NASA plans to build a giant radio telescope on the 'dark side' of the moon. Here's why.

A NASA-funded plan to build a large radio telescope on the moon's far side is nearing final approval and could become a reality by the 2030s, researchers say. The ambitious project will help safeguard astronomy from satellite "megaconstellations" — and help scientists unravel more of the radio spectrum.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

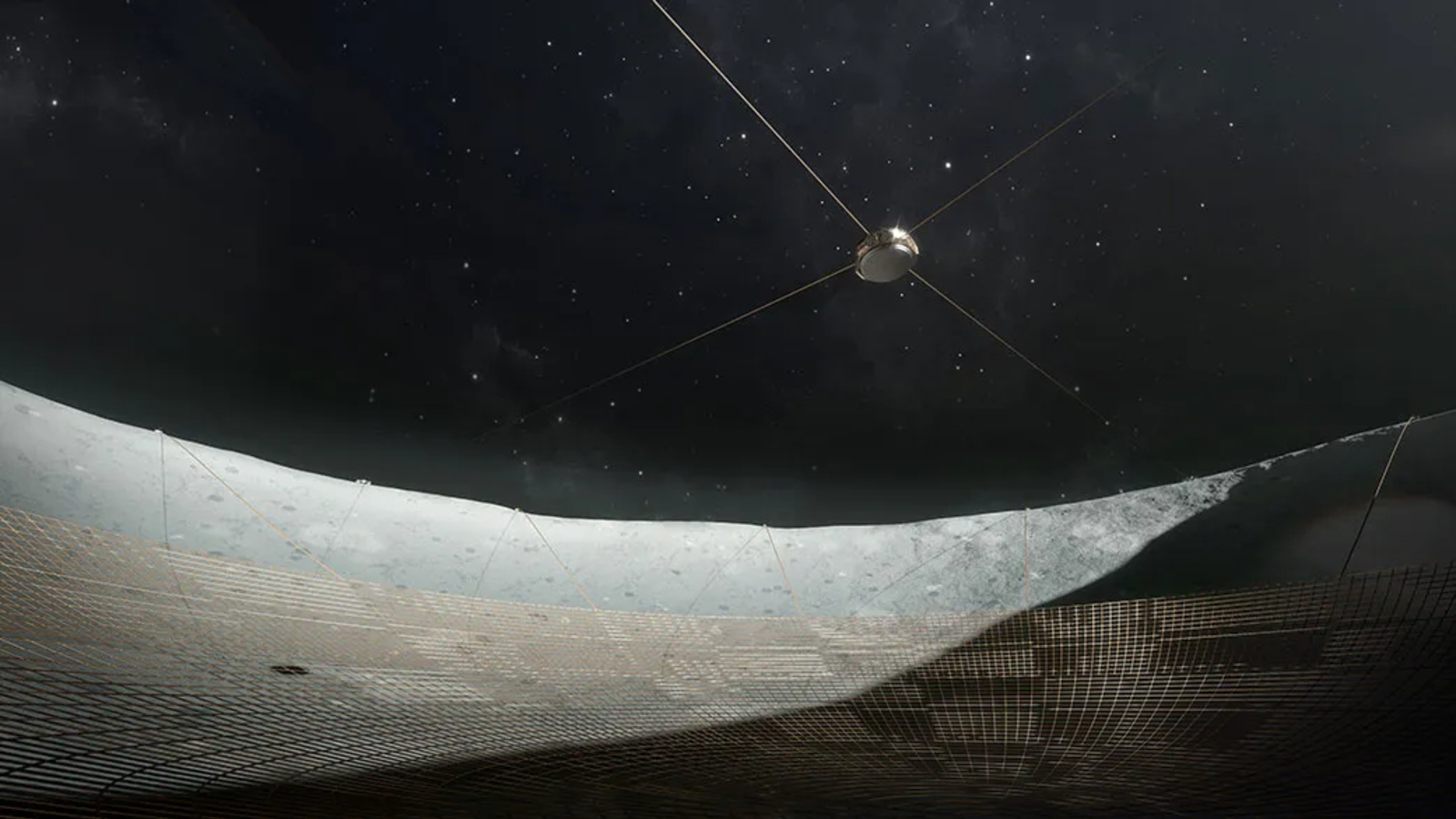

NASA scientists are currently working on plans to build a giant radio telescope in a nearly mile-wide crater on the "dark side" of the moon. If approved, it could be constructed as early as the 2030s and cost more than $2 billion, project scientists told Live Science.

Astronomers want to build the first-of-its-kind dish, known as the Lunar Crater Radio Telescope (LCRT), to help unravel some of the universe's biggest mysteries — but also because they are concerned about growing levels of invisible radiation leaking from private satellite "megaconstellations," which could soon disrupt Earth-based radio astronomy.

The proposed telescope will be built entirely by robots and consist of a giant wire mesh suspended via cables within a crater on the moon's far side, similar to the collapsed alien-hunting Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico or China's giant Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), which were both built within natural depressions on Earth. This will shelter the dish from satellite signals, as well as prevent interference from solar radiation and Earth's atmosphere.

The LCRT project is currently being investigated by a team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) at the California Institute of Technology. It was first proposed in 2020 and was awarded $125,000 in "phase I" funding from NASA's Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC). In 2021, the project reached "phase II" and was awarded an additional $500,000 of NIAC funding.

The team is preparing to apply for "phase III" funding, which could be granted as early as next year, and they are currently building a 200:1 scale prototype that will be tested at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory in California later this year, Gaurangi Gupta, a research scientist at JPL who is part of the LCRT project, told Live Science.

If the funding is approved — and the project passes this final phase — it will become a fully-fledged mission and the telescope could potentially be built at some point in the 2030s, Gupta said.

Related: Scientists may finally be close to explaining strange radio signals from beyond the Milky Way

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The most up-to-date plans for the telescope include a 1,150-foot-wide (350 meter) meshed reflector, which is larger than Arecibo's collapsed dish but smaller than FAST. This is around three times smaller than the 3,300-foot (1,000 m) reflector initially proposed in 2020, which would have been the largest single telescope ever built. The researchers have already selected their preferred crater — a 0.8-mile-wide (1.3 km) depression in the moon's Northern Hemisphere — but are keeping its exact location under wraps.

This is not the first time that scientists have proposed putting a radio telescope on the moon. The idea dates back to at least 1984, Gupta said. However, due to the technical challenges of building such a structure, it has never been seriously considered until now.

"But with state-of-the-art technology, LCRT can potentially solve all these issues and make this concept a reality," Gupta said.

However, the latest "rough estimate" suggests the construction of the LCRT could cost around $2.6 billion, Gupta said. This might prove to be the final stumbling block, especially as NASA's budget is being severely slashed by the Trump administration.

Safeguarding astronomy

The number of satellites orbiting Earth is rising fast, thanks to the emergence of private satellites, particularly SpaceX's rapidly growing Starlink constellation. This can create several problems, including an increase in space junk, rising light pollution in the night sky and a build-up of metal pollution in the upper atmosphere from satellite reentries.

A lesser-known issue is that private satellites are prone to accidentally leaking radiation into space, which can interfere with radio telescopes trying to study distant objects such as ancient galaxies, nearby exoplanets and supermassive black holes.

Several radio astronomers recently told Live Science that, if the number of satellites around our planet reaches maximum capacity, we could reach an "inflection point" beyond which radio astronomy would be extremely limited, and even impossible in some wavelengths.

If this were to happen, "it would mean that we are artificially closing ‘windows’ to observe our universe," Federico Di Vruno, an astronomer at the Square Kilometer Array Observatory and co-director of the International Astronomical Union's Center for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky, told Live Science.

Having a shielded telescope on the moon could allow radio astronomy to persist even if this worst-case scenario comes to pass. However, this one telescope would only allow us to do a fraction of the science currently being achieved by radio observatories across the globe, meaning our ability to study the cosmos would still be drastically limited.

Other researchers are also exploring the possibility of using a constellation of moon-orbiting satellites, as an accompaniment or alternative to the LCRT, Gupta said. However, these will likely have a much reduced window for observations than the larger telescope.

New wavelengths

In addition to preserving radio astronomy, LCRT could also allow us to scan wavelengths that Earth-based telescopes cannot.

Radio signals with wavelengths greater than 33 feet (10 m), known as ultra-long wavelengths, do not easily pass through Earth's atmosphere, making them almost impossible to study from the ground. But these wavelengths are also vital in studying the very beginning of the universe, known as the cosmic dark ages, because signals from this epoch have been extremely red-shifted, or stretched out, before they reach us.

"During this phase, the universe primarily consisted of neutral hydrogen, photons and dark matter, thus it serves as an excellent laboratory for testing our understanding of cosmology," Gupta said. "Observations of the dark ages have the potential to revolutionize physics and cosmology by improving our understanding of fundamental particle physics, dark matter, dark energy and cosmic inflation."

The LCRT would also be shielded from solar radiation, which can also interfere with some other radio signals, allowing those wavelengths to be more easily studied on the moon.

First attempts

If LCRT is approved it will be a major coup for science. But it will not actually be the first lunar radio telescope.

In February 2024, Intuitive Machine's Odysseus lander — the first private spacecraft to land on the moon and the first American lunar lander for more than 50 years — carried NASA's first Radiowave Observations on the Lunar Surface of the photo-Electron Sheath (ROLSES-1) instrument to the moon's near side. Despite the fact that the lander face-planted and ended up tilted on its side, the 30-pound (14 kilogram) telescope was still able to briefly collect the first lunar radio data.

However, because ROLSES-1 was facing Earth, almost all the signals it collected came from our own planet, offering little astronomical value, according to a study uploaded March 12 to the pre-print journal arXiv. "This is a good demonstration of why we need to be on the far side for reliable measurements of the dark ages signal in a radio-quiet environment," Gupta said

Later this year, Firefly Aerospace's Blue Ghost II lander will also attempt to land on the moon's far side. Among its scheduled payloads is the Lunar Surface Electromagnetics Experiment-Night (LuSEE Night) — a mini radio telescope from the U.S. Department of Energy that will scan the sky for ultra-long-wavelength signals, Live Science's sister site Space.com previously reported.

"The observations from these telescopes would be valuable for understanding the lunar environment, and the challenges and potential mitigation strategies to detect ultra-long wavelength signals," Gupta said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus