'I had never seen a skull like this before': Medieval Spanish knight who died in battle had a rare genetic condition, study finds

The extremely long skull of a medieval knight points to an underlying genetic condition.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

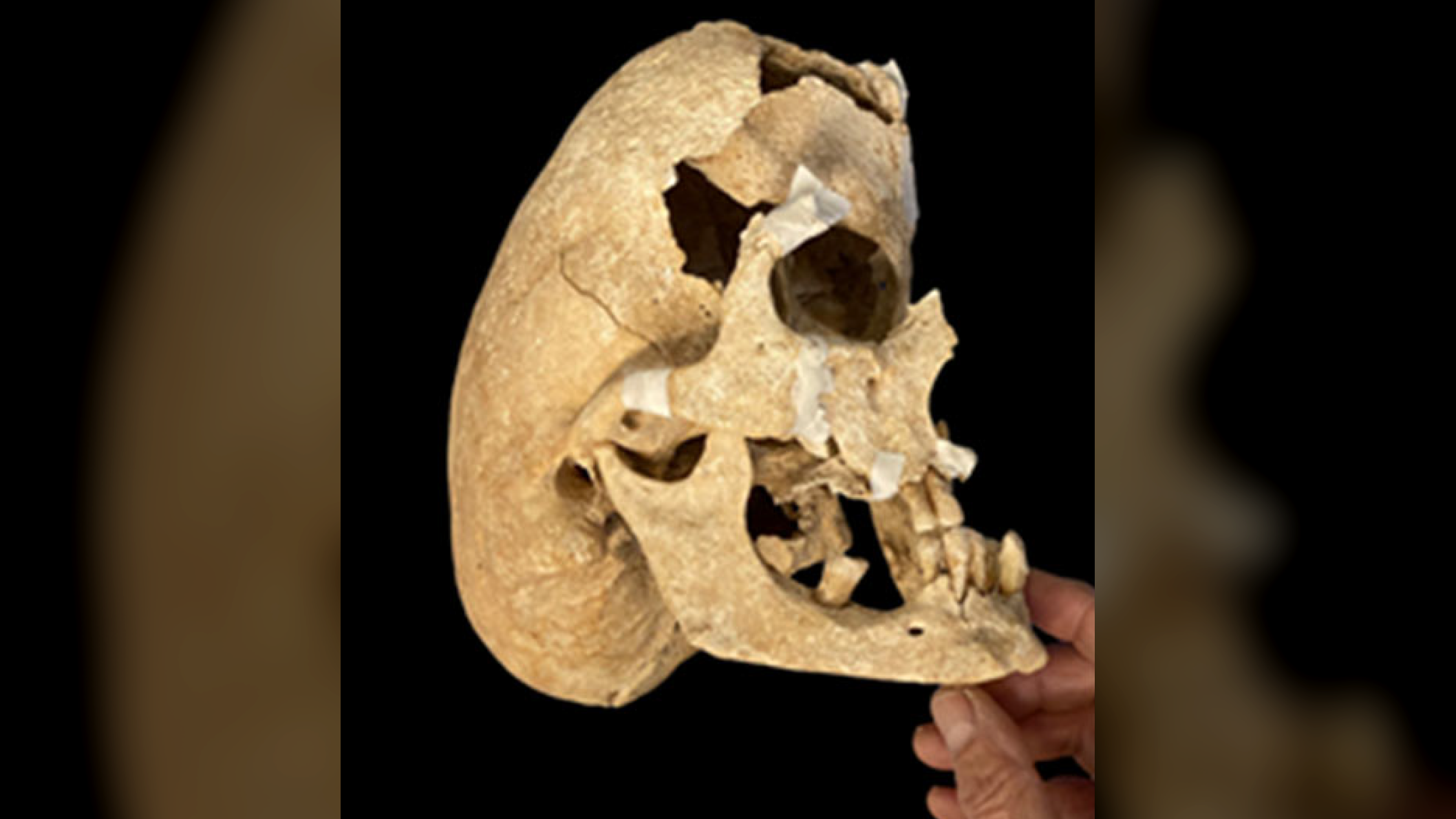

While excavating a cemetery full of medieval knights in Spain, archaeologists discovered the remains of a middle-aged man with two stab wounds on his head and a bashed-in knee, suggesting he died in battle. But when they took a closer look at the skeleton, they were shocked by his unusually long and narrow head, which they suspect resulted from a genetic condition that was typically fatal in childhood.

"I was very surprised," Carme Rissech, a biological anthropologist at the University of Rovira i Virgili in Spain, told Live Science in an email. "I had never seen a skull like this before, especially not one belonging to a knight."

In a study published Oct. 3 in the journal Heritage, Rissech and colleagues detailed their analysis of the bones of the skeleton, which was found at Zorita de los Canes castle in central Spain. The castle was occupied from the 13th to the 15th centuries by the Order of Calatrava, a group of knights and monks who took on military responsibilities.

When archaeologists excavated the Zorita de los Canes cemetery between 2014 and 2019, they uncovered dozens of human skeletons, including one of a woman, with traumatic injuries suggestive of violent incidents and battle wounds. But one individual stood out among the battered skeletons due to his "extremely elongated skull," the researchers wrote in the study.

The man had been buried in a wooden coffin that had largely disintegrated by the time it was excavated, and many of his bones had also decomposed over the centuries. A close study of his skeleton revealed he was in his mid- to late 40s when he died, and the muscle markers on his bones showed that he was an active person. But the researchers noticed that three of his cranial sutures — joints between skull bones — had closed prematurely, causing his head to be malformed.

When babies are born, their skull bones are basically small plates connected by fibrous joints called sutures. This flexibility lets the baby pass through the birth canal and allows the baby's brain room to grow. Most cranial sutures don't fuse together until a person is in their early 20s. If one or more sutures fuse too early — a condition called craniosynostosis — this can present problems for skull and brain growth. Today, surgery can be done to alleviate pressure on the brain caused by craniosynostosis, which can result in brain injury and death, but this sort of medical intervention was not available in medieval times.

The worldwide prevalence of craniosynostosis is about 1 in 2,500, according to the researchers, and many cases are the result of genetic mutations. One of the most common genetic mutations that causes multiple cranial sutures to fuse prematurely results in Crouzon syndrome, which can also cause wide-set, bulging eyes; a small jaw; and hearing loss. However, most people with this syndrome have normal cognitive function.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because only the medieval knight's skull was affected and the rest of his skeleton was not, the researchers think he may have had Crouzon syndrome — a rare find among archaeological skeletons.

"Most documented cases — particularly in the medieval period — are pediatric," the researchers wrote. "The survival of this individual into adulthood without surgical intervention is especially noteworthy, given the potential complications."

However, the researchers cautioned that further genetic analysis is needed to prove that the man had Crouzon syndrome.

Still, this medieval man clearly survived and thrived in spite of a potentially life-threatening genetic condition. His bones "exhibit signs of an active lifestyle, which could be consistent with that of a warrior," the researchers wrote, and the stab wounds to his head "suggest that he could have died in battle."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus