Tabletop Exercise.

This event, which involved team members informally discussing potential responses to a hypothetical asteroid strike, was the fifth and largest version of its kind, following similar meetings in 2013, 2014, 2016 and 2022, Live Science's sister site Space.com reported.

"A large asteroid impact is potentially the only natural disaster humanity has the technology to predict years in advance and take action to prevent," Lindley Johnson, the lead program executive for NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office, said in a statement about the event. Simulating such a scenario can help give experts experience in dealing with such situations and highlight knowledge gaps in current protocols that need to be addressed in the future, he added.

Related: 'Planet killer' asteroids are hiding in the sun's glare. Can we stop them in time?

On June 20, leading members of the exercise team shared and discussed the results of the latest simulation in an online news conference. During this event, they also revealed the hypothetical scenario used in this year's exercise to the public for the first time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

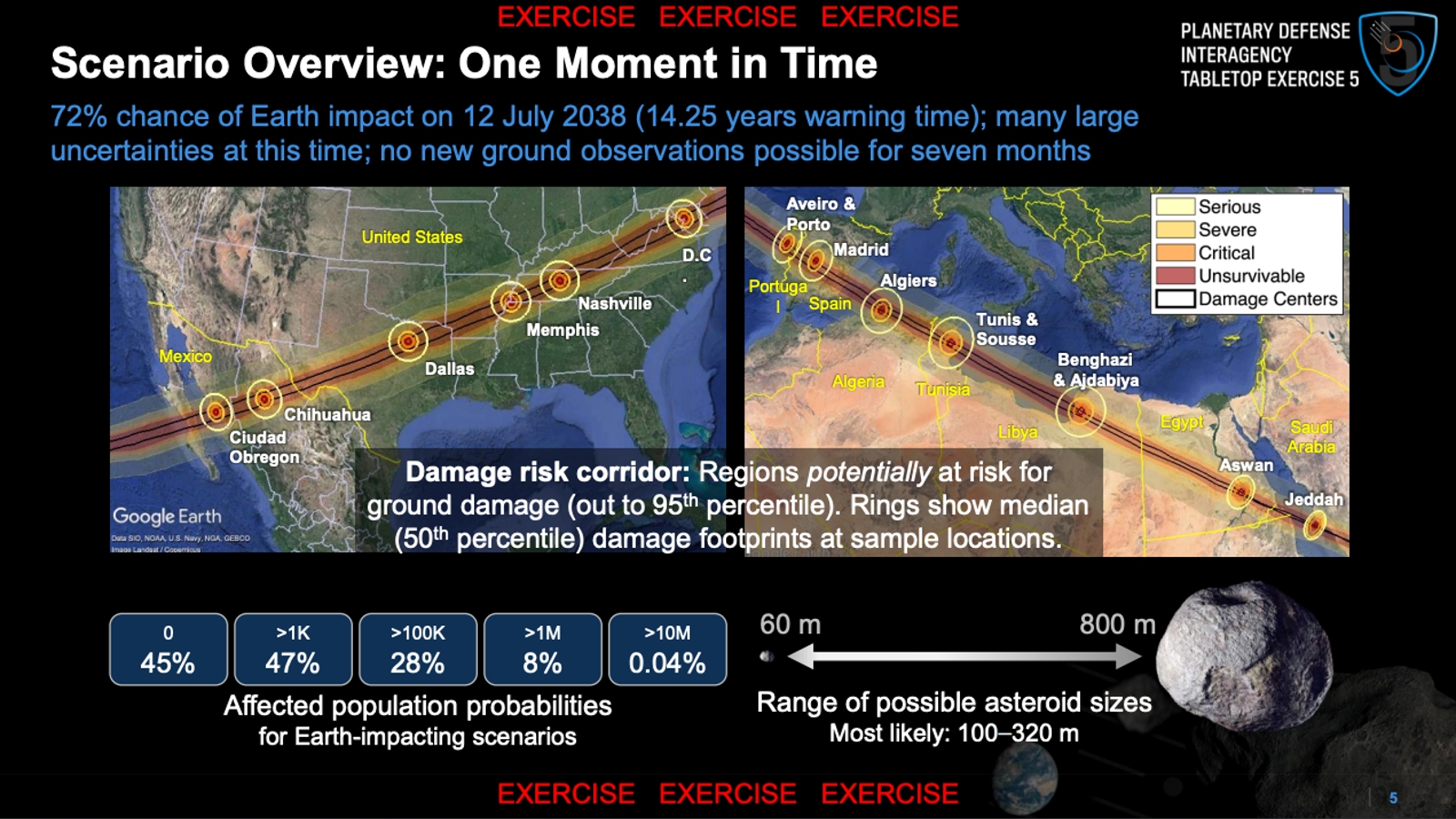

In the hypothetical new scenario, astronomers detect a large asteroid with a 72% chance of hitting Earth in 14 years — on July 12, 2038. Detailed information about this fictional asteroid is not immediately available, but its trajectory could put it on a collision course with major cities, including Dallas; Washington, D.C.; Madrid; and Algiers, Algeria. Uncertainty over the size of the space rock means that any potential impact could kill anywhere from 1,000 and 10 million people.

Some news outlets, including The Times of India and NDTV News, took this scenario out of context while reporting on the briefing. They used misleading headlines that suggested the threat laid out in the exercise was real and that NASA had "issued a warning" about the impending danger.

Other outlets — including the Daily Mail and The Register — suggested that the exercise showed we are poorly prepared to deal with this scenario in real life. However, these reports are also inaccurate.

Assessing the threat

This year's tabletop exercise presented a unique and "particularly challenging" scenario to the officials gathered in Maryland, Johnson said.

Despite having more time before the potential impact than in previous iterations of the exercise, experts had less information about the hypothetical incoming space rock than ever before. For example, they were told it could be anywhere between 200 and 2,600 feet (60 to 800 meters) wide. Also unclear was the asteroid's composition, which affects how destructive it would be.

To make matters worse, the scenario involved the asteroid disappearing behind the sun for seven months shortly after it was discovered, meaning the experts had to make plans without really knowing what was going to happen.

The team considered three options: first, wait for the asteroid to reappear for more observations; second, send a spacecraft to fly past the asteroid and learn more about it; and third, launch a mission to fly alongside the space rock, which would maximize the amount of information we could learn about it.

The consensus was to send a spacecraft to learn more about the asteroid rather than waiting to see what happens or launching a much more expensive rendezvous mission on short notice. However, the officials also raised concerns about our ability to do this, particularly because of how quickly such a mission would need to be put together and whether politicians would green-light the funding (up to $400 million) without more clarification about the situation. As a result, 19% of the participants said they thought we would be unready to plan and implement such a mission in this scenario.

Related: Could scientists stop a 'planet killer' asteroid from hitting Earth?

Some outlets latched on to this uncertainty, claiming that these potential hurdles would completely trip up our ability to deal with the asteroid. But in reality, most of the experts believed such a mission was feasible.

Because the tabletop exercise did not simulate anything beyond the initial decision-making stage after the asteroid was discovered, there is also no telling what would have happened afterward, which makes it impossible to label the event as a failure, as several outlets did.

Are we really ready?

In reality, we have never been in a better position to deal with scenarios like the one in the tabletop exercise, NASA representatives wrote.

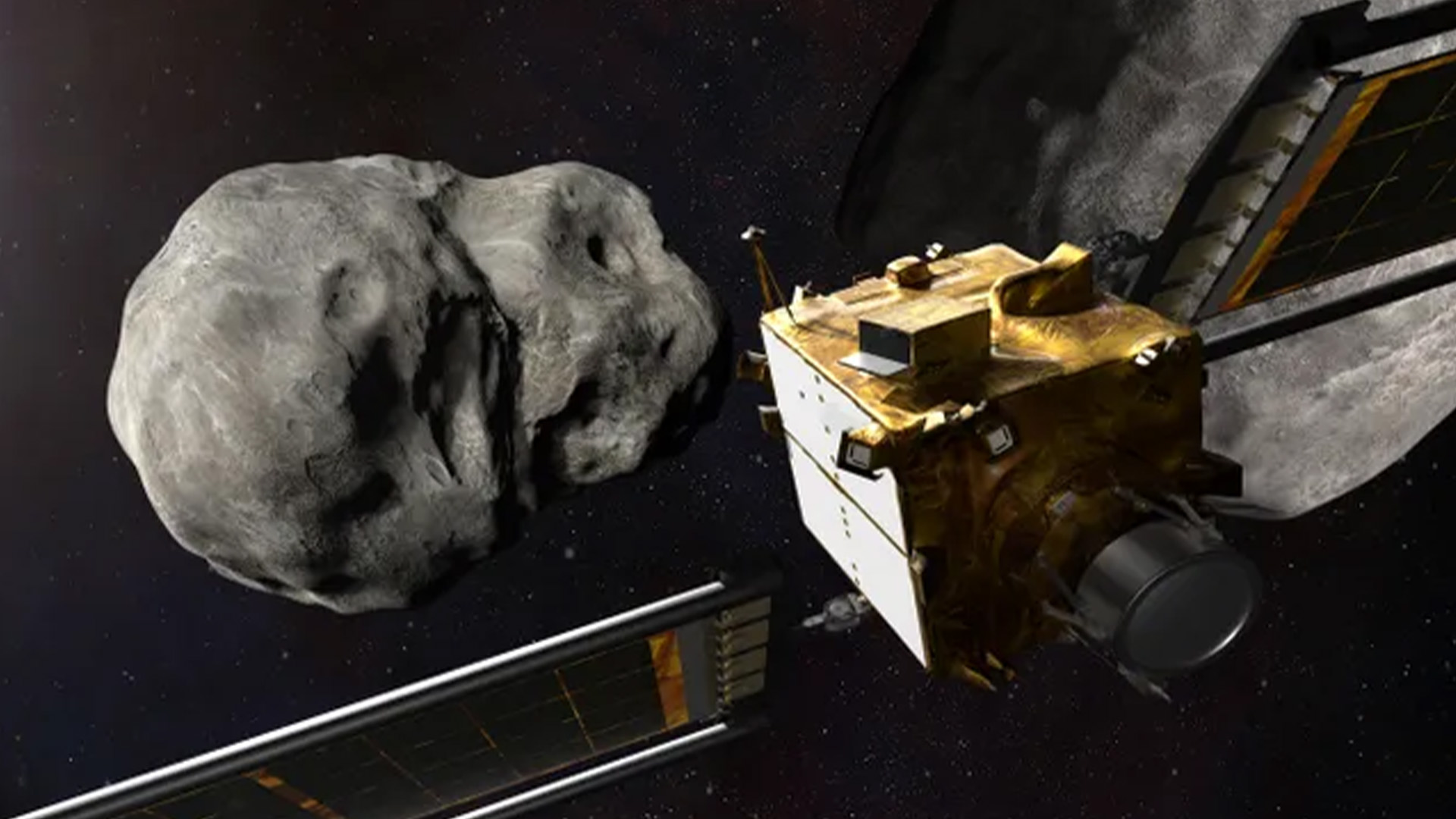

This is partially due to the recent triumph of NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, which successfully diverted and altered the shape of the asteroid Dimorphos after smashing a spacecraft into it on Sept. 26, 2022. Although it's not a perfect analogue for stopping a potentially deadly asteroid from hitting Earth (Dimorphos posed no threat to our planet), the test showed for the first time that the asteroid-deflection technique called the "kinetic impactor" method is a viable way of protecting our planet.

NASA also plans to launch the Near-Earth Object Surveyor — a space telescope dedicated to searching for new near-Earth asteroids — by the summer of 2028. Once in orbit, the telescope will increase our ability to spot dangerous space rocks, including those located close to the sun's glare, researchers wrote.

Continuing tabletop exercises like these will also help improve our readiness for a potential asteroid strike. For example, around 90% of the participants in the recent exercise said they felt more prepared to deal with the challenges raised in the exercise after it had concluded.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus