Giant sunspot that triggered recent solar 'superstorm' shot out nearly 1,000 flares and a secret X-rated explosion, record-breaking study reveals

The massive sunspot that sparked an "extreme" geomagnetic storm in May 2024 unleashed hundreds of other dangerous solar flares, including a hidden X-class outburst, a new paper reveals. The study sets a record for the longest continuous observation of a single active region on our home star.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A record-breaking study into a giant sunspot that triggered Earth's biggest geomagnetic storm in more than two decades has revealed surprising new details about the explosive dark patch. The monster sunspot unleashed almost 1,000 solar flares in just over three months, and may have discreetly birthed the most powerful outburst of the current solar cycle.

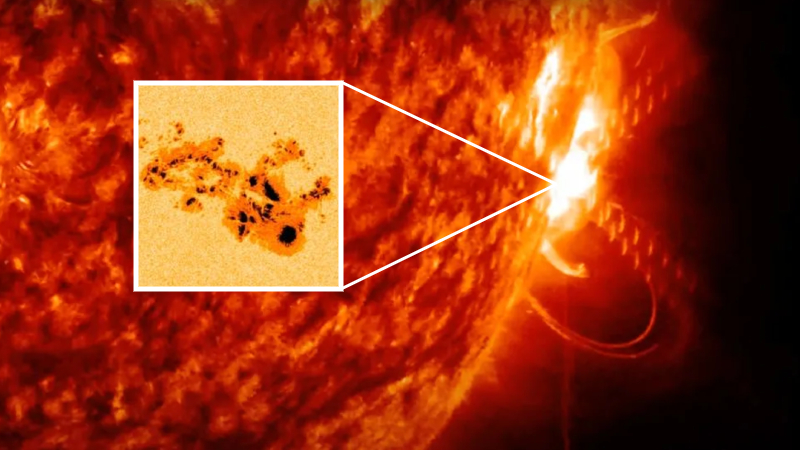

Back in April 2024, astronomers spotted a growing group of sunspots on the solar surface. This new active region (AR), dubbed AR 13664, quickly swelled in size, eventually reaching a diameter 15 times wider than Earth by early May. It then quickly unleashed a barrage of X-class solar flares — the most powerful type of solar explosion — that fired a series of coronal mass ejections (CMEs) toward Earth, which successively slammed into our planet's magnetic field.

This triggered a G5-level ("extreme") geomagnetic storm between May 10 and May 13, which was the most powerful of its kind since 2003 and painted widespread auroras around the globe.

But the giant sunspot's journey didn't end there. Like other massive sunspots, AR 13664 was able to survive several trips around the sun, which enabled researchers to keep tabs on it for longer than usual — and it put on quite the show. (Sunspots only remain visible on the sun's Earth-facing hemisphere for up to two weeks at a time before rotating out of view, but they reappear if they survive the trip across our home star's far side.)

In a new study published Dec. 5 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, researchers analyzed observations of AR 13664 spanning 94 consecutive days between April 16 and July 18, 2024, which equates to roughly 3.3 trips around the sun. Thanks to images captured by NASA's Solar Orbiter, which circles the sun, researchers were able to keep tabs on the sunspot as it rotated out of view.

"It’s a milestone in solar physics," study lead author Ioannis Kontogiannis, a solar physicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich), said in a statement. "This is the longest continuous series of images ever created for a single active region."

In the paper, the team revealed that AR 13664 unleashed a total of 969 solar flares. This included 38 X-class flares and 146 M-class flares, which are also capable of impacting Earth's magnetic field. The rest were lower-level, including C-class and B-class flares, which pose no threat to our planet. Most of the biggest flares were directed away from Earth, which is why more geomagnetic storms did not occur.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The largest flare was a suspected X16.5 magnitude blast, which occurred on the sun's far side from Earth on May 20, 2024. That’s significantly more powerful than an X9 blast that occurred on Oct. 3, 2024, which is currently listed as the most powerful flare of the last 8 years. However, as AR 13664's blast was partially obscured by its location on the sun, researchers cannot officially declare a new record.

AR 13664's epic journey around the sun is a reminder of the immense power of our home star, especially during solar maximum — the most active phase of the sun's roughly 11-year solar cycle, when the number of sunspots and solar storms sharply rises.

We have likely just finished the most recent solar maximum, which started in early 2024, much earlier than scientists initially predicted it would. This peak phase was also much more active than previous maxima, with a 23-year peak in visible sunspots and a record number of X-class flares in 2024.

The researchers behind the new study note that studying these events can help scientists to better predict similar events in the future, which is important as they can impact Earth-orbiting spacecraft as well as some ground-based infrastructure.

"We live with this star, so it's really important we observe it and try to understand how it works and how it affects our environment," Kontogiannis said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus