Moon is 40 million years older than we thought, tiny crystals from Apollo mission confirm

A new analysis of zircon crystals from the Apollo 17 mission has revealed that the moon formed around 40 million years earlier than past geological evidence suggested. However, our cosmic companion may be even older than that.

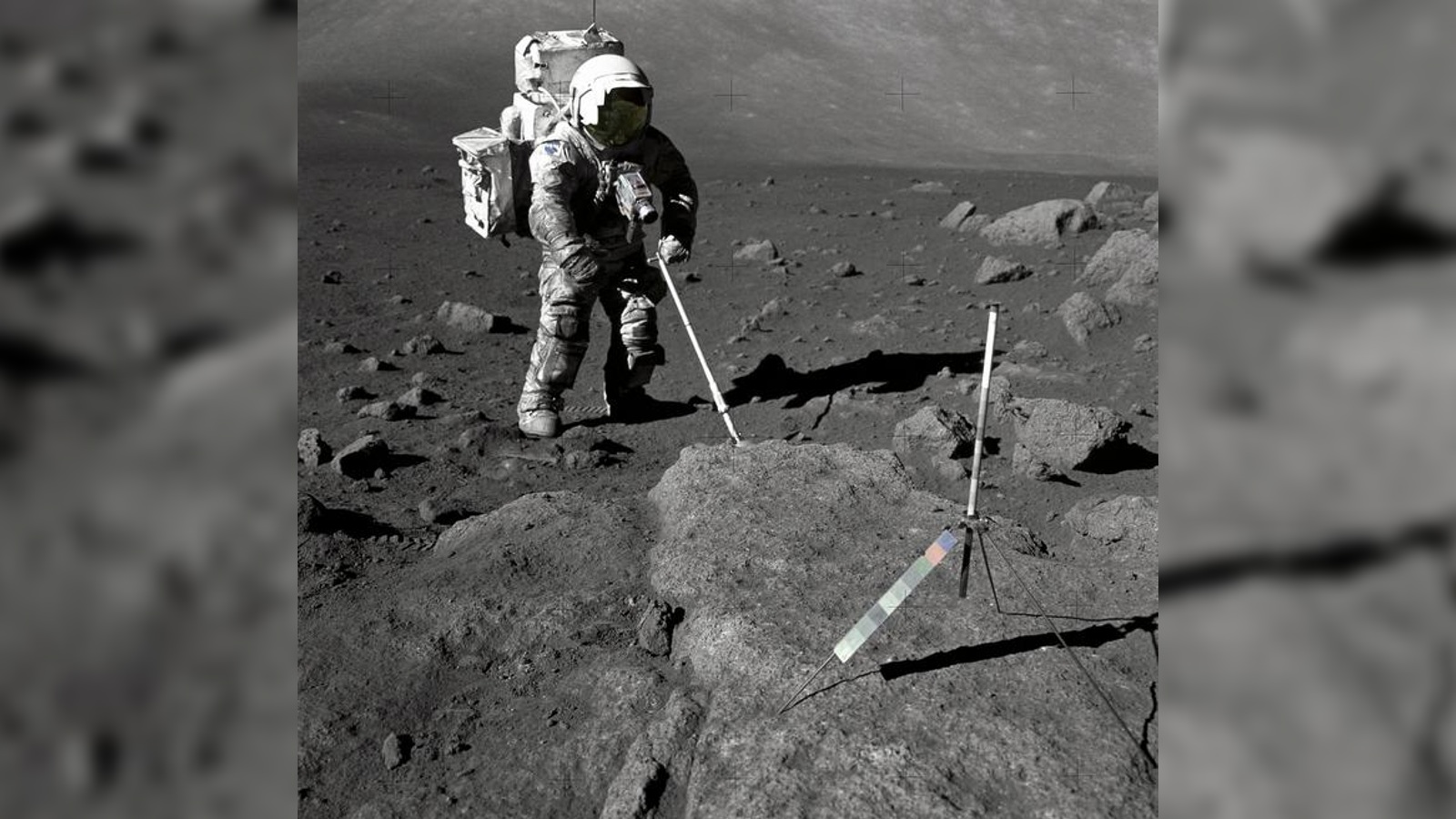

The moon is at least 40 million years older than we once thought, a new study reveals. Scientists confirmed our cosmic companion's new minimum age after reanalyzing tiny impact crystals from lunar samples taken by NASA's Apollo 17 mission in 1972.

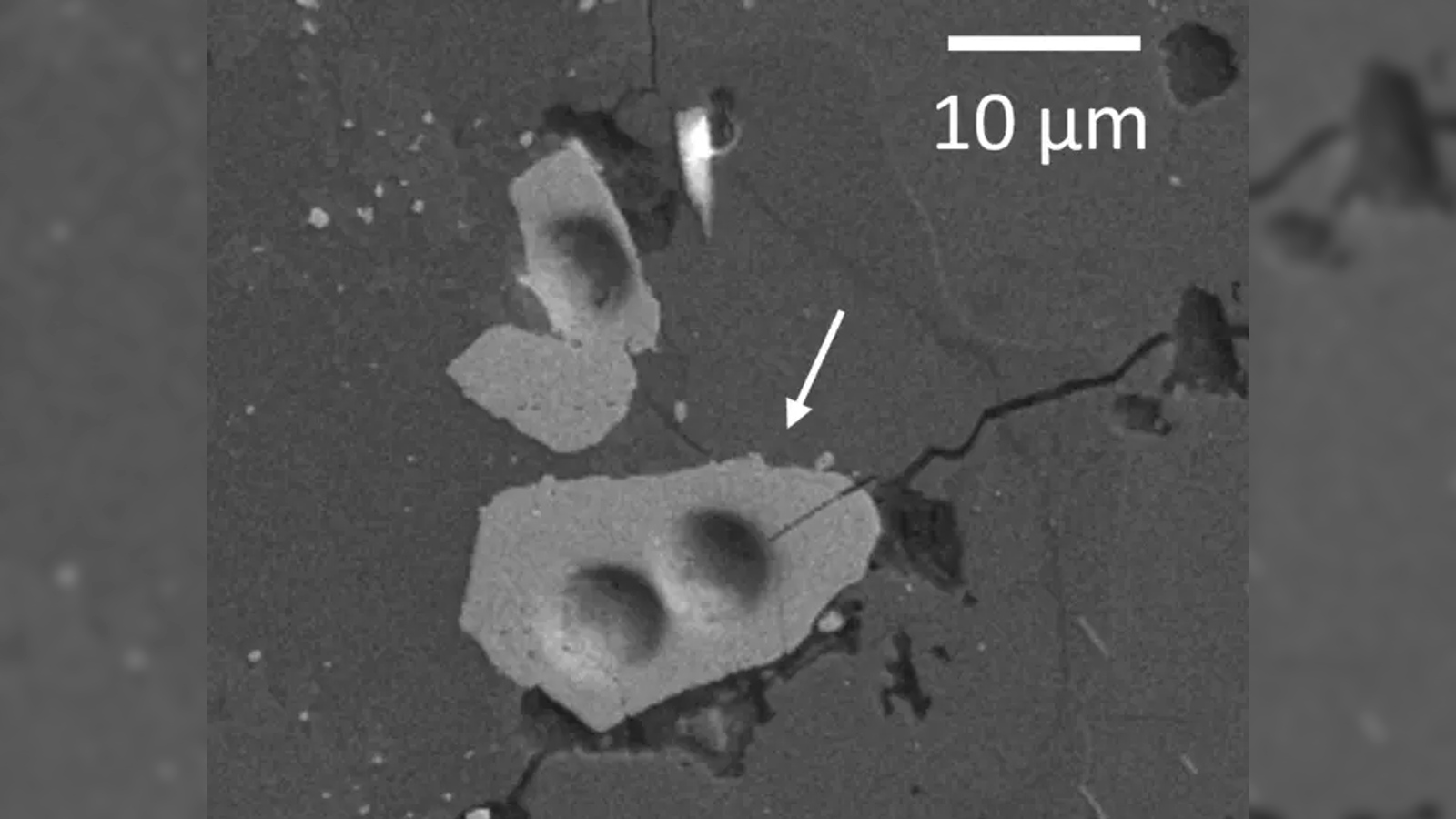

In a 2021 study, researchers first analyzed the lunar gems, known as zircon crystals — microscopic rocks created under intense heat and pressure that, on Earth, are used to date objects such as impact craters. The lunar grains were left behind when the moon formed following a colossal collision between Earth and a Mars-size planet, named Thea. The analysis, which involved measuring the decay rate of different versions, or isotopes, of uranium and lead in the crystals' outer layers, revealed that the samples could be up to 4.46 billion years old.

However, the 2021 study authors noted that there was a large amount of uncertainty in their dating method. As a result, the oldest confirmed lunar zircon crystals remained a group that was part of a separate Apollo 17 sample that was analyzed in a 2009 study, which put the moon's earliest possible birth date at around 4.42 billion years ago.

The new study, published Monday (Oct. 23) in the journal Geochemical Perspectives Letters, reanalyzed the crystals from the 2021 study, paying close attention to how the lead atoms clustered within the crystals. This confirmed that the crystals are indeed around 4.46 billion years old.

Related: 15 incredible images of Earth's moon

"These crystals are the oldest known solids that formed after the giant impact," study author Philipp Heck, a planetary scientist at the University of Chicago and director of research at the Field Museum, said in a statement. "And because we know how old these crystals are, they serve as an anchor for the lunar chronology."

Earth is approximately 4.54 billion years old. So based on the newest study, the zircon crystals were formed around 80 million years after our planet formed. However, the collision that birthed the moon could have actually happened even earlier.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After the Earth-Thea crash, the infant moon's surface would have been covered by a magma ocean due to the intense energy of the collision. Therefore, the lunar zircon crystals could only have properly solidified into their current state once the magma ocean had cooled down.

In a 2017 study, researchers created a computer model based on data from multiple lunar zircon samples to predict how long the magma cooling process may have taken and, as a result, when the collision actually took place. This revealed that the moon could be up to 4.51 billion years ago, Live Science's sister site Space.com reported.

Related: Will Earth ever lose its moon?

But although the 2017 study contains some "great work," the method used by the researchers was an "indirect approach" that lacked a "direct age determination," Heck told Live Science in an email. As a result, the newest study represents the best current estimate of the moon's age, he added.

Our understanding of the moon's history and geological evolution is constantly changing with new discoveries.

In July, researchers revealed that the "man in the moon" is 200 million years older than previously thought. And in November 2022, lunar samples collected by China's now-defunct Chang'e 5 rover revealed that volcanic eruptions occurred on the moon as recently as 2 billion years ago, which is around 1 billion years later than we realized.

Therefore, there is every chance that the moon's official birth date will be revised again at a later date.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus