Scientists scan famous 'Earthrise' crater on mission to find alien life in our solar system

A large lunar crater featured in the iconic 'Earthrise' photo has just helped the European JUICE spacecraft hone its alien-hunting instruments during a once-in-a-lifetime flyby.

A lunar crater immortalized in one of the most famous photographs ever taken has just played a key role in the hunt for alien life in our solar system.

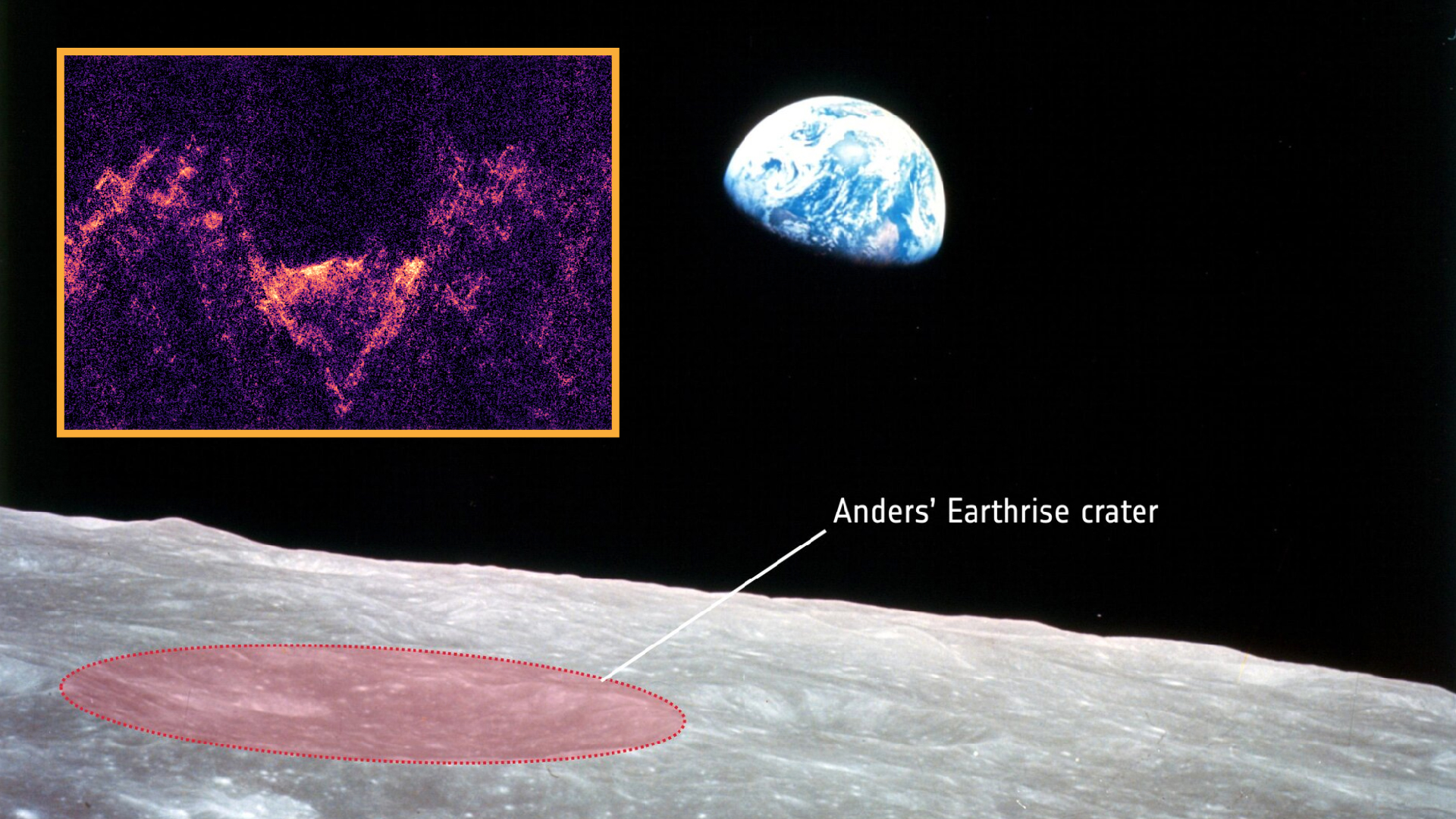

Stretching nearly 25 miles (40 kilometers) across the far side of the moon, the lunar impact crater formerly known as "Pasteur T" may be the most-viewed lunar crater in history. Countless Earthlings have seen it spreading prominently through the foreground of the iconic "Earthrise" photo snapped by American astronaut William Anders on Dec. 24, 1968, during the Apollo 8 mission. The majestic photo, which shows a half-lit Earth rising majestically above the lunar horizon, became so famous that the crater was renamed "Anders' Earthrise" in 2018.

Now, nearly 60 years after Anders' flyby put his eponymous crater on the map, another spacecraft has glimpsed it from orbit — this time, with extraterrestrial science in mind.

The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) spacecraft, which launched from Earth in April 2023 and is expected to reach Jupiter's orbit in 2031, flew past the moon nearly a year ago. Mission scientists used this encounter to test the spacecraft's 10 science instruments, which will eventually be used to hunt for signs of habitability on the many moons of Jupiter.

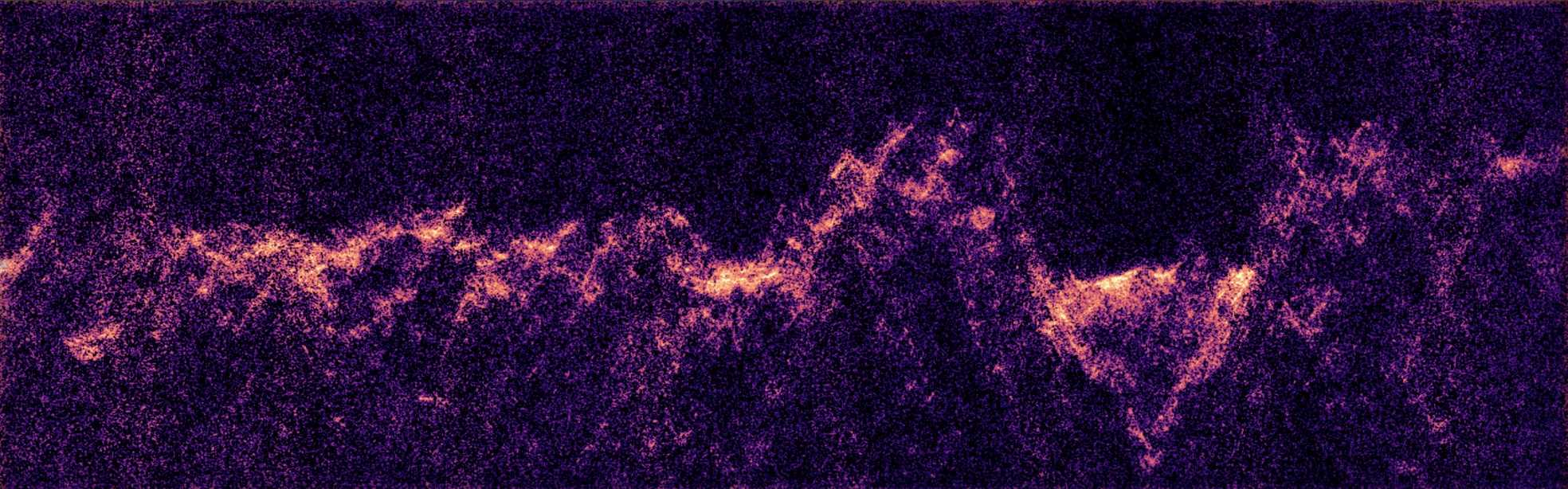

This lunar flyby presented the first opportunity to test the performance of JUICE's instruments on a solid surface in space, representatives from the European Space Agency (ESA) said in a statement. Of particular importance was the Radar for Icy Moon Exploration (RIME) instrument, which uses radio wave echoes to measure elevation on rocky bodies.

"RIME's task at Jupiter is to peer below the icy surfaces of moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto to map the invisible rocky layers below," ESA representatives wrote in the statement.

Related: 32 strange places scientists are looking for aliens

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because RIME needs to "listen" for precise changes in radio waves, the instrument requires as much silence as possible to get the best readings. That's where Anders' Earthrise crater comes into play. While JUICE sailed past the famous crater, ESA scientists silenced all of the probe's other instruments to let RIME observe it in peace for eight uninterrupted minutes.

RIME's radar mapped the moon's elevation in and around the crater, which researchers compared to earlier measurements taken by other spacecraft, such as NASA's Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA). The team found that electronic noise within JUICE was throwing off RIME's measurements — kicking off a months-long project to correct the issue with a new algorithm.

ESA now reports that this project was a success. The new elevation map of Anders' Earthrise crater (above) shows peaks and valleys that perfectly match the elevations captured by LOLA during earlier lunar flybys. The data prove that RIME is ready for its big job: charting the subsurface depths of the largest moons in the solar system — and, hopefully, aiding in the search for extraterrestrial life.

With a long journey still ahead, JUICE is now headed toward Venus, where our neighboring planet's gravity will give the spacecraft a boost on the path to Jupiter. Ultimately, JUICE will complete 35 flybys of Jupiter's most massive moons, before settling into orbit around Ganymede from December 2034 to September 2035, according to ESA. Studying Jupiter and its moons will not only provide new insights about the formation of gas giants and planetary systems at large but also help to tease out signs of life and habitability beneath the icy shells of the enormous moons.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus