Astronomers are racing to study our solar system's newest 'interstellar visitor.' Here's why.

Astronomers have been given the rare opportunity to study an extrasolar object after the recent discovery of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS. Experts tell Live Science how they are planning to observe the cosmic visitor.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The astronomical community is abuzz over a newly discovered "interstellar object," only the third of its kind ever seen, which is currently shooting toward us on a one-way trip through the solar system.

The race is now on to study the alien interloper, named 3I/ATLAS, before it leaves forever.

"We only have one shot at this object and then it's gone forever," Darryl Seligman, an astronomer at Michigan State University and the lead author of a new paper about the object, told Live Science. "So we want as much information from all of our observatories as we can possibly get."

Related: Watch newly discovered 'interstellar visitor' 3I/ATLAS shoot toward us in first livestream

Experts say studying 3I/ATLAS could potentially tell us about alien star systems and how exoplanets form — and we may even be able to trace it back to its origins.

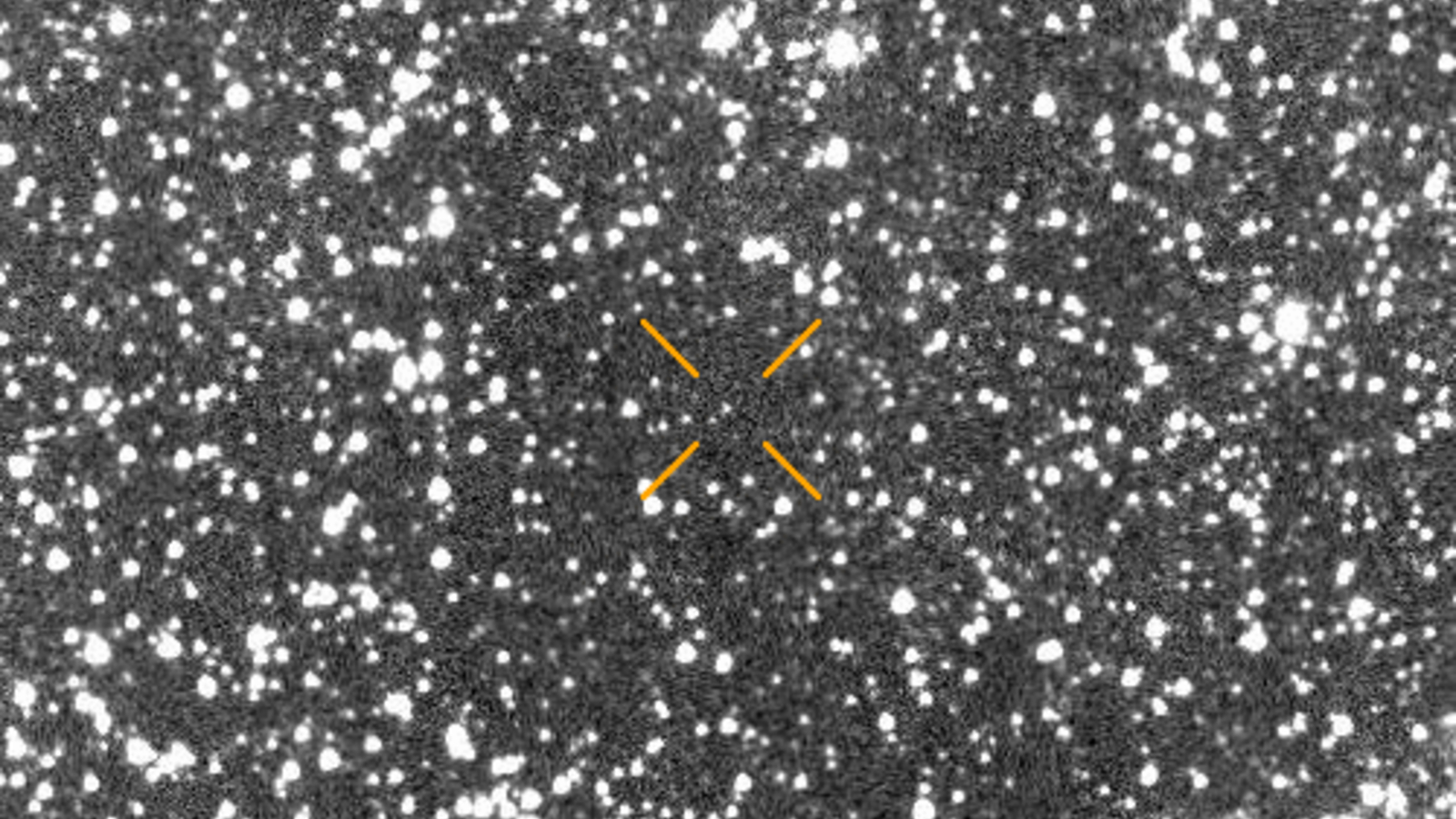

Initial discovery

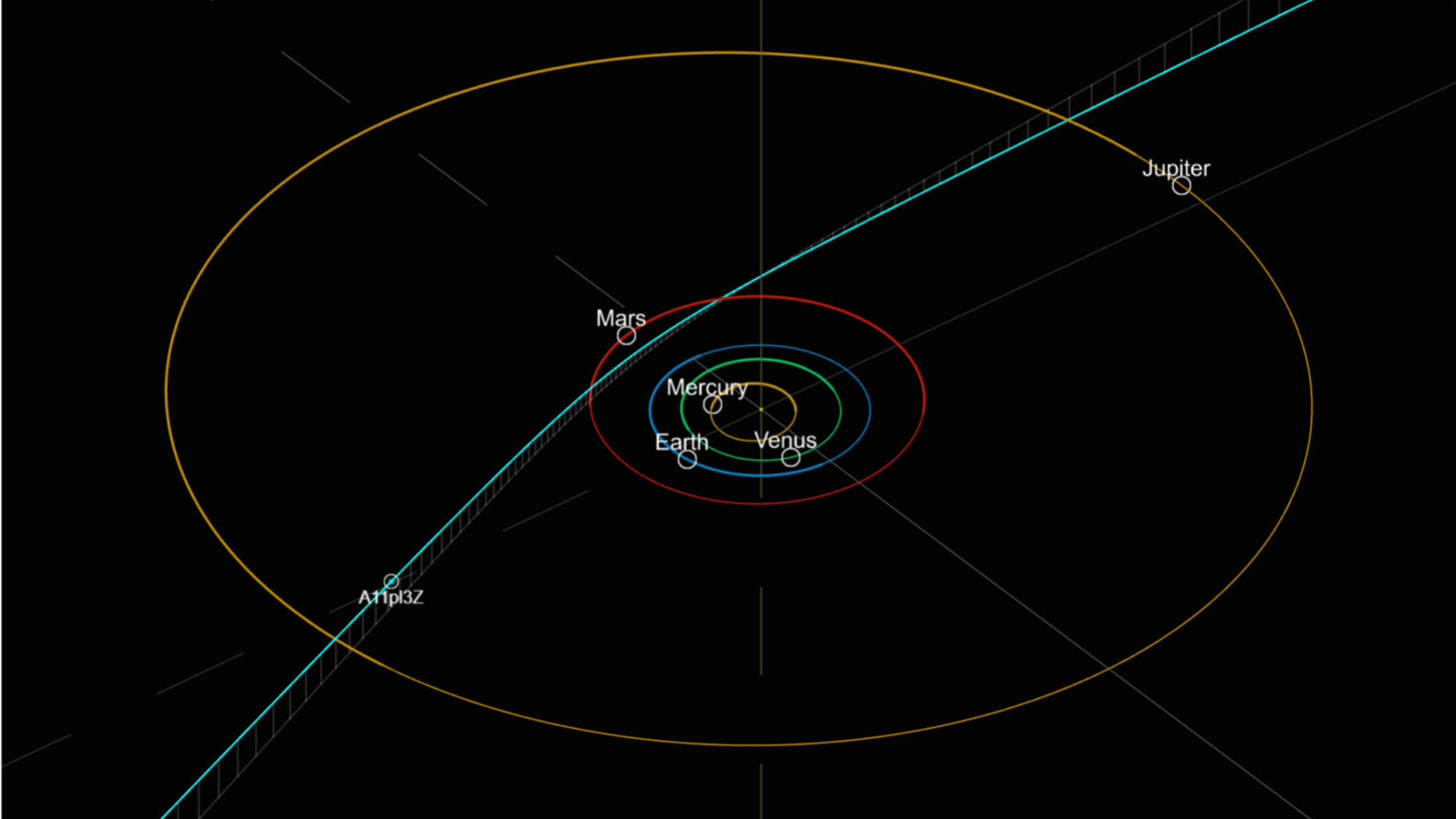

3I/ATLAS was discovered on July 1 from data collected by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) and immediately piqued researchers' interests due to its trajectory and extreme speed, which exceeds 130,000 mph (210,000 km/h). Within 24 hours of its discovery, NASA had confirmed that it was an interstellar object.

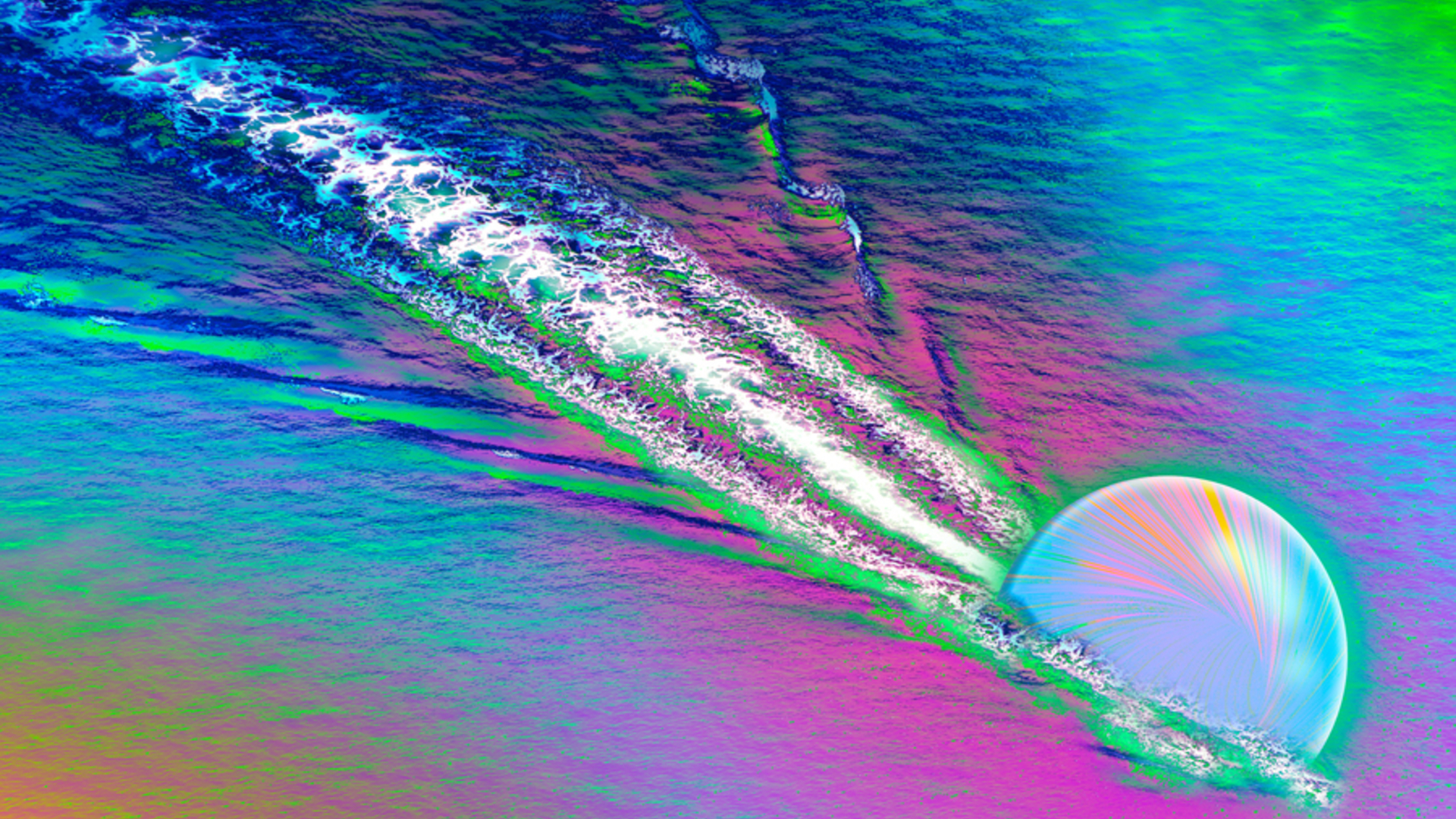

A day later (July 3), a group of more than 40 astronomers, led by Seligman, had uploaded the first paper describing the extrasolar entity to the preprint database arXiv. All data so far indicates that 3I/ATLAS is a large comet surrounded by a cloud of ice, dust and gas up to 15 miles (24 kilometers) across.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Prior to this discovery, only two other interstellar objects (ISOs) had been spotted: 1I/'Oumuamua, a space rock that was discovered in 2017; and 2I/Borisov, a comet spotted in 2019. This makes the newly discovered comet particularly appealing to astronomers.

However, there is a limited window to study 3I/ATLAS. The comet, which is currently around 4.5 times farther from the sun than Earth, will reach its closest point to the sun, or perihelion, on Oct. 30, before beginning its journey out of the solar system, when it will get much harder to spot. It will also be out of view between late September and early December, when it is positioned on the opposite side of the sun to Earth.

Observing an interstellar visitor

Over the next few weeks and months, researchers will attempt to use "any and all telescopes" they can to make observations of 3I/ATLAS, Sean Raymond, a planetary scientist at the University of Bordeaux in France, told Live Science in an email.

This will be especially true for observatories in the Southern Hemisphere, which will have a better view of the increasingly bright comet, Aster Taylor, a graduate student at the University of Michigan and co-author of the arXiv study, told Live Science in an email.

Experts are particularly excited about the possibility of imaging 3I/ATLAS with the Vera C. Rubin Observatory — the world's most powerful optical telescope, which recently released its first images. The observatory, located in Chile, has already proved to be adept at imaging never-before-seen asteroids and will undoubtedly target the interstellar comet when it comes fully online in a few months time.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and Hubble Space Telescope, meanwhile, could help reveal the interloper's chemical composition because of their ability to study the object in multiple wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum Pedro Bernardinelli, a planetary scientist at the University of Washington's DiRAC Institute, told Live Science in an email.

Some researchers have also proposed using NASA's Mars rovers to snap pictures of the comet as it makes a close pass by the Red Planet a few weeks before it reaches perihelion. The robots have previously been used to spy on dangerous sunspots lurking on the sun's far side from Earth.

Another intriguing option is to send a spacecraft to collect samples from 3I/ATLAS. However, the general consensus among experts is that such a mission is unlikely to happen

Alien star systems

Studying 3I/ATLAS provides a rare opportunity for us to glean insights into alien star systems and potential exoplanets.

"Interstellar objects are probably the leftovers of the formation of exoplanets," Raymond said. "Studying them can open a window into understanding other planetary systems' formation and evolution."

In this way, ISOs like 3I/ATLAS also "connects the solar system with its galactic environment," Amir Siraj, a doctoral candidate at Princeton University who has previously studied ISOs, told Live Science.

While it is still unclear where 3I/ATLAS came from, it's possible we can pinpoint its origins, especially if researchers can work out how old it is, Wes Fraser, an astronomer with National Research Council Canada, told Live Science in an email. And as the comet reaches perihelion, the amount of ice and other "volatile" substances that get burned off the interloper will help us narrow this down, Fraser added.

However, even then "we probably won't ever be able to pin it down to a single star system," Taylor argued.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus